The transgender acid attack survivor running for parliament

- Published

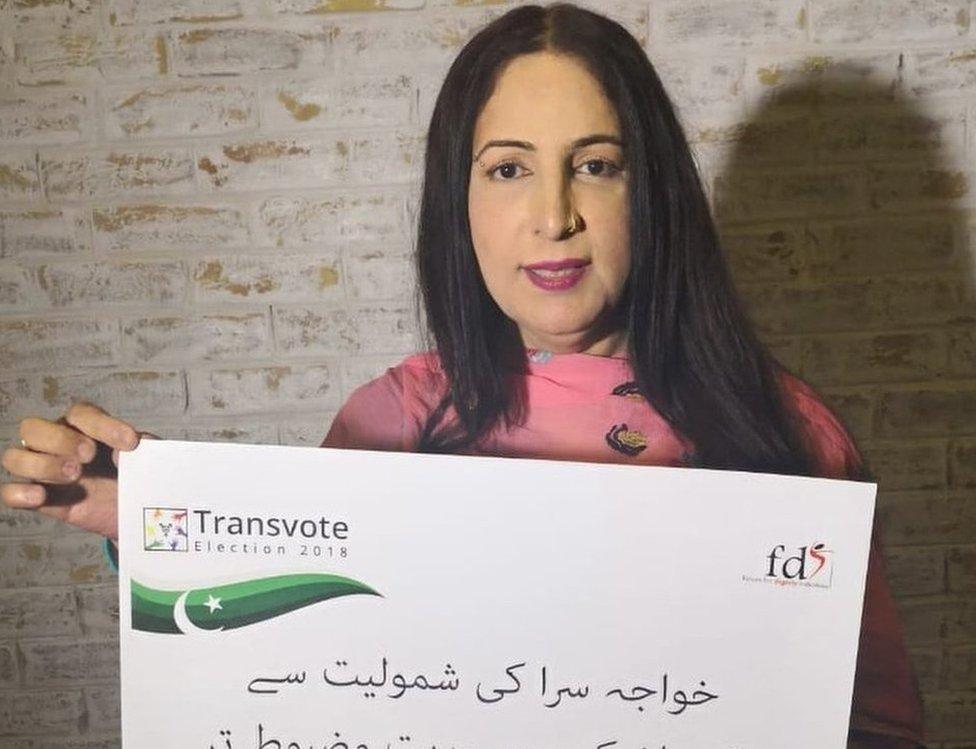

Acid attack survivor Nayyab Ali (L) and Nadeem Kashish are both standing for seats in Pakistan's parliament

Forced to leave home when she was only 13, physically and sexually abused by relatives, and later attacked with acid by her former boyfriend, Nayyab Ali's life as a transgender woman in Pakistan has been turbulent.

But now, the university graduate is one of four transgender candidates standing in Pakistan's general election next week.

"I realised that without political power and without being part of the country's institutions, you cannot gain your rights," she told the BBC.

More people from the community are contesting than ever before, in what has proven to be a significant period for transgender rights in Pakistan.

'Leading in the region'

Shunned and ridiculed by Pakistan's largely conservative society, the transgender community, also known as hijra or khawaja sira, has long been the subject of widespread discrimination and struggled to access basic services such as education, employment and healthcare.

Pakistan's transgender community faces discrimination and marginalisation

During the Mughal empire, eunuchs served as singers, dancers and even advisers in the royal courts. However, when the British colonised India, they vigorously sought to criminalise the transgender community, whom they considered to be deviants, and denied them basic civil rights.

But Pakistan is now "leading in the region" in terms of transgender rights, according to Uzma Yaqoob, founder and executive director of transgender rights group, the Forum for Dignity Initiative.

Pakistan became one of the first countries to legally recognise a third sex on its national ID cards almost a decade ago and extended this to its passports last year, an option which is still not available to transgender and non-binary people in many Western nations.

In May, Pakistan passed new legislation guaranteeing basic rights for its estimated 500,000 transgender citizens - including intersex people, transvestites and eunuchs - and banning discrimination against them.

