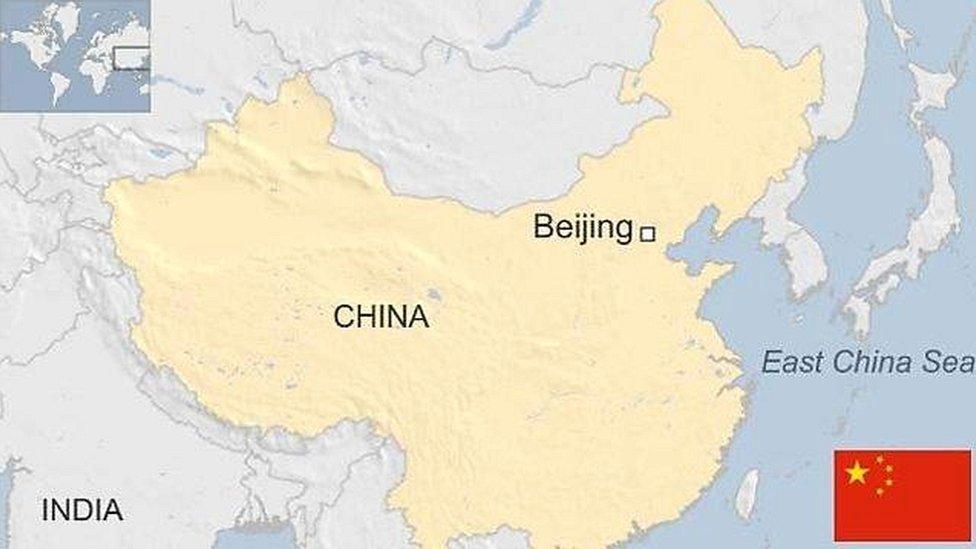

How much leverage does China have over North Korea?

- Published

The People's Republic of China, a country averse to binding, treaty-based commitments, has always enjoyed a particular relationship with its small, north-eastern neighbour.

North Korea is the only country with which China has a legally binding mutual aid and co-operation treaty, signed in July 1961. There are only seven articles in the document.

The second is the most important: "The contracting parties undertake jointly to adopt all measures to prevent aggression against either of the contracting parties by any state.

"In the event of one of the contracting parties being subjected to the armed attack by any state or several states jointly and thus being involved in a state of war, the other contracting party shall immediately render military and other assistance by all means at its disposal."

In essence, therefore, if there is a simple answer to the question of what China would need to do if North Korea is unilaterally attacked by another power - say the US or South Korea - this sentence supplies the answer.

It would, according to this treaty, be obliged to become involved - and on the North Koreans' side. This, more than anything else, shows the ways in which history continues to frame the relationship between the two.

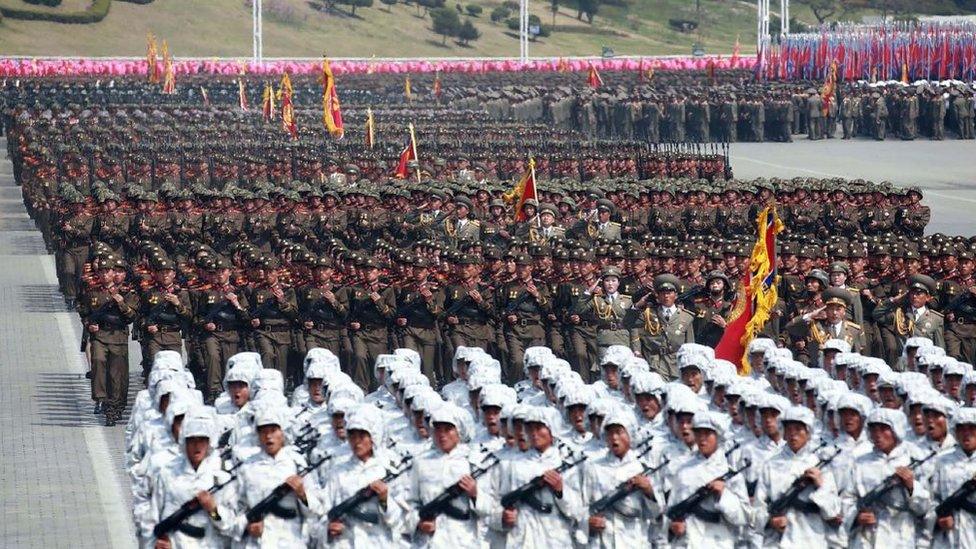

We have a very powerful precedent here. Even before the treaty in 1950, China committed a million troops to the Korean War once United Nations forces were involved. In defence of the North as a client state and buffer zone, it is more than likely to commit its much more formidable military assets.

