'Children jailed as adults' seek justice from Australia

- Published

Abdul says he was a child when he was jailed by Australia for people smuggling

More than 120 Indonesians who say Australia wrongly jailed them as adults - when in fact they were children - have launched a bid for compensation.

The BBC's Indonesia editor Rebecca Henschke visited remote Rote Island to hear how they became caught up in human trafficking.

Siti Rudy's eyes fill with tears when she recalls the long months in 2009 when, with no news, she assumed her son Abdul was dead.

"I cried and cried because as the youngest he was the one who looked after me," she says, sitting on the cement floor of her home, a one-bedroom house in Oelaba village on Rote, the Indonesian island closest to Australia.

"After a long time he called me and told me he was in jail in Australia. That was a very hard thing to hear."

Siti Rudy (right) thought she had lost her son, Abdul, at sea

Abdul says he unwittingly became, in the eyes of the Australian authorities, a people smuggler, carrying asylum seekers into Australian waters.

He says he was offered around $100 (£77), a significant amount of money in this area, to work on a boat transporting rice. He didn't know or ask where it was going.

Australia intercepts any boats attempting to bring refugees or asylum seekers to its shores.

Under Australian policy at the time, any crew members of those boats found to be children should have been returned home - rather than face charges.

But Abdul was convicted as an adult and jailed for two-and-a-half years. His family and village officials say he was just 14 at the time.

Abdul says he was offered about $100 to work on a boat that left Indonesia

"I was scared I would be beaten up," he says.

"I was so far from my family and held for a long time. That's what was frightening but I got used to it after a while," he says.

I have interviewed many men in Abdul's position over the years - they all go very quiet when they talk about their time in jail. Lawyers say several children were physically and sexually abused, and still suffer psychological trauma.

Lawyers in town

Siti's small house is a hive of activity. Giggling children crowd around the veranda as a group of Australian lawyers take down her story.

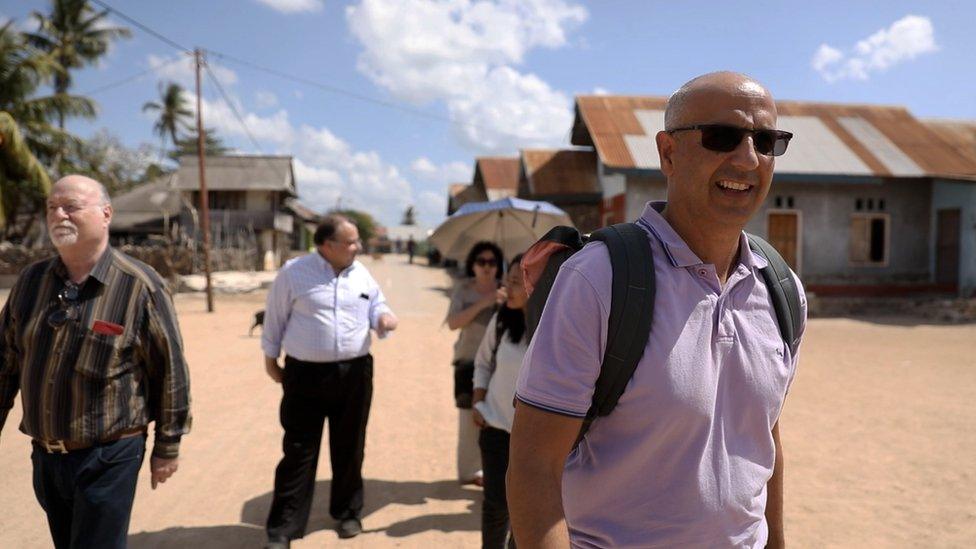

Australian lawyers are seeking compensation through the Australian Human Rights Commission

Among the visitors, Mark Barrow of Ken Cush Associates is building up a case to have Abdul's conviction overturned and to fight for some form of compensation.

More than 120 boys who were imprisoned between 2009 and 2011 have signed up for the class action, pursuing compensation through the Australian Human Rights Commission.

They are seeking money from the Australian Federal Police, Australia's Commonwealth Director of Public Prosecutions and the doctor who used a now-discredited X-ray method to determine their age.

A 2012 report by the Australian Human Rights Commission, external entitled An Age of Uncertainty found numerous breaches of the boys' rights.

Lawyer Mark Barrow with Siti at her home in Rote

"If this was an Australian child, you would expect the Indonesian police to ring up their parents and ask for the details, and quickly their child would be sent back to Australia. This didn't happen," says Mr Barrow.

"I think most people would fairly agree that if that happened to their children, then they would seek redress."

The whistleblower

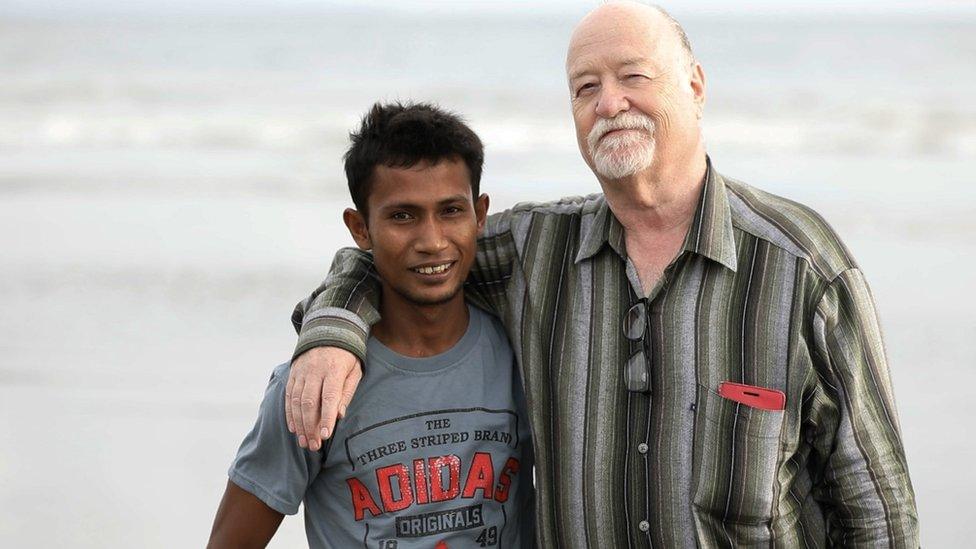

Colin Singer was an independent prison visitor, a volunteer job he had held for around four years, when he came across the Indonesian boys behind bars.

