North Korea's nuclear tests: How should Trump respond?

- Published

The US is drawing up a new proposal to punish any countries doing business with North Korea

North Korea's dramatic testing of a sixth nuclear device has once again raised fears of rising tensions in north-east Asia and the prospect of war breaking out on the Korean peninsula.

The size of the latest test - equivalent to a 6.3 magnitude earthquake - suggests a step-change in the destructive power of the North's nuclear assets.

It was five to six times larger than its last test in September 2016, and potentially seven times as large as the atomic bomb that was dropped on Hiroshima.

But it is too early to assess Pyongyang's boast to have successfully tested a hydrogen bomb. The North has made similar uncorroborated claims in the past, but irrespective of the precise nature of the explosion, there seems little doubt that the destructive capacity of Pyongyang's nuclear arsenal has increased substantially.

Why does North Korea want nuclear weapons?

The North's motives for testing remain unchanged. Pyongyang's desire to acquire nuclear weapons dates from at least the 1960s, and is rooted in a desire for political autonomy, national prestige and military strength.

Added to this is Kim Jong-un's desire to secure an unambiguous deterrent to safeguard against a potential US pre-emptive attack - a key element in explaining not only Kim's sharply accelerated missile testing programme, but also the latest photo boast apparently showing him inspecting a new entirely "homemade" nuclear warhead.

While analysts are divided on whether the North's progress in developing an intercontinental ballistic missile (following its two tests in July) has enabled it to strike the United States with nuclear weapons, in some ways the technical debate is moot.

State media showed North Korean leader Kim Jong-un inspecting what it said was a hydrogen bomb

The demonstration effect of repeated missile and nuclear weapons testing makes it extremely unlikely that an American president would contemplate a direct strike on the country, other than in retaliation against a North Korean attack - a move that North Korean officials know would be suicidal.

Kim Jong-un's behaviour since taking over as the North's leader in December 2011 suggests that he is a rational actor, albeit a particularly egotistical and brutal one given his willingness to execute and purge both close family members and senior elite North Korean officials.

His actions are those of a calculating risk-taker (more so than his father Kim Jong-il) intent on thumbing his nose at President Trump, while also bolstering his legitimacy in the eyes of his own people by realising his goal of military modernisation. This objective appears to be widely popular with many North Koreans, especially those living in Pyongyang.

How should the US respond?

While the North remains the primary source of regional insecurity, an additional, and perhaps more worrying element of instability is the temperament and thinking of Donald Trump.

The US president continues very conspicuously to hint at the possibility of pre-emptive US military action against the North - a course of action that would have catastrophic consequences for the citizens of Japan, South Korea and especially the 10 million or so residents of Seoul directly in range of the North's conventional and nuclear forces.

Ultimately, a US military response to the North Korean challenge would, therefore, represent a "doomsday" scenario for America's two key regional allies as well as jeopardising the lives of the 28,500 US servicemen and personnel based in South Korea.

It is, therefore, easy to understand why both US Defence Secretary James Mattis and National Security Adviser H. R. McMaster are reportedly firmly opposed to the military option except as a last defensive resort.

South Korea and US soldiers watch a joint live firing drill in Pocheon, 65km northeast of Seoul

President Trump's bellicose sabre-rattling may be a negotiating ploy, intended to alarm Pyongyang sufficiently to deter it from further provocations, or to encourage an increasingly irritated Chinese leadership to impose decisive and punitive economic pressure on the North, most immediately through a suspension of critical crude oil supplies.

Yet if this is the intention, it does not appear to be working. The North has since April been stockpiling supplies of oil to guard against any new sanctions and the Chinese leadership, while reportedly increasingly irritated by the North, may therefore have concluded that restricting oil as either a symbolic or actual economic weapon may have limited immediate impact.

Assuming the president is neither irrational nor wilfully impulsive, nor willing to sacrifice Seoul for the interests of Washington, then the most likely response to the current crisis will be for the administration to push for much tougher sanctions against the North.

Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin is currently drawing up a new proposal to punish any third countries doing business with the North by cutting off their access to the US market. While this would certainly be a dramatic and arguably proportionate response to the new North Korean provocation, it runs the risk of being both ineffective and counter-productive.

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

Unilateral US sanctions would be hard to enforce, would potentially provoke crippling retaliatory trade sanctions by countries such as China that have balked at further across the board economic pressure on the North, and would at best, even if enforceable, take time to have a meaningful effect on the North Korean leadership.

Given the grave risks and limited benefits associated with either sanctions or military action, diplomacy and dialogue remain the best means of defusing the current crisis.

While the UN and individual nations should continue to forcefully condemn the North's behaviour, it remains the responsibility of the United States - still the world's indispensable superpower - to actively and imaginatively explore the options for some form of dialogue with North Korea.

Not talking leaves open the possibility that strategic tensions will continue. A frustrated President Trump confronted, weeks or months from now, by the failure of sanctions or political brinkmanship to bring the North to heel, may end up acting on his apparent belief that force is the "one thing" that Kim Jong-un understands.

