Thailand on edge for Yingluck trial verdict

- Published

Six years ago Yingluck Shinawatra, a novice who had only been in politics for two months, led the Pheu Thai party, founded and funded by her older brother Thaksin, to a resounding election victory.

It was a stunning result for a party which had seen two previous administrations overthrown by a coup and a controversial court decision, and whose supporters had just the year before been involved in an occupation of Bangkok, which ended in bloodshed.

An essential part of Ms Yingluck's winning manifesto was a generous promise to rice farmers. That is at the heart of the legal case against her.

Rice farming has always been central to the Thai economy and way of life

Under the new scheme the government was supposed to buy the entire rice crop, and pay 15,000 baht (£350; $450) per tonne, well above the 11,000 baht guaranteed by the previous government. It was wildly popular with farmers.

But economists and agricultural experts immediately questioned its viability. The price of 15,000 baht was significantly higher than the global rice price, and Thailand exports more of its crop than any other country - it was the world's number one rice exporter at the time.

Its principal rivals India and Vietnam, it was predicted, would simply increase their exports at Thailand's expense, offering a price much lower than the Thai government could, unless it was willing to incur huge losses. And there were many warnings that the scheme was vulnerable to corruption.

Wasteful and expensive

Six years later Ms Yingluck faces a possible 10-year prison sentence on charges of malfeasance, or dereliction of duty, over the rice scheme. She has not been charged with corruption, but with failing to prevent it, in her capacity as prime minister and as chair of the National Rice Policy Committee.

If convicted she could be permanently banned from politics - she has already been banned for five years after being impeached in 2015.

Yingluck Shinawatra was ousted by a military takeover in 2014

Unsurprisingly Ms Yingluck and her party have cried foul.

After all her government was overthrown, in 2014, by the same army officers who now run Thailand.

They justified their coup by the need to restore order, but had conspicuously failed to offer her support as she faced sustained protests in Bangkok, which had crippled her administration. The military is not seen as impartial, and it wields authoritarian powers, even extending to judicial cases.

The rice scheme was inordinately expensive and wasteful. The exact cost, of rice that rotted in storage, that was stolen or improperly sold, is still disputed. But the government estimates it cost the state at least $8bn - some estimates go as high as $20bn, although these include the overall cost of the subsidy, not just losses through corruption and mismanagement.

The scheme did raise farmers' living standards, but was almost certainly unsustainable.

There is plenty of anecdotal evidence of corruption, although few cases have yet gone to court. The best-known case, in which a former commerce minister and 27 other defendants are accused of an allegedly fraudulent government-to-government deal to sell rice to China, will conclude on the same day Ms Yingluck hears her verdict.

Ms Yingluck argued in court that she was not responsible for day-to-day running of the scheme, and that as a key policy platform when she was elected she could not order it to be cancelled. She pointed to what she believes are multiple procedural flaws in the case.

Ms Yingluck remains hugely popular and there are fears imprisonment could boost it further

Whatever the merits of the case against her, few observers doubt that the military government wants to see Thaksin Shinawatra's political movement weakened before it allows the restoration of some kind of democracy.

Ms Yingluck is very popular, and an effective vote-winner. With Mr Thaksin entering his 10th year of exile, his party is struggling to find a replacement leader.

But her fate presents Thailand's current rulers with some dilemmas.