This agreement still stands, despite the immense changes to China since the period in which it was signed.

A million Chinese troops were involved on North Korea's side in the Korean War

After the death of Mao in 1976, the country shifted from its adherence to a utopian version of socialism, and undertook widespread reforms. These resulted in the hybrid, complex system the country has today. Its economy and geopolitical prominence have burgeoned.

For North Korea, things have been different. Tepid attempts at controlled reform over the past three decades have had little success.

In the early 2000s, the Chinese hosted its former leader, the late Kim Jong-Il, and showed him special economic zones in Shanghai and examples of how to create a manufacturing, export-orientated economy servicing the capitalist West but maintaining its Marxist-Leninist system.

The attempt at persuasion evidently fell on deaf ears. North Korea's unique Juche ideology - a pure form of nationalism - meant that it resisted any attempts to copy models from elsewhere.

To this day, the market, if it exists in North Korea in any shape or form, is highly circumscribed and geared towards supporting the country's military aims and regime survival.

China's great points of leverage these days are trade, aid and energy. As the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991, North Korea's most important patron vanished almost overnight. Since that point, the reliance on China has increased to the extent that is now almost a monopoly.

Some 80% of the country's oil comes from its neighbour. Coal exports into China were immensely important - until sanctions stopped them in July last year after provocative behaviour. China has stuck to this agreement, with precipitous collapses in the North Korean economy in the ensuing year.

Late North Korean leader Kim Jong-Il with former Chinese President Hu Jintao (R) in Beijing in January 2006

Almost all of North Korea's exports are either to China, or through China to elsewhere. Some 90% of its aid comes from China. China is the only country it has air links with, and a rail line into.

It was, until the mid-2000s, the only country, too, whose banks had relations with North Korean counterparts, through accounts in Macau in particular. Monies here were frozen in a previous spate of sanctions.

Even so, one of the new targets of UN-backed measures is Chinese banks, which continue, mostly indirectly, to deal with embargoed North Korean companies or intermediaries.

The main point of Chinese leverage over North Korea is widely believed to be its oil. Stopping this would lead to an immediate, dramatic economic impact.

A few years ago, for a matter of days, the oil pipes into North Korea were closed, around the time of a previous nuclear test. China has, therefore, been willing to flex its muscles here.

North Korea's military consumes 25% of the country's GDP

But wholesale stopping of the supply, rather than temporary glitches, is a different matter. Many believe this would trigger regime crisis, or even collapse. After all, the North Koreans are already living in a subsistence economy. Taking away this final lifeline could be fatal.

There are powerful counter-arguments, however, that say things would not be so straightforward. North Korea devotes 25% of its GDP (gross domestic product) to military activity. The oil stocks there would last a few months. And that would give it time to embark on the devastating assault southwards that everyone fears, into the highly populated regions of South Korea.

It would be a suicidal mission, but as the world knows from plenty of other examples, handling those with suicide on their minds is the greatest challenge.

Nor would North Korea be compliant in other areas as it collapsed. Refugees would swarm across the border into China. A vacuum would appear. China would be faced with its worst nightmare - a space which the US and its allies might try to occupy.

For all its seeming points of leverage and influence, therefore, the most remarkable thing about China and North Korea is the ways in which, at a time when the rest of the world is agonising over how to deal with a renascent, confident, powerful-looking China, this narrative is so brutally undermined by the ways in which its small, impoverished neighbour almost daily exposes its impotence.

About this piece

This analysis piece was commissioned by the BBC from an expert working for an outside organisation.

Kerry Brown is professor of Chinese studies and director of the Lau China Institute at King's College, London.

- Published19 July 2023

- Published25 August 2023