Asma Jahangir: Who will succeed the woman who fought for Pakistan’s soul?

- Published

She triumphed over adversity long before she became a lawyer

Last month one of modern Pakistan's most extraordinary women died. Tributes described Asma Jahangir as a champion of human rights and a defender of the oppressed.

But it's hard to see who will now take on her fights, as the BBC's M Ilyas Khan reports.

It has been said that no combination of the tributes paid to Asma Jahangir can adequately define her, but perhaps the one that best encapsulates what it was like to come up against her was "street fighter".

Pakistan in 2018 is a place which still faces many of the problems she spent decades fighting. It is a deeply divided society, where invisible forces battle over the direction of the country, where people suddenly disappear, and where, rights groups say, abuses are still routine.

She took on oppressive military regimes and fought relentlessly against abuses, she set up legal aid firms and the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan (HRCP).

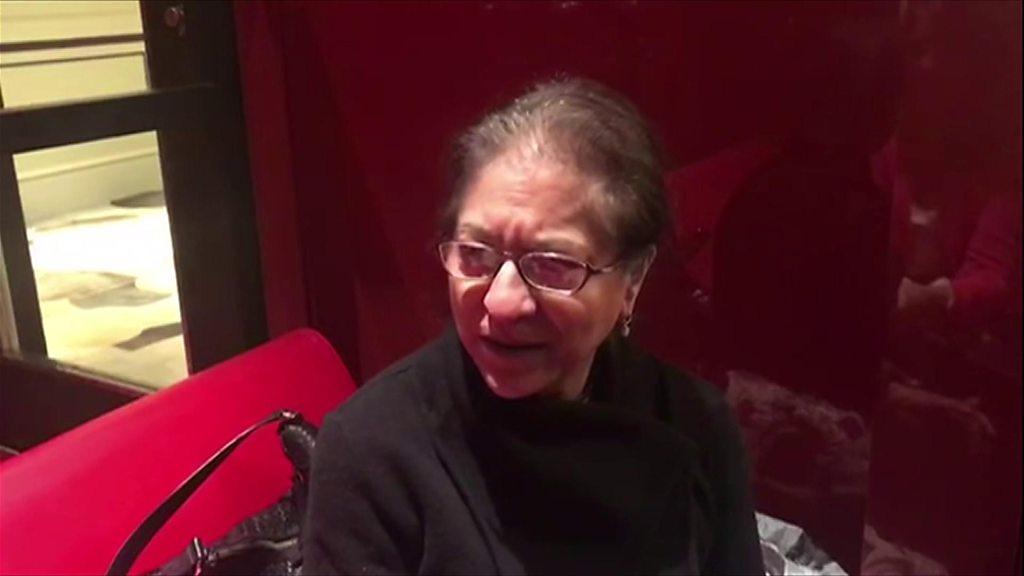

Asma Jahangir spoke to the BBC in London just a week before her death

She worked for the rich and the poor. But she was hated by those powerful interest groups who promulgate a conservative vision of religion and patriotism, thought to be backed by elements in the military.

They would not tolerate her vision of Pakistan.

But Ms Jahangir understood this polarised Pakistan and through it blazed a path that she believed could help the nation make the right choices.

'We can't live in her shadow forever'

In the wake of her death, many have said that there are no fighters quite like her left.

There is the HRCP she set up, legal firms manned by some strong characters, but without her towering personality that commanded global authority, activists have felt a vacuum.

At her funeral, mourners wailed that with Ms Jahangir gone they were now orphans. But Ismat Shahjahan, a left-wing activist who's been on the scene since the 1980s, had this to say:

"It may be true, but it reflects our own weakness. Whenever a challenge to our way of thinking arose, Asma was there to respond to it, and we didn't have to try much harder.

"But now she's gone, and we have to realise that we can't live in her shadow forever; we have to pull our act together and start tackling those challenges ourselves. Mourning her death won't work, but emulating her life will."

The death of Asma Jahangir was mourned by many of her colleagues

Thousands turned up to bid her farewell

The essence of her success, friends have said, was her unique courage.

