How will the US move to cut aid affect Pakistan?

- Published

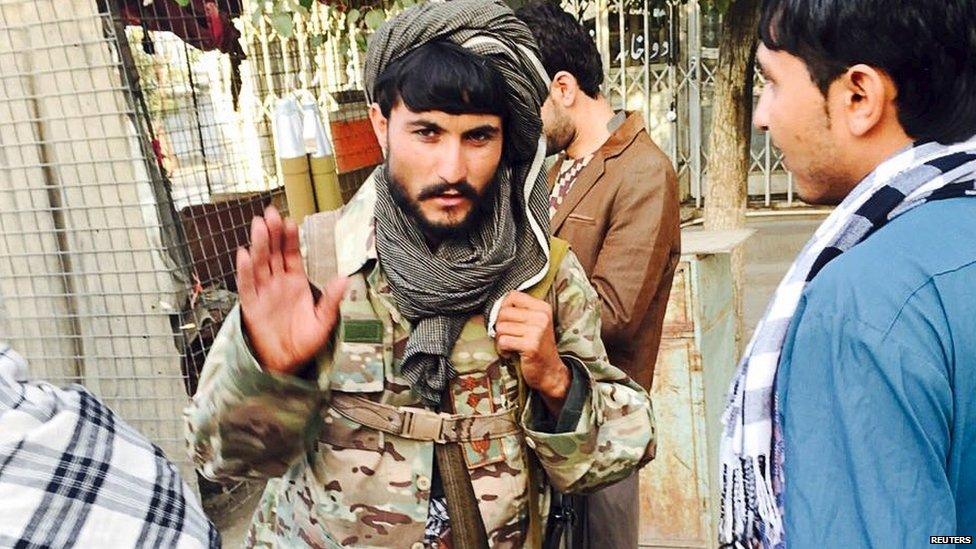

Pakistani protesters have denounced the cuts

The Trump administration says it is cutting almost all security aid to Pakistan until it deals with terrorist networks operating on its soil. But will the cuts have any impact, asks the BBC's M Ilyas Khan.

The US has yet to announce exactly how much aid will be cut - but defence experts believe the total impact of the visible aid suspension may fall in the range of more than $900m (£660m).

This includes the suspension of $255m due to Pakistan for military equipment and training under the Foreign Military Financing (FMF) fund, and $700m under the Coalition Support Fund (CSF) - paid to Pakistan for conducting operations against militant groups.

Experts believe the total financial impact of an adverse US policy on Pakistan could be much higher than this though, especially as the US state department has said an unspecified amount of other security assistance managed by the department of defence could be cut.

How reliant is Pakistan on US security aid?

Security experts believe the cuts are likely to put a squeeze on the Pakistani military, at least in the short run.

"If the US pipeline dries up, the military's immediate plans for upgrading of materiel and manpower resources will be stalled," says Prof Hasan Askari Rizvi, a defence analyst and author of the book, Military, State and Society in Pakistan.

"It will also be a setback in the long term as China or any other friendly country cannot totally replace the resources that Pakistan needs to keep its military machine well oiled," he says.

This could explain the government's response to the cuts.

While Pakistani politicians have been quick to condemn the US in the media, with Foreign Minister Khwaja Asif calling the US a "friend-killer" whose attitude "matches neither that of a friend nor an ally" and Defence Minister Khurram Dastgir warning against "American mischief", other government reaction has been more cautious.

The foreign office talked of Pakistan's efforts to bring peace to the region, which it said was done mostly at its own cost - $120bn over 15 years - and argued that "arbitrary deadlines, unilateral pronouncements and shifting goalposts are counterproductive in addressing common threats".

Meanwhile, in a written reply to the BBC an army spokesman said Pakistan had "never fought for money but for peace".

Why Trump is taking aim at Pakistan

Experts believe that, despite the verbal sparring on TV, the military will actually be tempted to put a squeeze on militant groups that are believed to have sanctuaries, recruitment and training facilities on Pakistani soil - just as the US has demanded.

