How Aung San Suu Kyi sees the Rohingya crisis

- Published

What has Aung San Suu Kyi said about Rohingya Muslims?

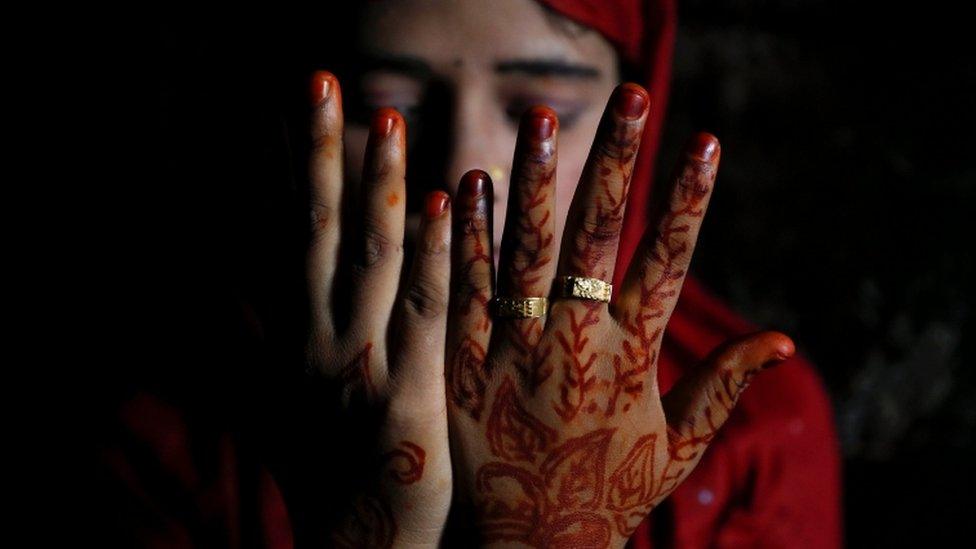

Myanmar leader Aung San Suu Kyi has overseen what is said to be the world's fastest growing refugee crisis, as hundreds of thousands of Rohingya Muslims flee to neighbouring Bangladesh.

Risking death by sea or on foot, more than half a million have fled persecution in northern Rakhine state since August 2017. The government sees the Rohingya as illegal immigrants from Bangladesh and denies them citizenship

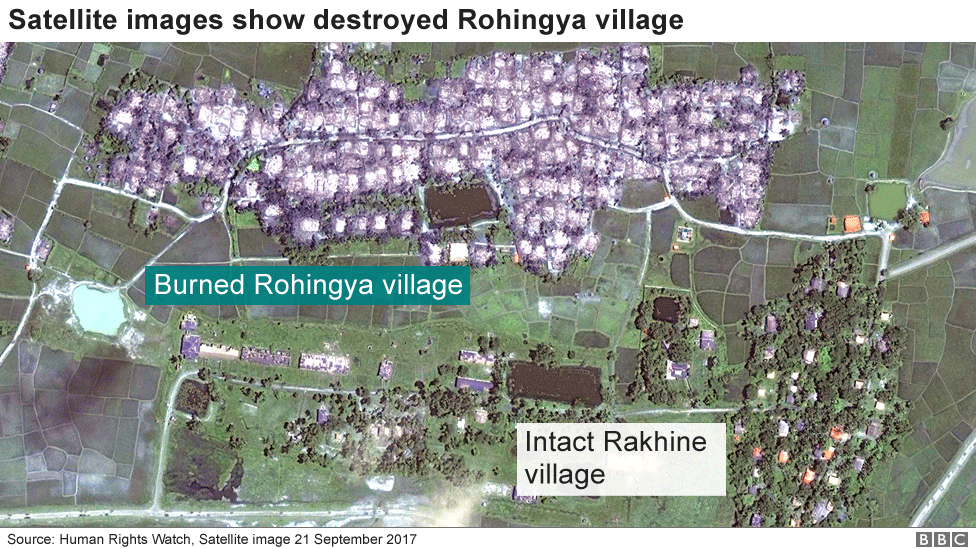

Many of those who have fled describe troops and Rakhine Buddhist mobs burning their villages and attacking civilians. But Myanmar's military says it is fighting Rohingya militants, and denies ever targeting civilians.

