Thailand cave rescue: What will the impact be on the boys' mental health?

- Published

The moment divers discover the missing boys

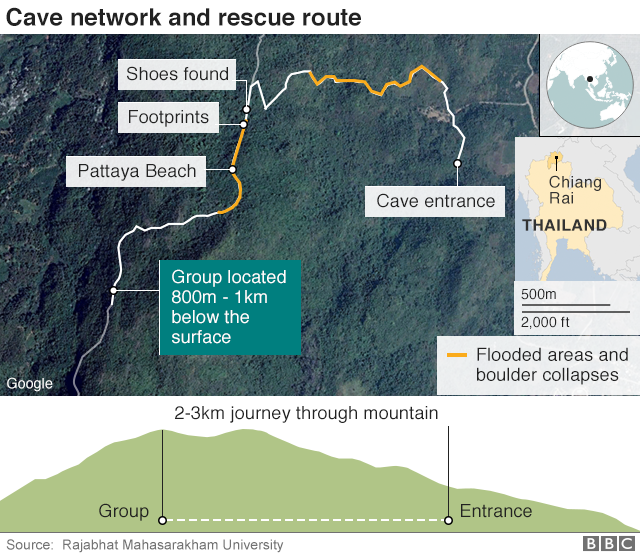

The case of 12 boys and their football coach who were found alive after being trapped in a cave in northern Thailand for nine days has gripped the world.

Rescuers are now trying to work out how to safely get the group out of the cave, with the Thai military warning that the children could be trapped for up to four months.

They have now received food and medical attention, but what will the impact of their ordeal be on their mental health?

Dr Andrea Danese from King's College London is a consultant child and adolescent psychiatrist at the National and Specialist CAMHS Trauma and Anxiety Clinic in London.

He says that in the short term, many of the children facing such a traumatic incident may be fearful, clingy, jumpy or moody.

But he says that the fact that the children are part of a community, in the form of their football team, will have been "protective" in terms of their mental health.

Professor Donelson R. Forsyth, from the University of Richmond in Virginia, agrees.

"Previous cases suggest that the group will draw inward, marshalling its combined resources to survive, for if anyone can survive such a disaster, it is a group - and an organised one at that," he says.

A Facebook photo shows the coach with some of the missing children

Although issues may arise within the group, with emotions such as blame, hopelessness, anger and issues of hierarchy coming to the fore, the group's background as a team may help the boys stay unified, he adds.

What needs to happen now?

This is a highly unusual situation, and even more so because unlike previous incidents such as the Chilean miners, who were trapped underground for almost 70 days in 2010, most of those involved in this case are children.

Dr Danese emphasises the essential role that adults now have to play in helping the children coming to terms with their current situation, from their coach who is trapped with them, to rescue divers and medical staff.

He says that "clear and honest" communication with the children will be essential in minimising any potential trauma.

"It is important that they have information on what is going to happen," he says, pointing out that any unpredictability may increase any negative long-term impact on their mental health.

The children should also be encouraged to speak about their feelings and avoid hiding their emotions.

Contact with their families will also help to raise the boys' morale, and work is already under way to install telephone lines in the cave.

In the meantime, divers are able to keep the group company.

What about the lack of light?

One of the group's major challenges in adjusting to the cave where they are trapped will have been the darkness.

Without enough light to distinguish between night and day, the body clock, or circadian rhythm, "drifts out of sync", according to Professor Russell Foster, chair of Circadian Neuroscience at Oxford University.

This won't just have an impact on their sleeping patterns, as the circadian rhythm also affects mood, gut function and many other areas of the human body.

However, Professor Foster believes rescue teams will try to install lighting within the caves to mimic the night and day cycle, as happened with the Chilean miners.

In addition to preventing jet lag once they return to the surface, the timed exposure to light will help the group to develop a daily routine as far as possible given their difficult circumstances, something Dr Danese says will offer them "some idea of normality".

What will the long-term effect be?

The impact of their experiences in the cave is likely to stay with the children long after their eventual rescue.

Professor Sandro Galea, dean and Robert A Knox Professor at Boston University's School of Public Health, says that children who experience a trauma on this scale "have a high risk of medium to long-term mood disorders", such as depression, anxiety and post-traumatic stress disorder.

This does not mean that all of the boys will develop mood disorders, but he says it would be expected that "a third to a half" of the group could experience mental health issues.

Families of the boys have been celebrating after finding out their loved ones are alive

Of these, a third could experience long-term problems, Professor Galea says, which with the right help is treatable, including with Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) and medication.

But one of the factors that will be most important underground - namely, the group's relationships with each other and the outside world - will play a very significant role in their long-term recovery.

- Published3 July 2018

- Published18 July 2018

- Published3 July 2018

- Published2 July 2018