Risky road: China's missionaries follow Beijing west

- Published

When so-called Islamic State announced on 8 June that it had killed a Chinese man and woman in their mid-twenties in Pakistan's most volatile province, many would have assumed they were two of the thousands of workers that Beijing has sent to the country in the last few years.

China is investing more than $55bn (£43bn) in Pakistan, a key beneficiary of its grand plan to connect Asia and Europe with a new Silk Road paid for by Beijing.

Such an ambitious project involves risk, and China is building major infrastructure projects in Balochistan, a Pakistani province home to a long-running separatist insurgency and an array of militant and jihadist groups.

But Meng Lisi and Li Xinheng were not there to work on Chinese-funded projects.

They were in the provincial capital, Quetta, on a clandestine mission: to spread the word of Christianity in the unlikeliest and most dangerous of places in conservative Muslim Pakistan.

Their story draws attention to an unintended and often overlooked by-product of China's aggressive drive to develop new trading routes and carve out influence across Asia, Africa and the Middle East.

Hundreds and possibly even thousands of the country's growing cadre of Christian missionaries are along for the ride too - even if Beijing doesn't want them there.

'Why didn't they save our children?'

The province of Zhejiang, on China's eastern coast, is one of the country's Christian centres.

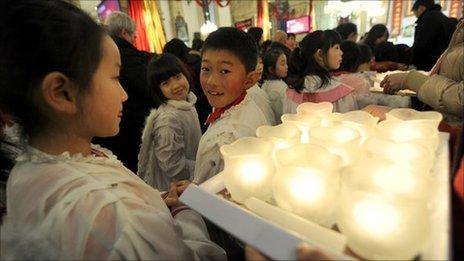

There are thousands of protestant churches here, both official ones permitted by the atheist Chinese Communist Party and so-called "underground" or "home" churches, whose members often meet private homes.

Neither of the pair who ended up in Quetta were originally from Zhejiang, but they did join home churches in the province.

Millions of Chinese Christians worship in "underground churches", like this one in Beijing

Meng Lisi, 26, was originally from Hubei while Li Xinheng, 24, was from Hunan.

Mr Li's mother, who only wanted to be named as Mrs Liu, said her son did not know Ms Meng before he travelled to Pakistan in September 2016.

She says she thought he was going there to teach Mandarin, but quickly adds that as a Christian she would be "proud" if it was true that he was proselytising there.

After armed men masquerading as policemen kidnapped the pair in Quetta on 24 May, the Pakistani military launched a three-day operation in a region south of the city called Mastung, targeting fighters allegedly linked to IS.

It is in Mastung that IS later said it had carried out the killings, and Mrs Liu questions why the Pakistani government launched an attack in the area instead of trying to negotiate their release.

"Why didn't the Chinese government tell the Pakistan side to save our children?" she asks.

The car Meng Lisi and Li Xinheng were kidnapped in

Mrs Liu says her phone is monitored, and authorities have been investigating the family. The leader of her local protestant home church, meanwhile, has "blacklisted" her.

Since the young missionaries were killed, the Chinese authorities have repeatedly said they are continuing to investigate in response to queries from journalists.

Why Chinese Christians have turned to underground churches

But the government has responded with a crackdown at home, detaining at least four preachers from church groups in Zhejiang as part of a targeted blitz against house churches connected to overseas missions, says Bob Fu, whose US-based China Aid group supports Christians in the country.

They have been released but are not allowed to continue their activities and are banned from giving media interviews, he says.

There are likely more Christians in China than Communist Party members

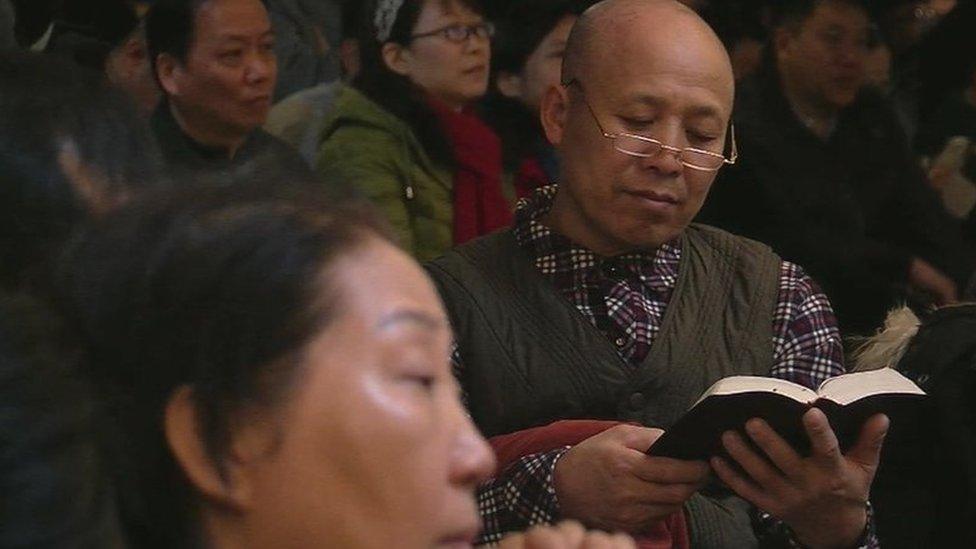

China's up to 100m Christians have been subject to increased scrutiny and harassment since Xi Jinping became president in 2012, Mr Fu says, adding: "He has been worse than any leader since Chairman Mao".

Crosses were torn down from more than 1,000 churches in Zhejiang between 2014 and 2016.

