Koreas summit: Will historic talks lead to lasting peace?

- Published

Welcoming Kim Jong-un with pomp and ritual

Friday's dramatic meeting between South Korean President Moon Jae-in and his North Korean counterpart, Chairman Kim Jong-un, represents an unambiguous historic breakthrough at least in terms of the image of bilateral reconciliation and the emotional uplift it has given to South Korea public opinion.

Whether the agreement announced at the meeting - the new Panmunjeom Declaration for Peace, Prosperity and Unification of the Korean Peninsula - offers, in substance, the right mix of concrete measures to propel the two Koreas and the wider international community towards a lasting peace remains an open question.

The symbolic impact of a North Korean leader setting foot for the first time on South Korean soil cannot be underestimated.

Mr Kim's bold decision to stride confidently into nominally hostile territory reflects the young dictator's confidence and acute sense of political theatre and expertly executed timing.

The moment Kim Jong-un crossed into South Korea

His clever, seemingly spontaneous gesture to President Moon to reciprocate his step into the South by having him join him for an instance in stepping back into the North was an inspired way of asserting the equality of the two countries and their leaders.

It also, by blurring the boundary between the two countries, hinted at the goal of unification that both Seoul and Pyongyang have long sought to realise.

The rest of the day was full of visual firsts and a set of cleverly choreographed images of the two leaders chatting informally and intimately in the open air - deliberately advancing a powerful new narrative of the two Koreas as agents of their own destiny.

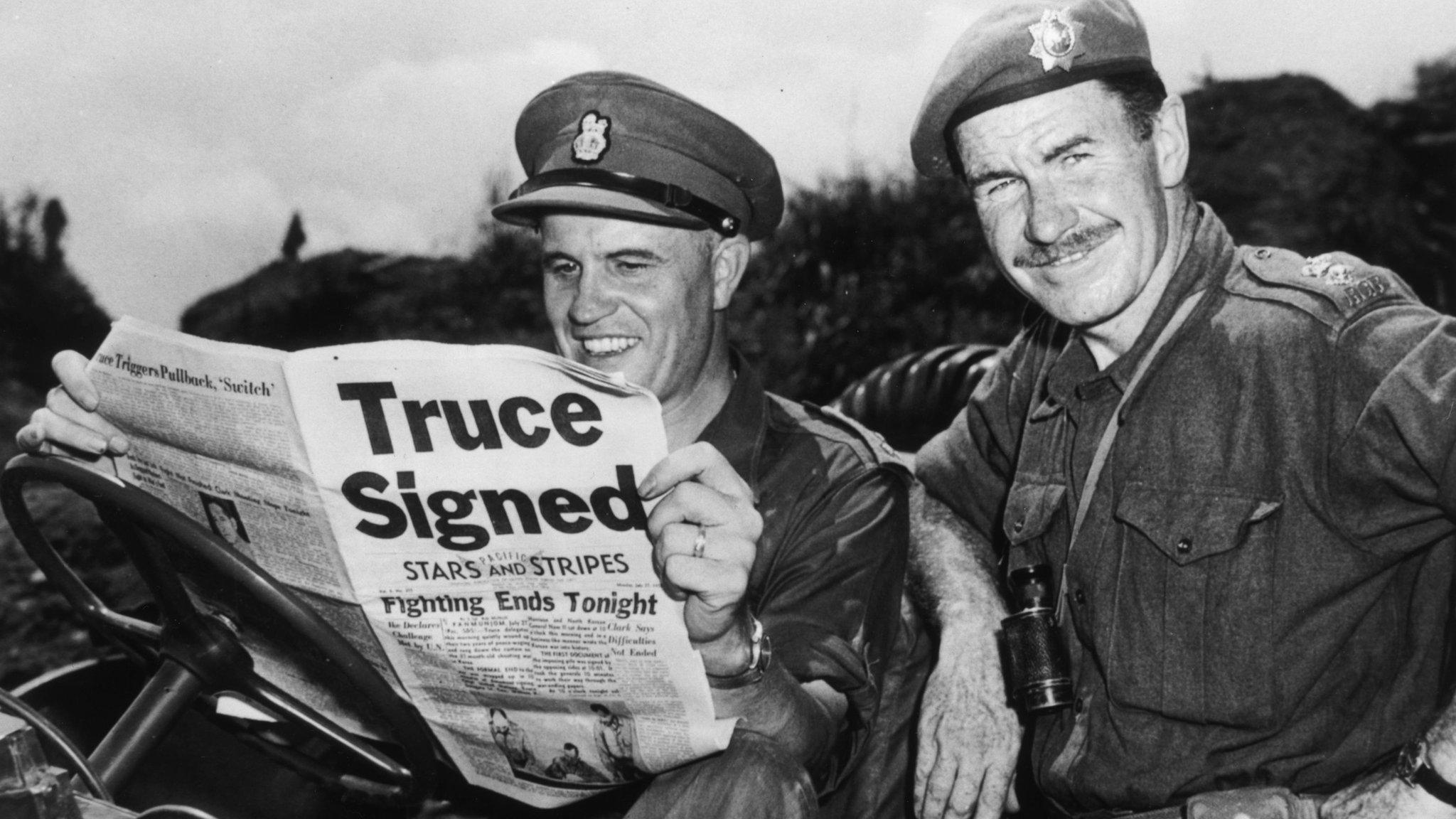

Handshakes, broad smiles and bear hugs have amplified this message of Koreans determining their own future, in the process offsetting past memories of a peninsula all too often dominated by the self-interest of external great powers, whether China, Japan, or more recently, during the Cold War, the United States and the former Soviet Union.