In such a situation it is conceivable that both sides may misperceive the intentions of the other and end up stumbling into conflict that could escalate to the nuclear level - not through rational design but by accidental miscalculation.

Patient negotiation remains, therefore, a way of pointing out to the North not only the costs (both diplomatic and economic) of further provocations, but also the potential gains to be realised through moderation.

Talking is not, as President Trump has erroneously suggested, "appeasement" and represents the best way of averting military conflict and preventing the hands of the doomsday clock, for now at least, moving perilously closer to midnight.

Dr John Nilsson-Wright is a Senior Research Fellow for Northeast Asia, Asia Programme, Chatham House and Senior Lecturer in Japanese Politics and the International Relations of East Asia, University of Cambridge

- Published4 September 2017

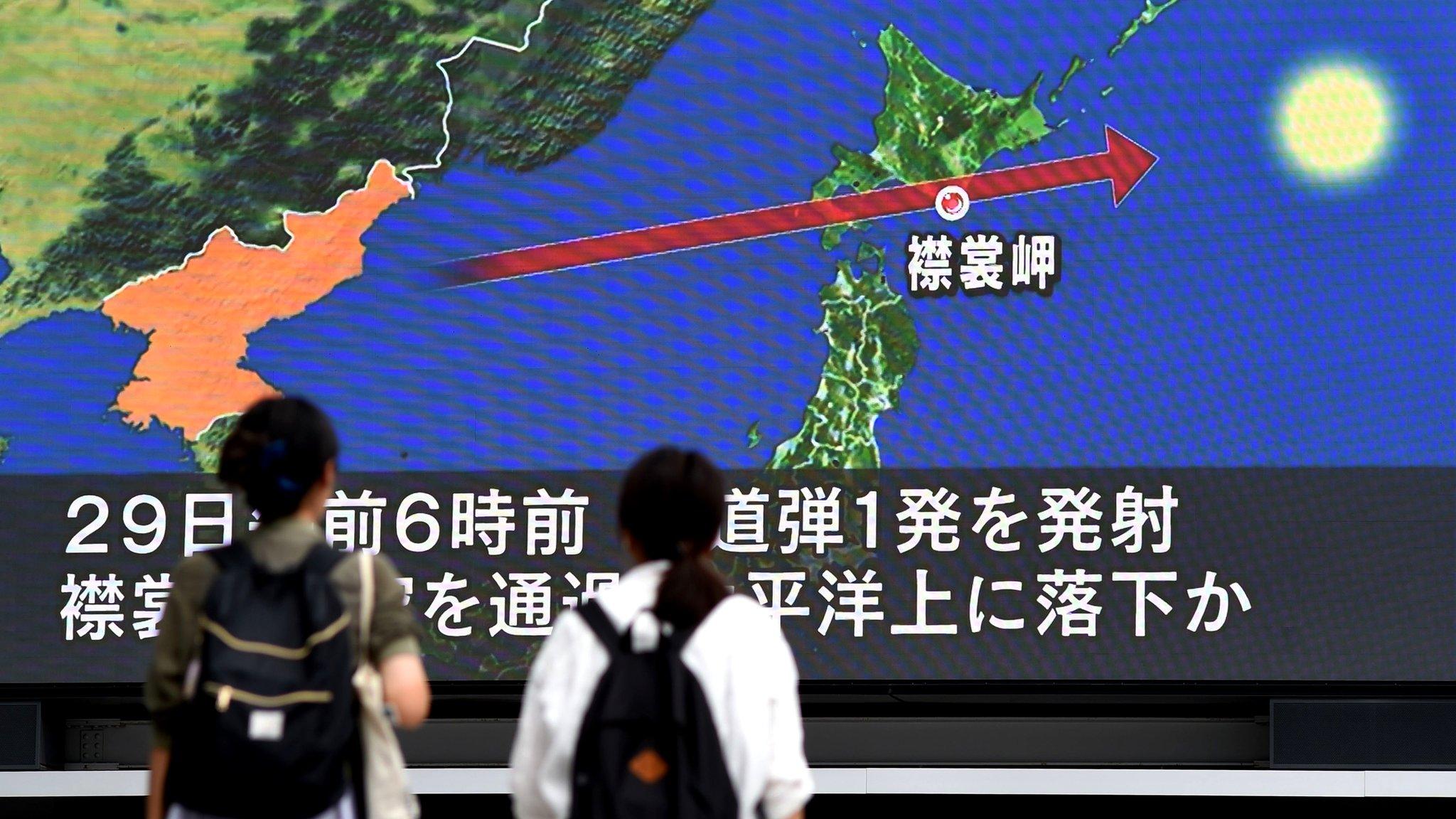

- Published29 August 2017

- Published29 August 2017

- Published5 July 2017

- Published1 May 2013