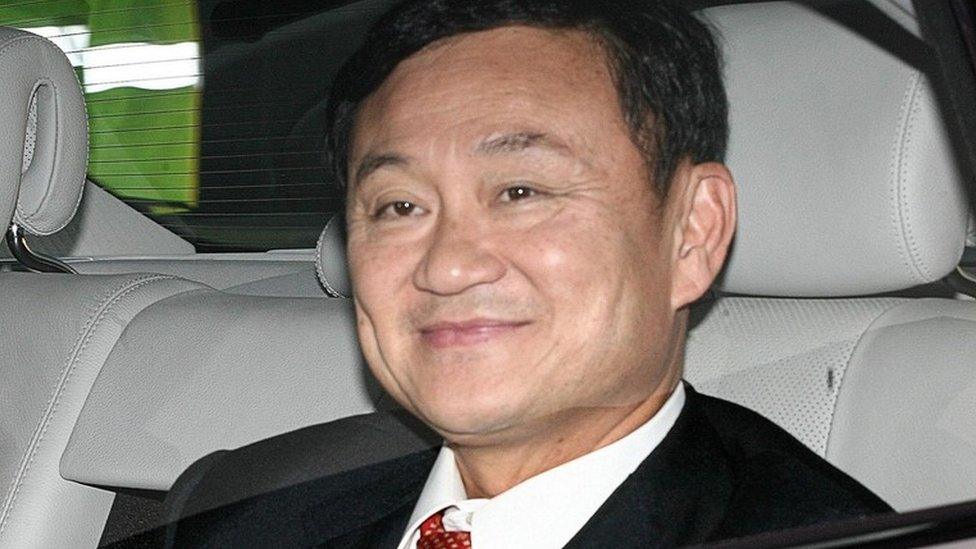

Thaksin Shinawatra has been living in self-imposed exile to avoid a jail term for corruption

If she is acquitted Mr Thaksin, who is protective of his younger sister, might be emboldened to push for a greater share of power in a post-election Thailand than the military is willing to accept. An acquittal would outrage hard-line conservatives, and those who led the protests against the Yingluck government.

If she is sent to prison, hard-line opponents of the Shinawatra clan would be satisfied, and she would be completely removed from politics. Convicting her would also help the generals to justify their coup, as part of a fight against corruption.

But it risks making the telegenic Ms Yingluck into a symbol of resistance for the so-called red-shirt mass movement that supports her.

Red-shirt leaders acknowledge that mobilising large-scale protests against a conviction would be difficult under a military government. They have ruled out any repeat of the occupation of central Bangkok that ended so badly seven years ago.

But they say they would view a conviction as the first shot in a re-ignited conflict with the military, as an end to any pretence of reconciliation. And they do not rule out localised demonstrations of anger by Ms Yingluck's supporters.

A lavish pyre is being built in Bangkok for the cremation ceremony for the beloved late king

This worries the government, because it wants calm in the run-up to the elaborate cremation of the late King Bhumibol Adulyadej in October. It will also need to be mindful of the wishes of King Vajiralongkorn, who is expected to hold a coronation ceremony not long after the cremation.

A possible compromise might be a suspended prison sentence for Ms Yingluck. This is possible if she receives less than five years. Even if she is given a custodial sentence, government legal experts say she can appeal. But that would depend on her. She might choose not to.

Behind all of this lies the jostling for a new balance of power once the generals allow an election to take place.

It remains unclear what involvement the new king will want to have in politics

In that election, polls suggest Pheu Thai will be the largest party, as it has been in every election since 2001, although the new electoral system will almost certainly ensure it does not win a majority of seats in the lower house of parliament.

But the political parties will have to contend with a 250-seat senate entirely appointed by the military, and with a military-drafted reform blueprint for the next 20 years, which all governments are legally required to honour.

In this environment no-one is sure who is in line to be the next prime minister. In the past in Thailand, elected governments were able to concentrate a lot of power and patronage in their hands. That will no longer be the case.

Some in Pheu Thai believe it might actually be better for the party to have a spell in opposition - that the first elected government will be so constrained by the courts and the generals it is not a prize worth having.

The military itself is factionalised, and it is not clear that the current ruling clique will remain dominant. Another important unknown is what King Vajiralongkorn wants.

The intimidating shadow of the lese majeste law makes any discussion of his role impossible in Thailand, but he has already made it clear that he wishes to be consulted on important decisions, and that he is willing to exercise his influence in ways that his father did not.

He may prove to be one of the most important factors in reshaping Thailand's future.

- Published23 August 2017

- Published6 October 2017

- Published1 December 2016

- Published3 May 2019