Ms Suu Kyi, a Nobel Peace Prize winner who lived under house arrest for many years for her pro-democracy activism, is facing allegations that she has failed to speak out over violence against the Rohingyas.

So what has she said?

Human rights heroine

In 2012, more than 20 years after being awarded the Nobel Peace Prize, Ms Suu Kyi gave her acceptance speech in Oslo. She said the prize "had drawn the attention of the world to the struggle for democracy and human rights in Burma [Myanmar]".

"Burma is a country of many ethnic nationalities and faith in its future can be founded only on a true spirit of union," she said, before reading some of her "favourite passages" from the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

"Ultimately our aim should be to create a world free from the displaced, the homeless and the hopeless, a world of which each and every corner is a true sanctuary where the inhabitants will have the freedom and the capacity to live in peace".

They are the words of someone who, for many years, was hailed as the heroine of the human rights community. From the early 1990s until her final release from house arrest in 2010 she was a brave symbol of defiance against what was then a brutal military dictatorship.

Thousands of Rohingya refugees flee to Bangladesh

Staying quiet

The same year she delivered her Nobel speech, an outbreak of communal violence in Myanmar saw more than 100,000 Rohingya people displaced and forced to live in makeshift refugee camps. At least 200 people were killed in fierce clashes between Buddhist and Muslim communities in Rakhine state.

Ms Suu Kyi, who was leader of the opposition at the time, sought to reassure the international community and pledged to "abide by our commitment to human rights and democratic value".

But critics accused her of staying quiet, and one senior British minister told The Independent newspaper: "Frankly, I would expect her to provide moral leadership on this subject but she hasn't really spoken about it at all."

The displacement of the Rohingya continued in 2013, and by the autumn more than 140,000 people had been forced to leave their homes. The violence had spread from Rakhine state to other areas including central Myanmar, and substantial international assistance was being channelled through NGOs and UN agencies.

Burma's opposition leader Aung San Suu Kyi: "We cannot become a genuine democratic society with the [current] constitution"

Blaming government

Ms Suu Kyi spoke to the BBC's Mishal Husain about the crisis in October of that year. She blamed the continued violence on a "climate of fear", and denied that Muslims had been subjected to ethnic cleansing.

"Muslims have been targeted but Buddhists have also been subjected to violence," she said. "This fear is what is leading to all this trouble".

She said that it was down to the government to bring an end to the violence.

"This is the result of our sufferings under a dictatorial regime. I think that if you live under a dictatorship for many years people do not like to trust one another - a dictatorship generates a climate of mistrust," she added.

In 2015, Ms Suu Kyi faced calls from around the world to condemn the ongoing crisis. The Dalai Lama said that he had twice urged her to act over the issue.

"I met her two times, first in London and then the Czech Republic. I mentioned about this problem and she told me she found some difficulties, that things were not simple but very complicated," he told The Australian.

In November of that year, Ms Suu Kyi's National League for Democracy party won a landslide election victory. Hundreds of thousands of people, including the Muslim Rohingya, were not allowed to vote, and no voting took place in seven areas where ethnic conflict was rife.

She spoke to the BBC's Fergal Keane about the Rohingya crisis as votes were still being counted. "Prejudice is not removed easily and hatred is not going to be removed easily… I'm confident the great majority of the people want peace… they do not want to live on a diet of hate and fear," she said.

Ms Suu Kyi could no longer defer responsibility to the government. Her stock response before the 2015 election was that it was a problem for the leadership to solve. Now she had to prove she was willing to deal with it.

But she finds herself in an awkward position.

Ms Suu Kyi makes most of the important decisions, but the military retains control of three vital ministries - home affairs, defence and border affairs. That means it also controls the police. The military is the real power in northern Rakhine State, along the border with Bangladesh.