"There was this tiny kid holding on to this barbed wired fence and I remember saying to him gently, 'what's your name?' And he was in tears, clearly traumatised."

Mr Singer started asking questions, but says appeals to resolve the matter with Australian and Indonesian authorities fell on deaf ears.

Colin Singer (right) with Ali Jasmin, who was freed in 2012 after drawing extensive media coverage

"I strongly believe that the Commonwealth of Australia knowingly and willingly imprisoned these children," he says.

"It's beyond belief that a single child could end up in adult prison - not for a day, not for a week, but for nearly three years - and we are not just taking about one child here."

As for Indonesia, he says: "The government didn't want to do anything. They didn't provide lawyers. They didn't provide any assistance whatsoever. I was appalled."

The lead claimant

The boy Mr Singer met behind bars that day was Ali Jasmin.

Documents, including an Indonesian birth certificate showing he was 13 at the time of his arrest, were obtained by the Indonesian government but never tendered in his defence.

"I kept arguing that I was a child, but I was sentenced to three years because they said I was an adult," he says.

"I was angry that the test they used was not my mum; it didn't give birth to me."

"My battle for justice was worth it," Ali Jasmin says

Ali Jasmin was released in 2012, after extensive media coverage of his case, and deported back to Indonesia.

Last year he became the first boy to have his conviction overturned in Western Australia's Court of Appeal, which found that a "miscarriage of justice" had occurred.

"My battle for justice was worth it," he says.

Mr Singer, he says, has become like family for him.

"What I am fighting for now is compensation for the time I spent in jail," Ali says. "After that I will give money to my parents. I want to make my family happy."

He has a two-year-old daughter and works as a fisherman. Having not been able to complete his high school education, jobs are scarce.

What Australia and Indonesia say

The 2012 Australian Human Rights Commission report found numerous breaches of the boys' rights, and flawed handling of their cases.

It stated that "federal police and the CDPP [Australia's Commonwealth Director of Public Prosecutions] placed reliance on wrist X-ray analysis as evidence that a person was over the age of 18 years - despite significant material being available to support the conclusion that they should not do so."

The CDPP and Australia's foreign affairs department turned down the BBC's requests for interviews.

The CDPP said via email: "You are aware there are still active legal proceedings and as such we decline the offer to be interviewed or provide any comment."

Rote is an Indonesian island about 500km (300 miles) from Australia

Dede Syamsuri was Indonesia's consular-general in Perth at the time. Now ambassador to Morocco, he says Indonesia was not in a position to help most of the boys.

"[This was] simply because we had nothing in our hand - we had no proof of how old the boys were," he says.

He says Indonesian authorities were able to help just two, or perhaps more, boys - including Ali Jasmin. In those instances, Indonesia helped the boys get documents from their families to prove they were children.

Once those documents were handed over to lawyers appointed by Australia, Dede Syamsuri says Indonesia left the matter with the Australian courts.

"Because those responsible were doctors using medical ways [to determine ages], I just had to agree with what they said. We had to accept what the doctor found," he says.

"Indonesia did firmly raise the issue of the underage boys with Canberra." But he adds: "It was very hard to discuss further the issue."

Anger over inaction

Ali Jasmin says he felt deeply let down by Indonesia.

"I am disappointed and angry because they should have been fighting for us," he says.

"They should have been our biggest defenders but they just weren't. The Indonesian consular [officials] asked us if we were underage and we told them clearly that we were, but nothing changed."

Children play on a beach in Rote

Dede Syamsuri says Indonesian officials regularly visited the boys in jail, bringing them religious books and food.

"Of course being in jail wasn't fun but I saw that they were happy," he says.

"They could do regular exercise because there was a basketball court, football pitch and they had a room just for watching TV. The facilities were very good and they enjoyed them. The jails are very different to ones we have in Indonesia."

He says he did receive reports that some boys were being sexually harassed, and he requested that the boys be moved to other jails.

Dede Syamsuri says he was surprised and pleased to hear from the BBC that Ali's conviction had been overturned.

Too sick to go home

For Erwin Prayoga, who shared a cell with Ali Jasmin, this legal battle comes too late. He died about two months after being released and sent home to Rote Island.

Erwin's family says he was 14 when he was arrested by Australia.

His younger brother, Baco Ali, breaks down when he tells me about the excruciating pain Erwin was in before his death.

Baco Ali (pictured) wants justice for his brother, Erwin Prayoga

"It's hard to remember how sick he was," Baco Ali says through tears.

"They had to push him in a wheelbarrow to the local health centre. I have been told by the lawyers that if you are not well then you shouldn't be sent home from Australia. I want to know why he was."

Lawyers have obtained his medical records in Australia and are asking the same question.

Erwin's family lack the means to make him a "proper" grave

Erwin's family say any compensation they receive will be used to make him a proper grave.

Now it's marked simply with rocks and a wooden block at the back of their house, near the fishing boats where Baco Ali comes to pray often.

Lawyers say more avenues are available through the courts, if compensation is not achieved through the Australian Human Rights Commission.