Marvia Malik, 21, became Pakistan's first transgender newsreader earlier this year

The community is also becoming increasingly visible in public life, with a private TV station hiring its first transgender news anchor in March and a transgender actress making her cinematic debut alongside Pakistan's top film stars last month.

'These days they just kill us'

However, violence and prejudice against transgender people in Pakistan has continued.

Transgender men, on the one hand, are barely visible in the public sphere as a result of the social and cultural expectations of those who are assigned female at birth.

Transgender women, meanwhile, are marginalised by society from an early age and are often forced to dance, beg or engage in prostitution to make a living, leaving them vulnerable to harassment, physical abuse and rape.

Many seek safety with gurus - leaders of small, scattered transgender communities - who give them food and shelter in return for their service and contribution to the group.

"When you leave home, the transgender groups are the only place you feel safe," explains Maria Khan, who ran away after being bullied by her siblings and neighbours at the age of 10. "There no one mocks you, beats you or calls you names, because everyone is like you."

Maria Khan joined a transgender group after leaving home as a child

But many within the community believe that the threats against them are growing.

"Transgender people are being murdered now. There used to be incidents of beating and acid attacks and we were spared, but these days they just kill us," Nayyab says.

According to local activists, almost 60 transgender women have been killed over the past three years in the highly conservative north-western province of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, where the Pakistani Taliban maintained a presence until relatively recently.

One of these women was Alisha, a 23-year-old activist who was shot multiple times by a local gang in 2016. She died without receiving medical treatment after hospital workers spent hours unable to decide whether to admit her to a male or female ward.

'Murdered by their own family'

Maria, from the city of Mansehra, understands these dangers better than most.

She is standing as an independent candidate for the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa provincial assembly and says that hate crimes, or so-called honour killings, are the biggest threat to the local transgender community.

"Our own family hires people to murder us," she explains.

"I barely survived an assassination attempt when shots were fired at my house in Mansehra. There are still bullet holes all over my front door."

Maria is standing in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, where almost 60 transgender women have been killed since 2015

But Maria, who recently graduated from Hazara University, says the local community's response to her decision to run has been overwhelmingly positive, with many donating to her largely self-funded campaign.

She believes that previous politicians "did nothing for the people" and says her first step if elected will be to address a months-long water shortage that has affected her city.

'A game for rich men'

Being able to run is one thing - but winning is something else entirely, as Nadeem Kashish knows.

She is standing against the two frontrunners in the race to become Pakistan's next prime minister: cricketer-turned-politician Imran Khan and the prime minister in the outgoing government, Shahid Khaqan Abbasi.

Nadeem Kashish has been campaigning through her radio programme

Her constituency in the capital Islamabad is one of the most important in Pakistan and is home to the parliament, the Supreme Court and many of the city's most affluent areas.

A transgender rights activist and former makeup artist, Nadeem now hosts her own radio programme on the issues facing her community.

She says that despite the recent legislation, "no political party in Pakistan wants to work on transgender rights, we are not in their agenda. This is the reason I want to run for parliament.

"I don't have a lot of money to spend on banners, flags, transport and other traditional campaigning resources, like these big politicians. I am spreading my message through my radio programme."

Politicians in Pakistan spend huge amounts on their election campaigns, despite the restrictions placed on candidates by the electoral commission.

"Everyone knows it's a game for rich men," says Nadeem. "I didn't even have the money to file my nomination papers."

Nadeem is standing against some of the biggest names in Pakistani politics

Pakistan's Election Commission charges 30,000 rupees (£185; $245) for those running for a seat in parliament and 20,000 rupees for those standing for provincial assemblies.

According to reports, at least eight transgender candidates were forced to withdraw their candidacy due to a lack of funds.

But Nadeem is determined to challenge traditional Pakistani politics.

"This is our time. Only with the participation of transgender people is Pakistan's democratic process complete."

- Published26 March 2018

- Published28 June 2016

- Published23 June 2016

- Published17 May 2017