Myanmar Muslims fear further 'turning of the tide'

- Published

Various reports point out that Muslims have been living in Myanmar for centuries

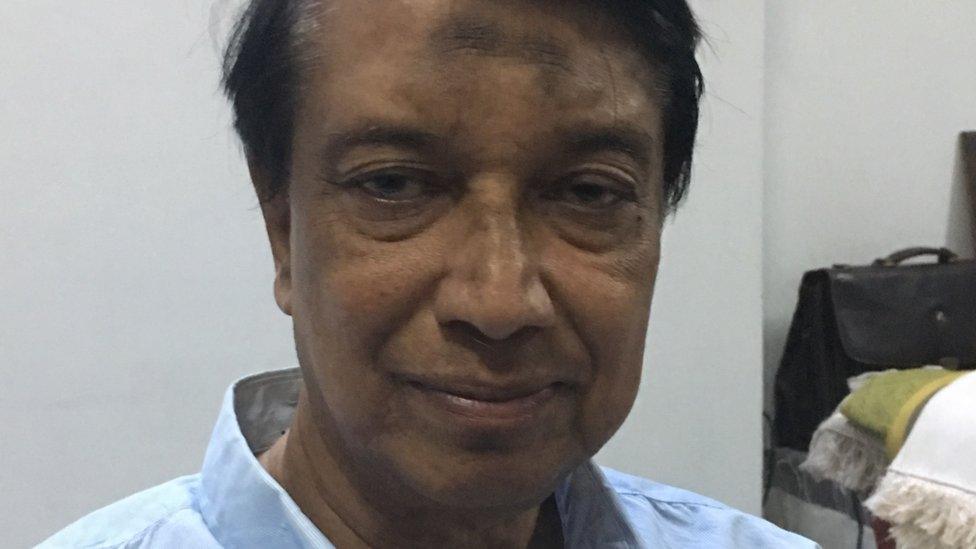

For Tun Kyi, Myanmar is home. He was born and brought up in the country and, like thousands of other Burmese, he was also protesting in the streets for democracy during the military junta's rule. He spent 10 years in prison.

Today, he is playing an active role in the Former Political Prisoners Society of Myanmar. He was one of those Muslims who hoped the community would get its rightful place in society after the end of military rule in 2010.

"The situation changed after the violence in Rakhine state in 2012," he said. "The tide is not just against Rohingya Muslims but also against the Muslim community as a whole."

Mr Kyi's ancestors migrated from India to Buddhist-majority Myanmar, also known as Burma, generations ago.

More than half-a-million Rohingya Muslims recently fled from Myanmar into Bangladesh

Former political prisoner Tun Kyi argues that things changed in Myanmar after the 2012 violence in Rakhine state

The clashes between Buddhists and Muslim Rohingyas in western Rakhine state in 2012 drove 140,000 people out of their homes. Most of those displaced, particularly Rohingya Muslims, ended up seeking refuge in neighbouring Bangladesh.

I was invited to a mosque in Yangon during Friday prayers. Hundreds of men, many wearing their Islamic caps, were streaming in and getting ready for prayers.

The discussions I had with some of the worshippers reflected a sense of uneasiness among the community following the latest round of violence in Rakhine.

The violence was triggered after Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army (Arsa) - a Rohingya Muslim militant group - launched simultaneous attacks on Myanmar security check posts in the region on 25 August. The Myanmar military swiftly launched what it described as counter-terrorism operations.

More than half-a-million Rohingya Muslims have since fled the violence, bringing with them reports of rape and extra-judicial killings.

Many Rohingya Muslims who have fled into Bangladesh are living in camps

Senior UN officials and human rights groups have described the exodus of Rohingya Muslims as "ethnic cleansing"- a charge vehemently denied by the government of Myanmar.

"The problem there in Rakhine state is terrible," says worshipper Muhammad Yunus. "There are concerns that the violence may spill over to Yangon and other places."