She never minced her words. In one television interview, she called army generals "duffers", saying they only "play golf, have parties, grab plots of land," and are in the "habit of using our children as their human shields".

"Sit in the barracks. You have your plots. Eat, drink, have a party, but leave us alone," she advised.

She was equally harsh on religious lobbies.

She said she was "against all religious extremism. I'm in fact a secular person. I consider all religions equal, and I don't have a religion of my own".

Asma Jhanghir's childhood and family were steeped in politics

This was a daring - some would say rash - admission to make in a country with harsh Islamic laws implemented not only by courts by also vigilante groups carrying out street justice.

And there were consequences.

In 2005, during a riot in Lahore, the police tried to disrobe her in public, reportedly on orders from the government which was headed by military ruler Pervez Musharraf. They were restrained by her supporters, but they did succeed in tearing off her shirt, baring her back.

What was she doing at that point? She had been trying to hold a mixed gender marathon to highlight violence against women.

A combative spirit

In 2013, a leaked American intelligence report revealed that elements within Pakistan's security establishment had plotted to assassinate her, after she embarked on a legal campaign to recover missing political activists in the restive province of Balochistan, where the military had gone in to suppress an armed insurgency.

Despite attempts on her life, she never left the country or even went into "hibernation", as advised by friends. Instead, she retaliated with a combative spirit.

In 2009, she led a protest rally in Lahore against the public flogging of a veiled woman

Perhaps she was protected by her global reputation. That same leaked US report warned of an "international and domestic backlash" should anything happen to her.

This is a luxury afforded to few in Pakistan where there are many faceless campaigners who work just as hard but suffer for it too.

But even her childhood and family was steeped in Pakistan's political division, quite literally.

Pakistan's first general election held in 1970 was won by the Awami League, a party based in what was then called East Pakistan.

West Pakistan, which dominated the country and controlled East Pakistan's resources, failed to transfer power in time, sparking a rebellion in East Pakistan which ended in it seceding from West Pakistan and emerging as an independent country, Bangladesh, after military intervention by Pakistan's arch rival India.

Asma Jahangir's father Ghulam Jillani was involved with the Awami League and was jailed when he criticised military action against Awami League supporters in East Pakistan.

The anger and frustration felt in Pakistan made people like Mr Jillani targets, painted as traitors, Hindus and agents of India.

This 1995 picture shows Asma Jahangir as the Chairperson of the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan

One of Asma Jahangir's acquaintances shared a story.

One evening in 1973 she was at a neighbourhood party where some girls began telling others to beware as there was a traitor in the house.

When she heard this, the young Jahangir commandeered the microphone and let them all have a piece of her mind. Then in frustration she stepped out onto the lawn alone and broke into tears.

That's when Tahir Jahangir, the son of a businessman and a neighbour, came up from behind and comforted her. They were married in 1974.

Setting a precedent

Another example of triumphing over adversity proved to be historic and came on the legal front, long before she became a lawyer.

When her father was arrested on charge of treason he sent the family a message asking them to file a petition for his release. Asma went to a lawyer who, believing she was a minor, asked her where her mother was.

"My mother had at that time gotten very depressed and upset, and had taken sleeping pills and gone to sleep.

"So I told him that you write down the petition and I'll drive home and get it signed by her. Then he looked at me and asked, 'how old are you?' I said 18. He said you need not (take it to your mother). You can just sign it yourself," she recounted in an interview once.

Ms Jahangir leaves behind a powerful legacy

This case, titled Asma Jillani versus the Federation of Pakistan, is one of the most widely quoted precedents in case law, and is the only case in Pakistan's history in which a military dictator was declared a usurper.

Ismat Shahjahan is now putting together a women's democratic front, a reincarnation of the socialist campaigners that burst onto the scene in 1968 as a military dictatorship was about to be ousted and before the secession of East Pakistan.

Perhaps her successor will be found among them.

- Published11 February 2018

- Published11 February 2018

- Published5 September 2013

- Published15 March 2024