Imran Khan: Can former cricket star change Pakistan?

- Published

Imran Khan captained the Pakistan cricket team to a World Cup victory in 1992

Imran Khan, a former star cricketer, has been elected Pakistani prime minister two decades after he first entered the political arena.

This is the climax of a career that began in the 1970s for a man once widely seen in the West, and particularly in the UK, as an Oxford-educated playboy, as at home in London's nightclubs as he was at the batting crease.

In the West, writes Jonathan Boone, a former Pakistan correspondent for the Guardian, his politics are still "presumed to be as liberal as his private life".

The coming months and years will determine if that's true.

Promise of change

He started his political career in the late 1990s, still basking in the glow of having led Pakistan's cricket team to a World Cup win in 1992. But it took a further two decades for him to become a serious contender for power.

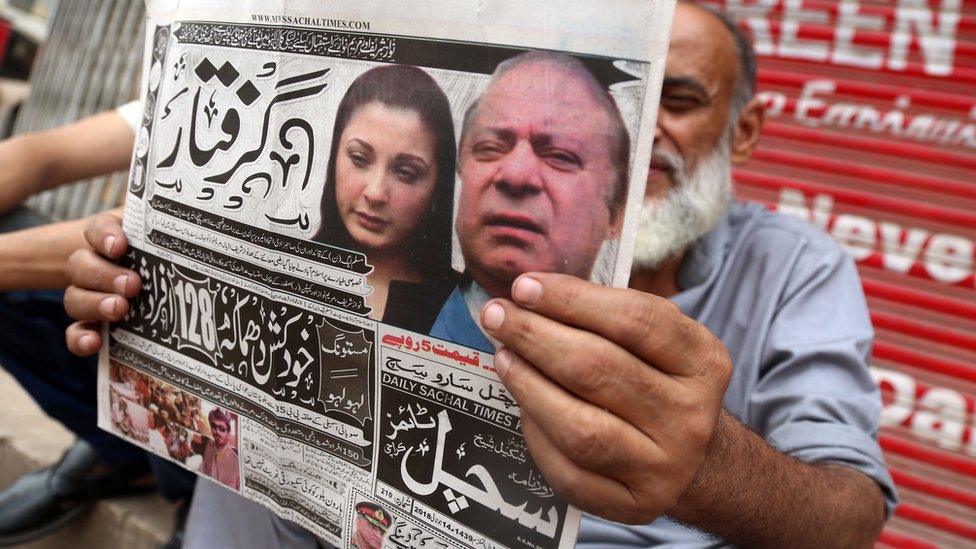

In 2013, his Pakistan Justice Movement (PTI) party emerged from obscurity as the third largest political force, after former Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif's Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz (PML-N) and former president Asif Zardari's Pakistan People's Party (PPP).

So for Mr Khan, and many of his followers, this is a dream come true.

Five things to know about Imran Khan (from 2018)

He brings with him the promise of change; improved education and health facilities, and more jobs for young people - who constitute nearly 64% of the country's population and provide the bulk of Mr Khan's electoral support.

He seems to be comfortably placed to make this happen. With his tally of parliamentary seats, he will be able to muster the required majority by attracting independent candidates instead of having to make uncomfortable alliances with organised parties.

His initial challenge as prime minister will be to gain legitimacy - he is seen by critics and rivals as a proxy of the country's powerful military establishment, which they say manipulated the electoral process to propel him to power.

Mr Khan is also accused of undermining democracy by conducting a vicious five-year-long campaign against Mr Sharif - who was ousted as prime minister by the Supreme Court last year - despite the fact that Mr Sharif's election in 2013 was seen by domestic and international observers as largely free and fair.

But this is only half of the problem.

Blow to dynastic politics

Observers say Mr Khan's most significant challenges are likely to flow from his rather simplistic notion of what actually ails Pakistan. This is apparent from what he has been telling his followers in recent years.

Young voters have provided the bulk of Mr Khan's electoral support

Mr Khan says the only way he can fulfil his promise of job creation and improved services is by dealing a death blow to dynastic politics - his two chief rivals, the PML-N and PPP parties, have alternatively held power during democratic interregnums since 1988 - and by catching corrupt leaders and making them cough up stolen wealth.

He has shown no inclination to distinguish between undiluted democracy and a democratic facade dominated by a military that seeks to control the country's security and foreign policies, and that runs a huge business empire of its own.

He has also not indicated that he sees religious militancy as a problem.

Military strength

Many believe that in the medium term he may find himself on a collision course with the military establishment, as has been the experience of his two predecessors.

This is because once he assumes power and takes sight of the bigger picture, veteran political observers say, he will find that the route to improving health and education, and to creating jobs and triggering the economic growth that Pakistan needs, passes through territory appropriated by the military.

Like his predecessors he will realise, they say, that he must first reduce conflict and tension in the region, especially with India, where such issues are widely blamed on Pakistan's security establishment.

He will also have to reform the country's bureaucracy and judiciary, and ensure and reinforce the writ of the government in areas ceded to rent-seeking business interests often allied with the military.

But having drawn many of those rentier-capitalists to his party's fold in the run up to elections, he may not find it an easy target to achieve.

A failure to rein in the army would also hurt the country's international standing.

It already faces aid restrictions from Washington, hitherto the country's main source of security and development funding.

And it has been included on the watchlist of an international terror-financing watchdog, the Paris-based Financial Action Task Force (FATF), which carries further implications for its international funding.

The country is already in a financial crisis - its foreign debt has ballooned and its currency is in freefall.

Interestingly, just as it was being greylisted by FATF in late June, the country lifted restrictions on a host of internationally wanted militant leaders to contest the election, reportedly under a military-sponsored policy of the "mainstreaming" of militants.

This has not gone down well with either Delhi or Washington, but unlike his top political rivals, Mr Khan avoided raising this issue during his election campaign.

Khan's options in power

Analysts say he is likely to end up walking one of two possible routes.

He may find a way to work with rival parties like the PML-N and PPP - the ones who have the distinction of having seen the reality of Pakistan from the high seat of power and who are now poised to raise a formidable opposition front, given their combined parliamentary strength, which is not much less than that of Mr Khan and his PTI.

Since his decade of political campaigning has focused on casting these two parties as the chief enemies, however, this may take some nerve.

The other option is to govern with his youthful followers under the country's continuing system of controlled democracy. In that case, he may sit back and enjoy the position while the going is good.

- Published26 July 2018

- Published1 February 2024

- Published25 July 2018

- Published22 July 2018

- Published25 July 2018