Dismay as church crosses removed in China

But incidents like the killings in Pakistan present a tricky dilemma for Chinese authorities. As a self-declared atheist government, news of Chinese Christian missionaries getting into trouble abroad is embarrassing. But at the same time, Beijing needs to show it can protect its citizens as it goes global.

As Fenggang Yang, an expert on religion in China at Purdue University, puts it: "They thought Christianity was a western religion imported into China, so how can you export Christianity from China?"

"This is new and the Chinese authorities are still struggling to figure out what to do with this."

'They said we were all sinners'

When Meng Lisi and Li Xinhen were abducted in Quetta, they were first reported to have been working at a language school run by a South Korean.

It was only after they were killed that Pakistani authorities accused the pair of being preachers who had misused business visas.

Two Koreans were detained by Pakistan's Federal Investigation Agency, and another 11 Chinese believed to be part of the missionary group were deported.

Locals in Jinnah Town, a wealthy area of Quetta where the language centre was based, said the group, while distinctly visible, kept a low profile.

They travelled around in rickshaws without security and stayed in a simple hostel in the centre of the city.

China is connecting the port of Gwadar, in Pakistan's south, with Kashgar, in China's west

"Sometimes I saw them singing and playing guitars," a local garbage collector said.

In Kharotabad, a very conservative area in Quetta's west home to Pashtun tribes and Afghan refugees, some of the Chinese women went door-to-door speaking with women about Christianity.

One boy said he overheard them saying "we are all sinners", and that they distributed leaflets, rings and bracelets. Another said he saw three women who spoke some Urdu and Pashto, and were "doing something about Christianity".

He said his mother asked them if they were Chinese, and "they said yes".

Is China-Pakistan 'silk road' a game-changer?

But once local police got wind of this, the group were taken out of the area and told foreigners should not be there.

Their efforts at proselytising didn't make much headway. Many locals given booklets and leaflets said they tore them up and threw them away.

Back to Jerusalem

In the 1940s, a movement began among Christians in eastern China to bring the gospel westwards - in the direction of Jerusalem.

Evangelists travelled to China's western provinces but when Mao Zedong proclaimed the communist People's Republic of China in 1949, ushering in a repressive era for Christians, they settled there and the "Back to Jerusalem" movement lay dormant for decades.

In the early 2000s, coinciding with China's emergence onto the global stage as a major power, the movement revived and Chinese missionaries began travelling out to what some evangelists call the "10/40 Window" - a zone between 10 and 40 degrees north of the equator that stretches from West Africa to South East Asia and is home to the least-Christian countries.

This zone overlaps significantly with the new Silk Road that China is trying to promote and in the last few years, as Chinese workers have gone overseas to these countries in droves, hidden among them have been hundreds, perhaps even thousands of missionaries, according to members of the movement.

In countries like Iran, Iraq or Pakistan, Chinese missionaries have little trouble getting in, says Pastor Danny Lee, the director of Back to Jerusalem in the UK.

"They let them straight through. They last thing they would think [a Chinese person could be] is a missionary," he said.

The movement's ambitious goal, Pastor Lee says, is to eventually have 100,000 Chinese missionaries serving across 22 countries in the 10/40 zone.

"Many of them have already left and are serving in places like Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, Iran, Iraq, North Korea, Burma and many other places as well," he said.

And violence like that seen in Quetta does not appear to put them off.

A young Chinese Christian couple sent to northern Iraq as missionaries told the South China Morning Post after the Pakistan killings that the incident was a reminder that they needed to be careful and sensitive in their work.

But they said, external they still intended to stay there indefinitely, despite the risks. "I actually feel safer here," 25-year-old Michael said, referring to the repression faced by underground churches in China.

Pastor Lee says Back to Jerusalem missionaries know the risks when they go abroad, and accept them. "They feel this is their calling and purpose and the plan that God has for them."

All-weather friends

Since the killings came to light, Pakistani authorities have vowed to better regulate the inflow of Chinese nationals to Pakistan.

Militants have targeted Chinese nationals before but the attention the case received appears to have triggered significant concern among top-level officials about implications for relations with China.

In Quetta, Chinese individuals could occasionally be seen on the streets before the May kidnapping but since then they have vanished.

In the port of Gwadar, the centrepiece of the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor, frequent attacks by separatist insurgents have denied Chinese workers the freedom of unguarded movement on the streets, reporters there say. They remain in secure compounds and move under heavy security escort.

Professor Hasan Askari Rizvi, a Pakistani political and security analyst, said that Chinese and Pakistani officials would have robustly discussed the Quetta case behind closed doors.

"The likeliest outcome would be a combined set of procedures on both sides to ensure this doesn't happen again," he said.

Indeed, China has continued to stress that it and Pakistan are "all-weather strategic partners".

But Beijing knows that as more and more Chinese missionaries follow the new Silk Road, other cases like this are bound to occur.

On 9 June, the day after IS announced the killing, Chinese foreign ministry spokeswoman Hua Chunying responded to a journalist.

"You asked about the risk in the building of the Belt and Road," she said. "I shall say that going global comes with risks."

Reporting by the BBC's Kevin Ponniah in London and M Ilyas Khan in Islamabad, BBC Chinese's Yashan Zhao in Hong Kong and BBC Urdu's Muhammad Kazim in Quetta

- Published26 March 2016

- Published22 April 2015

- Published9 June 2017

- Published5 February 2016

- Published13 August 2015

- Published4 May 2014

- Published12 September 2011