"Though it may not be visible, there certainly will be some changes in Pakistan's approach to militants," says Prof Askari.

"At the very least, they may ask groups like the Haqqani network to go low-key for a while."

Will Pakistan try to retaliate?

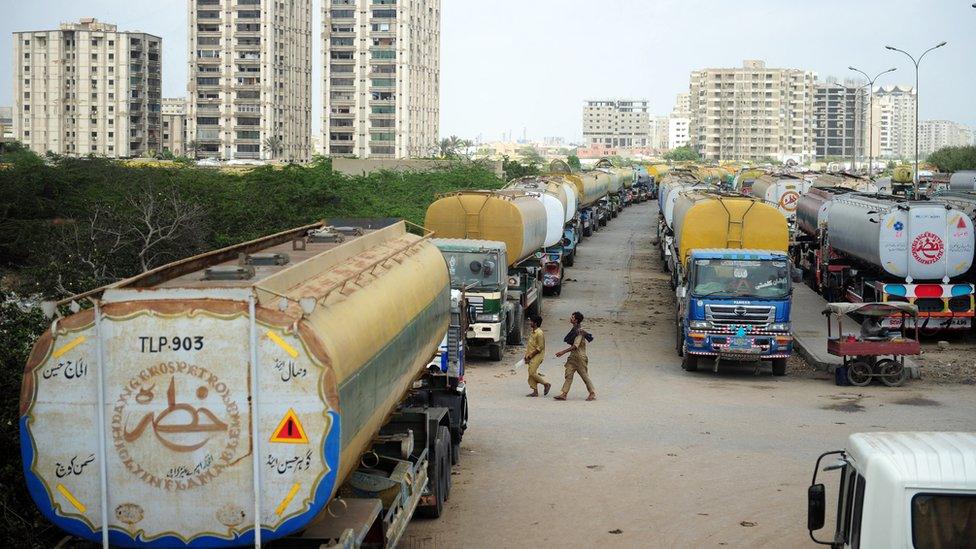

Pakistan's main leverage with the US lies in its geographical location and its role in Afghanistan - the fact that it controls the only supply line into the landlocked country for international troops, and has influence over the militant groups that are fighting there.

The question is, will Pakistan try to press its advantage by shutting overland access of US supplies to Kabul?

It's happened before. Pakistan blocked this route for several months in 2011 and 2012 after a series of embarrassing events, including the killing of Osama Bin Laden in a secret operation by US Navy Seals, and the bombing of a Pakistani post by American jets that killed more than 20 soldiers.

But Prof Askari believes Pakistan may not take that route this time. In 2011, the US appeared more accommodating, following Pakistani anger at the US operation and the bombing of the post.

Pakistan blocked overland Nato supplies into Afghanistan for months in 2011

But this time, the anger is coming from the US side - and too drastic a move from Pakistan could aggravate the situation.

"Pakistanis may create hurdles or cause delays in the transit of such supplies, but they are unlikely to block it completely, because that could lead to suspension of all ties," Prof Askari says.

At the moment, the US is still providing Pakistan with non-military aid. And even in the case of military assistance, it is believed the US may follow a "condition and issue-based approach" where funds would be released for identified and measurable actions.

By contrast, a total cut-off of relations would mean that the US could remove Pakistan from its list of major non-Nato allies, designate it as a state sponsor of terrorism, or work with India and Afghanistan to more aggressively counter its interests in the region.

Neither side is likely to want such a drastic move.

Analysts have pointed out that the US does not want instability in Pakistan.

Pakistan has one of the world's fastest-growing nuclear programmes, as well as several Islamist terrorist organisations on its soil, so "America and its allies are rightly concerned that any instability in Pakistan may result in terrorists getting their hands on Pakistan's nuclear technology", Christine Fair, a US-based South Asia expert, says, external.

- Published3 January 2018

- Published1 January 2018

- Published25 August 2017

- Published22 October 2015