Why North Korea is in no hurry to do what the US wants

- Published

Meeting in Singapore last month, US President Donald Trump and North Korean leader Kim Jong-un captured the world's attention and promised to work towards "new relations". Why have mixed messages followed?

At the end of a summit billed as an "epochal event", ambitions were set high.

North Korea reaffirmed its commitment to the "denuclearisation of the Korean peninsula", while the US said it would stop "provocative" war games with South Korea.

Things have since taken a rockier path. Although Pyongyang appears to have begun dismantling a rocket site, there have been reports that it is secretly continuing its weapons programme. Meanwhile, Pyongyang has accused the US of "gangster-like" tactics.

So, why has there been a lack of clear progress?

A misfit power

North Korea's notoriety and ability to capture global headlines may have led to its power being overestimated.

It appears Pyongyang has sought to disguise a position of relative weakness as one of unqualified strength. It framed the summit as one between equal nuclear powers.

In fact, the Lowy Institute ranks North Korea 17th out of 25 countries in its Asia Power Index, external - an in-depth assessment of the regional distribution of power, using measures including military, economic and cultural influence.

North Korea is a misfit power. Despite its new-found confidence as a nuclear-armed country, it remains a weak state preoccupied by its very survival.

That its influence is disproportionately dependent on its military strength may, ironically, make it less willing to make serious concessions than the US and others have hoped.

Military capability

North Korea has used the Sohae station to launch rockets

North Korea may be one of the top military powers in Asia, but its emphasis is on quantity over quality.

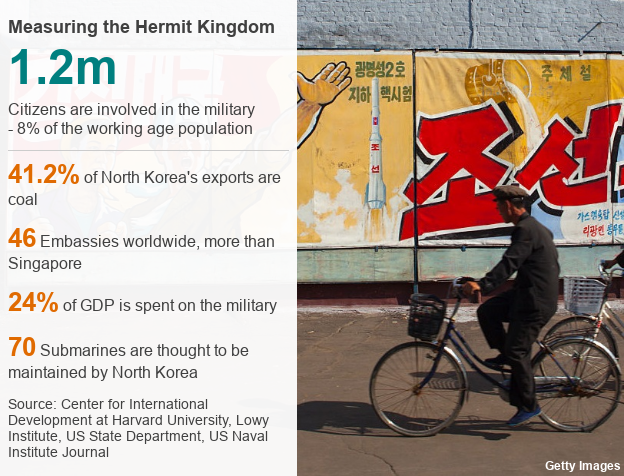

The country's 1.4m military and paramilitary personnel account for about 8% of its working-age population. Only China, Russia and India have larger standing armies.

By comparison, South Korea - which has more than twice the North's population, and compulsory military service - has less than half the armed forces.

Pyongyang has large numbers of battle tanks and even its navy maintains a fleet of about 70 ageing submarines.

But it is its development of intercontinental ballistic missiles and nuclear weapons that enables the regime to make threats far beyond its immediate region.

However, to actually use this capability would be to provoke retaliation that would end the regime.

Siege mentality

Pyongyang's permanent war footing has come at an enormous cost.

The country spends upwards of 24% of its GDP on the military, external, the US Bureau of Arms Control, Verification and Compliance estimates.

This extreme military burden has been justified by invoking a siege mentality among its population, with chronic impoverishment explained away as the result of the actions of foreign aggressors.

The consequence is that, on all non-military measures of resources and influence, North Korea is flatlining.

Economic resources

A coal power station in Pyongyang

In a dynamic and rapidly growing part of the world, North Korea is falling behind.

North Korea's economy, when local prices are taken into account, is roughly the same size as that of Laos, one of the poorest countries in south-east Asia, which has just a quarter of the population.

The productivity of North Korea's workers is the lowest in Asia, external and it suffers from an unusually low share of natural resources.

The country relies substantially on imports of food, refined metals and fuel, while its main export to the outside world is coal briquettes, external.

Diplomatic networks

Pyongyang's diplomatic and economic relationships are similarly stunted.

Its trade with the region in 2015 amounted to about $6bn, less than 1% of South Korea's total, Lowy Institute research suggests, external.

And yet it does have links with a surprising number of countries.

Pyongyang maintains a network of 46 embassies worldwide, external, just behind New Zealand, and ahead of many other countries, including Singapore.

These outposts have often been accused of operating as fronts for illicit activities.

Chinese lifeline

North Korea also makes the best of the few friends it has.

Simply existing next to China benefits North Korea. A mutual defence treaty commits each country to providing military assistance to the other should it be attacked.

Economically, Beijing is a lifeline, with trade between the two countries accounting for 87% of North Korea's total trade, according to research by the Lowy Institute.

That gives Beijing tremendous power to impose costs on Pyongyang if it so wishes.

Yet North Korea knows that while China has supported UN sanctions, it is likely to steer clear of more punishing measures.

That would risk the collapse of the regime and cause instability on its border.

International influence

North Korea is a wily survivor, but that is not the same as having broad-based international power.

Indeed, it suffers from what has been described as a "legitimacy deficit", external, particularly when compared with larger, more democratic and more prosperous South Korea.

Like its southern counterpart, North Korea claims to be the legitimate government of the entire peninsula.

But it has much less power than its neighbour.

South Korea also has a formidable military and its treaty alliance with the US includes extended nuclear deterrence.

It wields widespread influence in Asia, with well-developed trade and investment ties.

And it has cultural power to match - partly through a voracious regional appetite for K-pop and South Korean soap operas.

South Korea attracts 15.7 million tourists annually from across Asia, compared with the estimated 1.4 million Chinese tourists that visit North Korea each year.

What happens now?

North Korea receives only a fraction of the tourists welcomed by South Korea each year

By drawing the US president into talks - and partially normalising ties - Mr Kim appears to have played a weak hand well.

He praised Singapore's economic success and promised to bring home lessons for North Korea's progress. But he did not agree to a timeframe for denuclearisation.

The US wants North Korea to give up its nuclear weapons upfront and reap largely economic rewards in return.

Yet it is far from clear that Pyongyang sees economic development as being incompatible with keeping some form of nuclear power.

And its willingness to give up its signature weapons capabilities is likely to depend on whether it thinks reforming into a benign state would risk the collapse of the regime.

Even if it felt it could survive, North Korea might well have to submit to being South Korea's junior partner.

It would be decades before income reaches levels seen in South Korea and with only half the population, it would be likely to remain in its shadow.

Is that too steep a price for the Kim dynasty to pay?

About this piece

This analysis piece was commissioned by the BBC from experts working for an outside organisation.

Hervé Lemahieu is director of the Asian Power and Diplomacy Program, external, at Australia-based international policy think tank the Lowy Institute. Follow him @HerveLemahieu, external.

Edited by Duncan Walker