So Ms Suu Kyi has very little control over events there. Speaking out in support of the Rohingya would almost certainly prompt an angry reaction from Buddhist nationalists and military officials. Not to mention the general public who have very little sympathy for the Rohingya.

This goes some way to explaining why she has rarely spoken out in their favour.

Watch: Drone footage from last October shows the extent of sprawling camps on the Bangladesh border

Playing it down

In 2016 the crisis escalated. Some government officials blamed a militant Rohingya group for the deaths of nine police officers who were killed in co-ordinated attacks near Maungdaw. A massive security operation was launched in response, and Rohingya activists said more than 100 people were killed in the crackdown.

In November 2016, a senior UN official told the BBC the new military offensive was a "textbook example of ethnic cleansing" - something Myanmar denies.

Some observers said Ms Suu Kyi's failure to condemn the ongoing violence was an outrage. She avoided journalists and press conferences, but when forced, said the military in Rakhine was operating according to the "rule of law". Few believed that to be the case.

When she did occasionally comment on the situation, it was to play it down or suggest that people were exaggerating the severity of the violence.

"I'm not saying there are no difficulties,'' she told Singapore's Channel NewsAsia in December 2016. "But it helps if people recognise the difficulty and are more focused on resolving these difficulties rather than exaggerating them so that everything seems worse than it really is.''

Tun Khin, from the Burmese Rohingya Organisation UK, said her failure to defend the Rohingya was "extremely disappointing". "The point is that Aung San Suu Kyi is covering up this crime perpetrated by the military," he said.

Aung San Suu Kyi was questioned by the BBC's Fergal Keane in April on why she hadn't done more for the Rohingyas

In an exclusive interview with the BBC last April, she acknowledged problems in Rakhine state but she said ethnic cleansing was "too strong" a term to use.

"I don't think there is ethnic cleansing going on. I think ethnic cleansing is too strong an expression to use for what is happening," she said.

"I think there is a lot of hostility there - it is Muslims killing Muslims as well, if they think they are co-operating with the authorities," she added.

Ms Suu Kyi has missed several opportunities to speak publicly about the issue. She did not attend the UN General Assembly in New York last September, and later claimed the crisis was being distorted by a "huge iceberg of misinformation".

"We make sure that all the people in our country are entitled to protection of their rights as well as, the right to, and not just political but social and humanitarian defence," she said. Her comments are at odds with observers on the ground, who say the whole refugee population - almost one million people - require food aid.

That same month, she also said she felt "deeply" for the suffering of "all people" in the conflict, and that Myanmar was "committed to a sustainable solution… for all communities in this state".

Mounting pressure

The international pressure against Ms Suu Kyi has continued to mount since then.

In November last year, she was formally stripped of an honour granting her the Freedom of Oxford because of her muted response to the Rohingya crisis. Musician Bob Geldof handed back his Freedom of Dublin award to protest against the inclusion of Ms Suu Kyi on the honours list.

In December, the UN human rights chief, Zeid Ra'ad Al Hussein, did not rule out genocide charges against Ms Suu Kyi and criticised her for failing to use the term "Rohingya". "To strip their name from them is dehumanising to the point where you begin to believe that anything is possible," he said.

The BBC asked Ms Suu Kyi and the head of the Myanmar armed forces for a response. But neither of them replied.

Her failure to denounce the military or address allegations of ethnic cleansing has been criticised by world leaders and groups such as Amnesty International.

The pressure has continued to grow this year, with veteran US diplomat Bill Richardson resigning from an international panel set up by Ms Suu Kyi to advise on the Rohingya crisis.

He claimed the panel was a "whitewash" and accused Ms Suu Kyi, his long-time friend, of lacking "moral leadership". Myanmar accused him of pursuing "his own agenda".

- Published16 January 2018

- Published15 January 2018

- Published8 January 2018

- Published23 January 2020