He says that Muslims in other parts of the country are very careful about what they say and do in their day-to-day affairs.

"There are people who were born and raised in Rakhine state now living in Yangon," says Mr Yunus. "They are worried about their family members and relatives back home."

Muslims have been weeded out from important government positions, says Al-Haj U Aye Lwin

Muslims are believed to constitute about 4.5% of Myanmar's population of 53 million. The estimate also includes Rohingya Muslims, but Muslim community leaders argue that their real population could be twice the official figure.

Various reports point out that Muslims have been living in Myanmar for centuries. Their numbers increased during British colonial rule when many of them either migrated or were brought in from the Indian subcontinent.

Rohingya Muslims - who are linguistically different from Muslims in south and central Myanmar - lived mostly in western Rakhine state.

Islamic community leaders say they are disappointed that despite the numbers there is no single sitting Muslim member of parliament.

Watch: Who are the Rohingya?

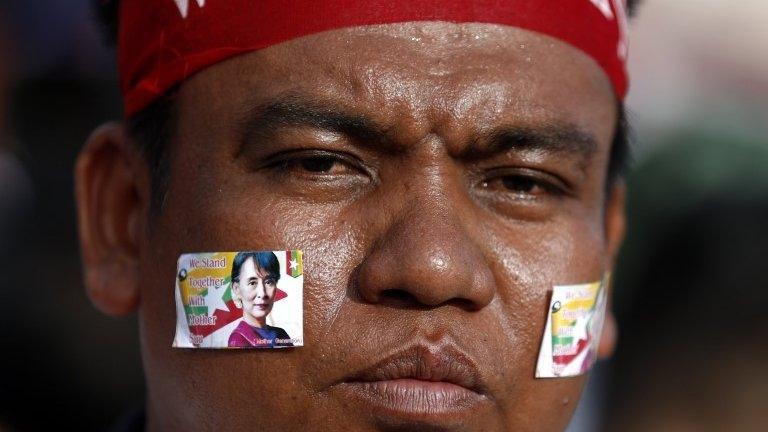

The elections in 2015 brought Aung San Suu Kyi's National League for Democracy (NLD) to power, but even the NLD did not field any Muslim candidates.

"We feel that we are being discriminated against in every way, you name it," says Al-Haj U Aye Lwin, the chief convener of the Islamic Centre of Myanmar.

He says that has been the case since 1962 - when the military seized power - and Muslims have been weeded out from important government positions.

"Now you don't find even one junior [Muslim] officer in the police force, let alone the army," says Mr Lwin. He argues that the discrimination mainly emanates from the government and is not so widespread at grassroots level.

Mr Lwin is one of the members of an Independent Advisory Commission, headed by the former UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan, to find solutions to the conflict in Rakhine state.

Muslims - including these Shia in Yangon - constitute about 4.5% of the country's 53 million population

Rohingya Muslims - seen here crossing the Naf river from Myanmar into Bangladesh - are linguistically different from Muslims in south and central Myanmar

Muslims in Yangon mix with other communities even though many are feeling nervous about developments in Rakhine state

The commission was set up by Ms Suu Kyi in 2016. It submitted its recommendations on 24 August - a day before the latest round of violence started.

Mr Lwin says Ms Suu Kyi may not be perfect, but "she is our only hope". He argues that the state counsellor has done whatever she could to solve the Rohingya issue.

"If she comes out openly and started to speak for the Muslims, it will be a political suicide for her," he says. "We don't want that to happen."

He warns that the West should understand that if she is discredited and removed from power, Myanmar risks a return to authoritarian rule.

"Only the dictators will come back," he cautions.

Where have the Rohingya fled to?

- Published11 October 2017

- Published9 October 2017

- Published19 September 2017

- Published19 September 2017

- Published19 September 2017

- Published20 September 2017

- Published7 September 2017

- Published11 September 2017

- Published19 September 2017