The two leaders' joint statements before the international media were another pitch perfect moment for Mr Kim to challenge the world's preconceptions.

Kim Jong-un issues his pledge for peace with South Korea

In an instance, Mr Kim's confident and relaxed announcement to the press dispelled the picture of a remote, rigid, autocratic leader in favour of a normal, humanised statesman, intent on working to advance the cause of peace and national reconciliation.

A cynic might see this as both a simple propaganda victory for Mr Kim, and also his attempt to lock in place the nuclear and missile advances the North has already achieved by calling for "phased…disarmament" - by intentionally downplaying the expectation of immediate progress while emphasising the need for step-by-step negotiations.

The joint declaration echoes the themes of past accords, including the previous Korean leaders summits of 2000 and 2007, and an earlier 1991 bilateral Reconciliation and Non-Aggression agreement.

Plans to establish joint liaison missions, military dialogue and confidence building measures, economic co-operation, and the expansion of contact between the citizens of the two countries have featured in earlier agreements.

However, Friday's declaration is more specific in its proposals, with the two countries pledging, for example, "to cease all hostile acts against each other in every domain, including land, sea and air…" and providing a series of key dates for the early implementation by both sides of a raft of new confidence building measures.

These include the cessation of "all hostile acts" near the demilitarised zone by 1 May, the start of bilateral military talks in May, joint participation by the two Koreas in the 2018 Asian Games, the re-establishment of family reunions by 15 August, and, perhaps most importantly of all, a return visit to the North by President Moon by as soon as the autumn of this year.

Committing to early, albeit incremental, steps in the direction of peace, appears to be motivated by the Korean leaders' wish to foster an irresistible sense of momentum and urgency.

The declaration also calls for future peace treaty talks involving the two Koreas, together with one or both of China and the US.

The logic of binding external actors into a definite - but evolving - timetable for progress on key issues is that it lowers the risk of conflict on the peninsula - something both Koreas are keen to avoid and which they have long had reason to fear given the past bellicose language of a "fire and fury" Donald Trump.

Playing for time is a viable option, given that President Moon is at the start of his five-year presidency - a marked contrast to the summits of 2000 and 2007, when the respective leaders of the South, Kim Dae-jung and Roh Moo-hyun, were already well into their presidential terms.

Mr Moon can count, therefore, on repeat meetings with Mr Kim, and the two men appear genuinely interested in sustaining their dialogue and making progress on the wide-ranging set of initiatives included in the declaration.

Mr Kim's own statements at the summit have also been a vocal argument in favour of identity politics, given his stress on "one nation, one language, one blood", and his repeated rejection of any future conflict between the Koreas - two themes that will have played well with a South Korean public that traditionally is sympathetic to a narrative of self-confident, although not necessarily strident, nationalism.

President Trump says he will continue to exert maximum pressure on North Korea

For all of the stress on Koreans determining their common future, there is no escaping the decisive importance of the US.

The much anticipated Trump-Kim summit in May or early June will be critical in testing the sincerity of the North's commitment to a peaceful settlement.

Pyongyang's professed commitment to "denuclearisation" is likely to be very different from Washington's demand for "comprehensive, verifiable and irreversible" nuclear disarmament.

Not only will the Trump-Kim summit be a way of measuring the gap between the US and North Korea on this issue; it will also be an important opportunity to gauge how far the US has developed its own strategy for narrowing the differences with the North.

President Moon has cleverly and repeatedly allowed Mr Trump to assume credit for the breakthrough in inter-Korean relations, recognising perhaps that boosting the US president's ego is the best way of minimising the risk of war and keeping Mr Trump engaged in dialogue with the North.

Whatever the long-term, substantive outcome from the Panmunjeom summit, the event has memorably showcased the political astuteness, diplomatic agility and strategic vision of both Korean leaders.

The dramatic events of Friday are a reminder that personality and leadership are key ingredients in effecting historical change, sometimes allowing relatively small powers to advance their interests in spite of the competing interests of larger, more influential states.

Dr John Nilsson-Wright is Senior Research Fellow for Northeast Asia, Asia-Pacific Programme at Chatham House and a senior lecturer in Japanese Politics and International Relations at the University of Cambridge

- Published28 April 2018

- Published27 April 2018

- Published27 April 2018

- Published26 April 2018

- Published24 April 2018

- Published26 April 2018

- Published25 April 2018