The asylum detainee who shot a film in secret

- Published

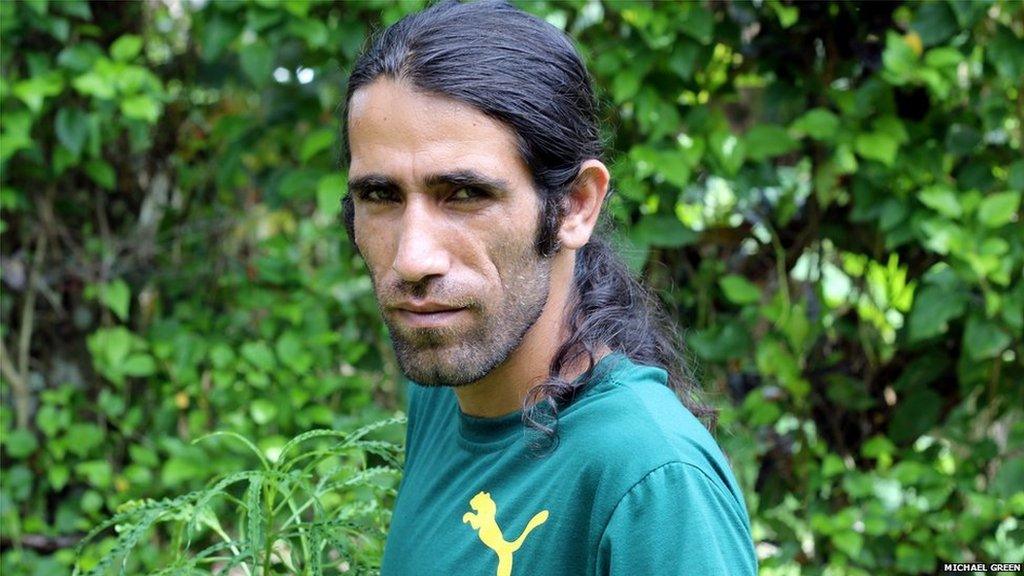

Behrouz Boochani has been on Manus Island for four years

"I think art is life, and I believe in a kind of art that comes from life and experience."

Behrouz Boochani is messaging me on WhatsApp from Australia's offshore detention facility in Manus Island, Papua New Guinea (PNG), where he has been since 2013 after fleeing his home country of Iran.

The Kurdish journalist has just finished his biggest project yet - a full-length feature film, shot using his iPhone and smuggled out over the internet in small clips, beneath the radar of his guards.

"The movie is a record of Australian history. I hope that the next generations will know what Australia did in Manus and Nauru," he says, referring to Australia's other offshore detention facility for asylum seekers.

The project began last year, when Dutch-Iranian filmmaker Arash Kamali Sarvestani got in touch with Mr Boochani, who has made a name for himself as the island's most outspoken detainee, writing regularly for international publications.

Mr Sarvestani had attended a film workshop where the theme was the sea, and he had been looking into the possibility of speaking to children on Nauru.

He quickly realised that access to Nauru was too difficult.

Mr Sarvestani wanted to show the "invisible violence" at the centre

"There is almost no internet connection, and people are scared to talk. They are scared for their future," he says.

That was when he started reading online about Mr Boochani, who he said seemed to be "shouting about what is happening" on the two islands.

'Lost meaning of time'

Since it opened, the Manus Island facility has made headlines with riots and hunger strikes, including images of asylum seekers sewing their lips shut. But Mr Sarvestani's aim was not to show those kind of extremes.

"I wanted to show a painting, about what was happening there… I didn't want to show blood, the violence. I wanted to show the invisible violence within the camp," he says.

The idea was to film everyday scenes of the facility, to portray the agony of the mundane and the psychological suffering when one has no control over their future - the "invisible violence" Mr Sarvestani talks about.

"People [on Manus] are just losing their minds. They have lost the meaning of time," he says.

Over six months, the two men communicated over WhatsApp, recording and sending audio messages to one another, though never speaking directly.

Mr Boochani, left, in a scene from the film

"The internet wasn't strong enough to talk, but it was possible to send audio," Mr Sarvestani says. "That was vital to the project. We needed to listen to each other."

Mr Boochani had an iPhone that an Australian friend sent to him, and some connectivity on the island, but he had never filmed anything before.

He was guided by Mr Sarvestani at first, who told him which shots he was looking for.

He then sent the footage over WhatsApp, but the internet was very slow, and it could take one to two hours to send 30 seconds of video.

The covert nature of the project made it highly stressful for Mr Boochani.

"To take some of the shots I had to wait for several days until I had the opportunity to do it secretly, and I could only ever do one take," he says.

"As a journalist the system is always monitoring me, and I had to be careful because if the guards knew that I was making a movie they definitely would have stopped me.

"But now that I've done it, what can they do? Nothing."

Accommodation inside the Manus Island detention centre

The 88-minute film is called "Chauka, Please Tell Us The Time", after a bird native to Manus that starts singing at the same time every morning. "Chauka" was also the name given to the detention centre's solitary confinement area.

The two men have become great friends over the course of the film-making, after what Mr Sarvestani said amounted to "around 10,000 minutes" of indirect conversation.

"It's one of my dreams to one day meet him," he says.

Uncertain future

The filmmaker holds hope that day will come, but there is no certainty.

Mr Boochani fled Iran after his work as an editor of a magazine, Werya, attracted the attention of authorities, who were unhappy with its promotion of Kurdish culture and politics.

When his colleagues were arrested in February 2013, Mr Boochani went into hiding. Later he tried to make his way to Christmas Island, an Australian territory in the Indian Ocean.

The centre is set to close, but it is unclear what will happen to detainees

The same year, Australia did a deal with PNG, offering around A$400m (£235m; $300m) in aid if it agreed to house the detention centre and resettle refugees.

The Australian government said it made the decision to deter people-smuggling boats and thereby prevent deaths at sea.

Australia is now hoping the US will take up to 1,250 refugees from Manus and Nauru, so it can close the Manus centre by November after a PNG court ruled it was unconstitutional.

But with information so tightly controlled, it is unclear how many will go, and when. And if the deal goes to plan, there are questions over what happens to asylum seekers left in PNG.

Meanwhile, tensions are rising between locals, the police and those in the centre.

Last week multiple shots were fired and a group, including members of the Papua New Guinea defence force, stormed the facility.

Amnesty International called for an investigation.

Mr Boochani says PNG police believe his work is aimed at them, but he insists it is not.

"It is not just for refugees but for Manusian people," he says. "They will know how I respect their culture by watching this movie".

Screenings of Chauka, Please Tell Us The Time will be held later this year in Australia