Korean talks: What will come from Kim-Moon meeting?

- Published

A thaw in South and North Korean relations first began in the lead-up to the Winter Olympics

South Korean President Moon Jae-in and North Korean leader Kim Jong-un will meet on Friday in an act of diplomacy not seen for more than a decade.

This rare dialogue comes after months of improving relations between the two countries and will pave the way to proposed talks between the United States and North Korea.

Denuclearisation and peace on the peninsula will top the agenda. While analysts are sceptical Pyongyang will agree to give up its nuclear weapons, the summit carries promise for both Koreas. Each side has other problems - like sanctions and separated families - they're likely to bring to the negotiating table.

How significant is this meeting?

It's a big deal. As well as being the first time Korean leaders have met since 2007, it marks the first summit of its kind for Mr Kim. Unlike his meeting with Chinese counterpart Xi Jinping - cloaked in secrecy and confirmed after the event - part of the Korean talks will be televised live.

"It's his coming-out party," said James Kim, director of the Asan Institute of Policy Studies. "Kim Jong-un has never had this kind of meeting before."

He is following in the footsteps of his father. Kim Jong-il met the presidents of South Korea at two summits: first Kim Dae-jung in 2000 and then Roh Moo-hyun in 2007.

The meetings were designed to address the nuclear threat and foster economic co-operation between the Koreas, and for his work on engagement Kim Dae-Jung was awarded a Nobel Peace Prize, external.

Some gains were made - the Kaesong industrial complex was established and families torn apart by war reunited.

But disarmament remained elusive and repeated nuclear provocations - coupled with conservative governments in Seoul taking a harder line on Pyongyang - derailed peace efforts. Attempts to draw North Korea out of isolation and build more reliance on the South have since been criticised.

Asan Institute's Dr Kim says some in South Korea would argue much of the aid and financial assistance sent to North Korea - designed to convince it to rein in its nuclear ambitions - was not used as had been intended.

"Some people argue it made it worse if anything. They believe it fed into North Korea becoming a nuclear power."

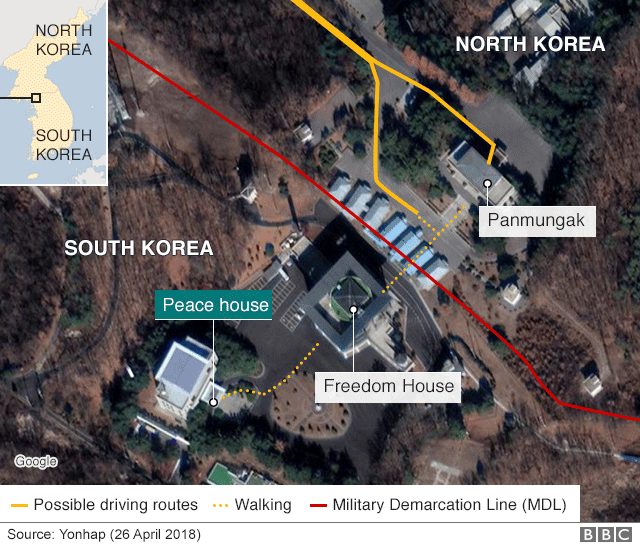

Kim's route to the summit venue

What does South Korea want?

A decade or so later, against a backdrop of mounting hostilities and threats, Seoul has steered Pyongyang back to the table.

President Moon, whose involvement in inter-Korea talks stretches back to his time as a top aide to former President Roh, took office last year pushing for more engagement with the North.

"There's no question he wants reconciliation to be part of legacy," says Ji-Young Lee, assistant professor at the American University School of International Service.

Mr Moon's hopes for the summit in Panmunjom are clear., external The leader has said a peace treaty between the two Koreas - which are technically still at war - "must be pursued" to conclude the longstanding conflict on the peninsula.

Mr Moon played a role in previous attempts to engage with North Korea

The Ministry of Unification, which oversees the relationship with North Korea, lists denuclearisation and reduced military tensions as the chief goal, followed by forging closer economic and social ties with North Korea. That may include reopening the Kaesong complex.

The site at Kaesong, an unusual example of economic co-operation by the Koreas, was shut down in 2016 after Seoul said the North was taking workers' wages and diverting the funds to support its nuclear ambitions.

President Moon says he will reopen the complex, which at its peak employed around 55,000 North Korean workers at South Korean-owned factories, if progress is made toward denuclearisation.

Reunions for the 60,000 family members separated by the Korean War will also be up for discussion. Those meetings last took place in 2015, before relations soured once again, in part over Pyongyang's nuclear programme. The release of foreigners held in detention by North Korea is also expected to be on the table.

What about North Korea?

North Korea's goals aren't as obvious. Many analysts say punishing sanctions are the reason Mr Kim is now ready to talk.

Sanctions enforced by the US and the United Nations, designed to cripple the North Korean economy, were ramped up last year after an escalation of military threats.

Asan's Dr Kim says North Korea sees engagement with the South as "the only way to get Washington to come down and talk with them" about issues like sanctions.

Other moves signal a desire for sanctions relief. A week before the historic summit, North Korea said it was putting a stop to all nuclear tests and launches of intercontinental ballistic missiles ahead of the historic summit. These have been major provocations in the past.

The moves were welcomed by Mr Moon and crucially, in the North Korean leader's eyes, by US President Donald Trump.

Dr Euan Graham, director of international security at the Lowy Institute, says for Mr Kim, all roads lead to the US and talking to Mr Moon "is the price he has to pay" to get there. And securing a stage with Mr Trump could give the isolated leader a win at home.

American University's Prof Lee says Mr Kim wants to be "treated like an equal to US leaders".

"We tend to think dictators can do anything but he's constantly under pressure. He has to worry about his own standing in North Korea."

In March, Mr Kim told a South Korean delegation he was "committed to denuclearisation"

What is likely to be achieved?

Optimism that talks are happening - the Unification Ministry says more than three-quarters of South Koreans are "positive" about the summit - is tempered by hopes for what they can realistically achieve.

Mostly they are seen as a starting point, towards both potentially unifying the Koreas and toward ridding Pyongyang of nuclear weapons.

"These talks could be some kind of helpful launching pad," says Prof Lee, who expects plenty of agreements and follow-up exchanges to follow the summit.

Eyes will be on the connection between the two leaders. Asan's Dr Kim says success is dependent on President Moon and Mr Kim's "chemistry" and whether the pair get along.

"I think this will be a very good meeting for both leaders. But in terms of whether it will lead to denuclearisation, I'm not so sure."

- Published24 April 2018

- Published25 April 2018

- Published21 April 2018

- Published21 April 2020

- Published9 March 2018

- Published10 January 2018

- Published10 January 2018