Park Geun-hye: Poisoned chalice of South Korea's presidency

- Published

The downfall of the country's first female leader is not the first - but the latest in a number of presidential scandals

South Korea has a problem with its presidency. It seems to be almost impossible for the country's heads of state to steer clear of political scandal during or after their tenures.

Former president Park Geun-hye, the country's 18th - and first female - leader, was jailed after being found guilty of abuse of power and corruption.

She made history as the first South Korean president to be impeached but is far from alone in becoming mired in controversy.

The country has only been a stable democracy for a few decades but every leader in the democratic era has been embroiled in a political scandal involving money, directly or through loved ones.

Her predecessor, Lee Myung-bak, was investigated as a presidential candidate over allegations he was involved in stock price manipulation. Those allegations recently resurfaced against him.

Dismissing the accusations as "political retaliation", he has been refusing to co-operate with the prosecution's investigation. His brother, meanwhile, has served time in prison for accepting cash from businessmen in return for government influence.

Before him, a controversy surrounding the 16th leader, Roh Moo-hyun, ended in tragedy when he took his life in 2009 while under investigation for allegedly receiving millions in bribes.

Roh Moo-hyun had promised to root out corruption

When he took office in 2003, Mr Roh had been elected on a promise to root out endemic political corruption but within a year his own actions were under scrutiny. He was suspended and subjected to an impeachment vote over an alleged breach of election rules.

He was later reinstated, but allegations against him emerged again. His relatives, including his wife, admitted receiving payments before his death.

Why so much corruption in South Korean politics?

Many believe the tradition of the South Korean government taking a strong role in leading the economy is one of the major contributing factors.

South Korea's modernisation was only kick-started in the 1960s and 1970s with dictator Park Chung-hee directing the heads of family-run conglomerates known as chaebols to establish industries.

"Until the state steps back from the economy, such scandals will continue." he told the BBC.

Corruption in the family

It is not always the leaders' actions themselves that bring their names into disrepute.

Kim Dae-jung was a Nobel Peace Prize recipient

The country's 15th leader, Kim Dae-jung, an icon of South Korea's democracy movement and a Nobel Peace Prize laureate, saw all three of his sons becoming caught up in political corruption.

The son of the 14th president, Kim Young-sam, also received a sentence for being involved in a loan scandal during his father's presidency.

He himself was interrogated by prosecution officials during his presidency, alongside other members of the government, after they were accused of neglecting their duties during a drastic economic crisis.

Cultural legacies

Professor Kyung Moon Hwang of the University of Southern California points to cultural norms around the idea of social reciprocity causing problems, too.

"[Reciprocity] in general is a good thing, but in the political arena, this can lead to officials expecting something in return for their decisions," he told the BBC.

He explained that because of the lasting legacy of the country's despotism, when bribery was rife, there was a cultural impulse to pay bribes to officials, regardless of whether they wanted them or not, knowing they would feel obliged to return the favour.

This has been a consistent problem - two of the country's first presidents after the assassination of long-ruling dictator Park Chung-hee's assassination were jailed.

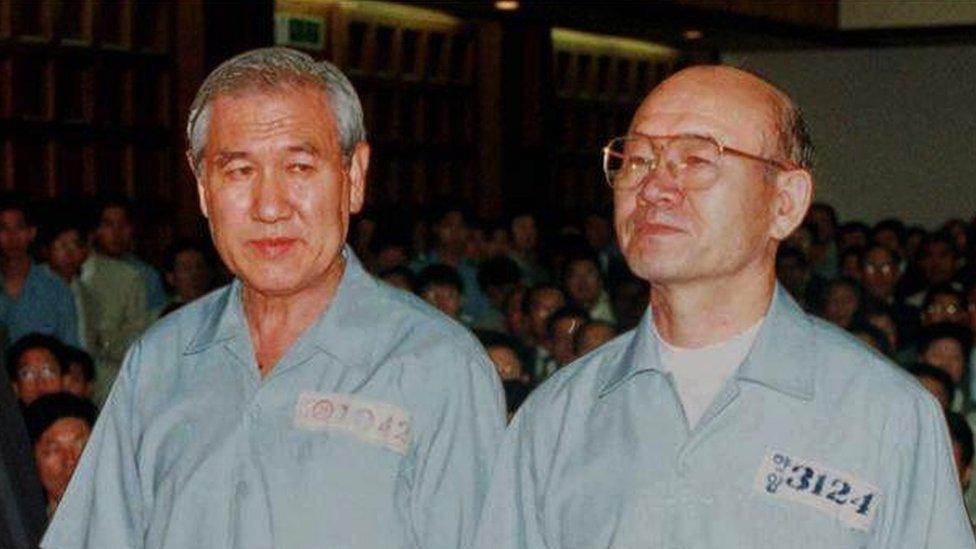

Roh Tae-woo, who served as president from 1988 to 1993, and Chun Doo-hwan, who served from 1979 to 1988, both served time in prison. Chun was originally given a death sentence but the decision was overturned at a later trial.

Roh Tae-woo (Left) and Chun Doo-hwan

It does remain a paradox that a country deemed one of the world's safest should have so many high-ranking politicians charged with criminality.

Reporting by the BBC's Subin Kim.

- Published6 April 2018

- Published31 October 2016

- Published6 April 2018

- Published9 December 2016