Thailand's political trial of the decade explained

- Published

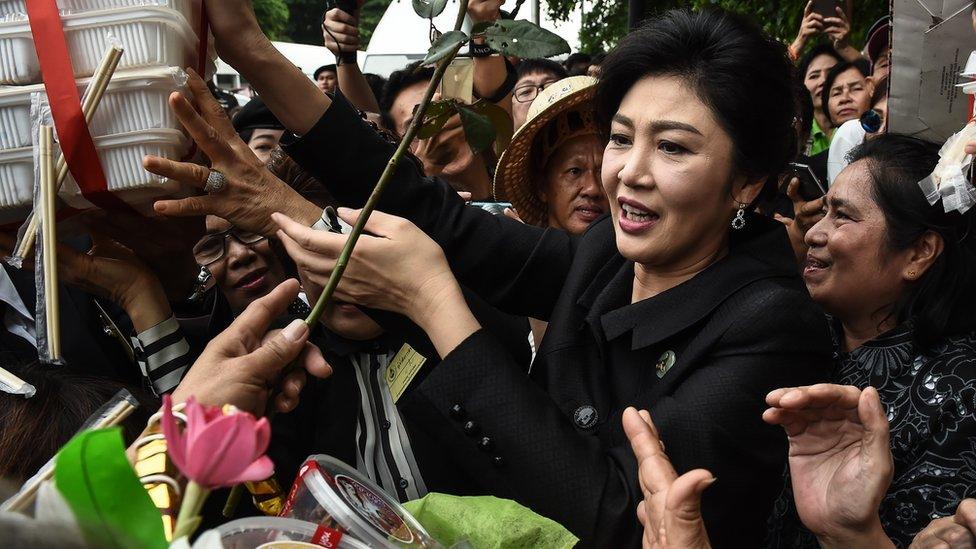

Yingluck Shinawatra was elected prime minister in 2011

In an unexpected development, Thailand's former Prime Minister Yingluck Shinawatra secretly left the country in late August just as she was due to appear for a verdict on criminal charges. She has now been sentenced in absentia to five years in jail.

The BBC's Jonathan Head in Bangkok answers some of the key questions around what's going on in the country.

Why was Ms Yingluck on trial?

The former prime minister was charged with negligence, essentially failing to prevent excessive losses and corruption in a rice subsidy scheme under her administration.

She faced up to 10 years in prison if found guilty.

Ms Yingluck's government was toppled by the military in 2014, and she was impeached over her role in the rice scheme a year later.

The former PM insists the case is politically motivated

Ms Yingluck was elected prime minister in 2011 and is the sister of former PM Thaksin Shinawatra, who was ousted by the military in 2006.

Like her brother, who remains a dominant influence over the Pheu Thai Party, she introduced populist policies which won her strong support in the mainly rural north and north-east. One of those policies was a scheme to buy farmers' rice crops for a generous price. The military government says it cost the state at least $8bn and was mired in corruption.

Our correspondent says it is impossible not to see a political dimension to the trial: "The military ousted her government in a coup and so the current rulers can hardly be considered impartial. And of course under a military government, there are always suspicions that the judiciary can be influenced.

"It is not surprising that Ms Yingluck and her supporters say the whole thing is entirely politically motivated."

Was her mystery-escape helped by the government?

Ms Yingluck had been widely expected to turn up in court on 25 August and her sudden disappearance caught her supporters and even some family members by surprise. For months, she had stood firm, refusing to leave the country, even though it is widely believed she was quietly encouraged to do so.

But Jonathan Head suggests her flight "will have been broadly welcomed in top circles, regardless of whether there was actual collusion or not".

"Looking at the way that Ms Yingluck got out of the country so quickly and at the last minute, to flee to Dubai, there's little doubt there must have been some high-level support for this."

Ms Yingluck still enjoys popular support

The government is denying any collusion but many people on all sides of the political spectrum in Thailand say it is hard to imagine she could have left unnoticed.

Why would the government allow her to leave?

Ahead of the trial, the military government was faced with a dilemma: whatever the verdict, it would likely have provoked an angry reaction from either of the two sides. Had she been acquitted, hardline opponents of Ms Yingluck would have been upset. Had she been given a prison sentence, her own supporters would have been equally angry.

Hence, many people think her fleeing is the best option for the government. "It takes the sting out of the possible verdict and reduces the possibility of an angry reaction," our correspondent explains.

"All this comes at a very sensitive time for the country," he says. "The cremation of the late King Bhumibol Adulyadej is scheduled for October, and the government wants there to be complete calm. It is a very important symbolic moment and carries a great deal of significance for the monarchy. The last thing that authorities want is any trouble."

What is the reaction among her supporters?

There was a sense of shock when her political followers found out out she had left the country.

Her Pheu Thai party has won every election since 2001 but now faces a problem: There is no one else in the family who could take the leadership role that she and before that her brother Thaksin had filled.

Yet the huge support base means the party will almost certainly remain the largest political force in the country.

What now for Thai democracy?

There's no other party in a position to replace Pheu Thai, our correspondent says. The party has an emotional hold over the north and north-east, making up about 40% of Thailand's voters. But the damage done to Pheu Thai may reduce its chances significantly of being able to form a government.

The new constitution, signed into law by the new king in April this year, already diminishes the power of elected parties. Under the new electoral system, it will be very difficult for Pheu Thai to win an outright majority as it has in the past.

Despite her strong support there's no expectation of unrest

So it is likely the previous dominance of Pheu Thai will be replaced by a more fractured political landscape, with the military and the traditional royalist elite playing a more influential role.

Will a guilty verdict lead to unrest and protests?

The fact that Ms Yingluck is out of the country takes away the symbol around which her supporters could rally.

"Thailand has been divided and polarised for the best part of the past 12 years," Jonathan Head says. "The military and the conservatives have not been able to destroy the Shinawatra family and the family has not been able to fight its way back into a position of dominance they once had.

"The general assumption has been that in the end either one side has to be destroyed, or there has to be a grand bargain. The latter scenario doesn't seem to be viable at the moment, but at the same time it is not clear if the current situation represents the beginning of the final destruction of the Shinawatra family's influence."

- Published26 August 2017

- Published25 August 2017