Myanmar Rohingya: Why Facebook banned an army chief

- Published

Facebook is undoubtedly one of the biggest social media platforms in Myanmar

A number of high-profile army figures in Myanmar, including the army chief, no longer have Facebook accounts.

Facebook cancelled their accounts after a UN report called for several leaders to be investigated and prosecuted for genocide over their role in violence against the Rohingya minority and others.

It's the first time Facebook has banned any country's military or political leader.

In all, Facebook has removed 18 accounts linked to Myanmar and 52 Facebook pages., external One account on Instagram, which Facebook owns, was also closed.

Between them they were followed by almost 12 million people.

Facebook is one of the biggest social media platforms in Myanmar (also called Burma), with more than 18 million users.

The UN report said that for most users in Myanmar "Facebook is the internet" but that it had become a "useful instrument for those seeking to spread hate".

What was in the UN report?

Its wording was the strongest UN condemnation so far, external of the military's operations against the Rohingya.

The military launched a crackdown in Rakhine state last year after Rohingya militants carried out deadly attacks on police posts.

Thousands of people have died and more than 700,000 Rohingya have fled to neighbouring Bangladesh. There are also widespread allegations of human rights abuses, including arbitrary killing, rape and burning of land.

The report named six senior military figures, including Myanmar's top commander Min Aung Hlaing, who it said should be investigated for genocide, and called for the case to be referred to the International Criminal Court (ICC).

The report had begun its investigations months before the latest crisis, which it said had been "a catastrophe looming for decades".

Who are the Rohingya and why are they so hated?

The Rohingya are one of many ethnic minorities inside Myanmar and make up the largest percentage of Muslims - but they are not officially classed as Burmese citizens.

The government sees them as illegal immigrants from neighbouring Bangladesh, which also denies them citizenship.

Many Rohingya have set up refugee camps in nearby Bangladesh

Even the term "Rohingya" is controversial and many in Myanmar avoid using it, instead calling them "Bengali", which reinforces the notion that they are immigrants from Bangladesh.

They have mostly lived in Myanmar's under-developed Rakhine state, competing for resources with other struggling ethnic groups who feel they are the true Burmese.

The UN report said that over the years, government and military actions against the Rohingya had resulted in "severe, systemic and institutionalised oppression from birth to death".

The state newspaper has used words like "fleas" to describe them.

Buddhist nationalist groups have also pushed the idea that Rohingya Muslims are a threat, seeking to turn the country to Islam.

What do people say online about the Rohingya?

Comments describe the Rohingya as dogs, maggots and rapists. Others suggest that they be fed to pigs.

Some outright condemned Islam, with one Facebook page in Burmese calling for "genocide of all Muslims".

The BBC's Facebook posts about the Rohingya attracts similar levels of vitriol. Monday's story of the UN report led to multiple comments on the post condemning the Rohingya.

"The Rohingya are Bengalis... they are invaders," said one. "They eat Bengali food, speak Bengali, wear Bengali dress. Burmese people should drive every last Bengali back to Bangladesh."

What about the army chief?

Min Aung Hlaing is a hugely influential figure in Myanmar

Army chief Min Aung Hlaing had two Facebook accounts.

According to AFP news agency, one account had 1.3m followers and the other 2.8m followers - a substantial following. His position also means he wields a huge amount of influence.

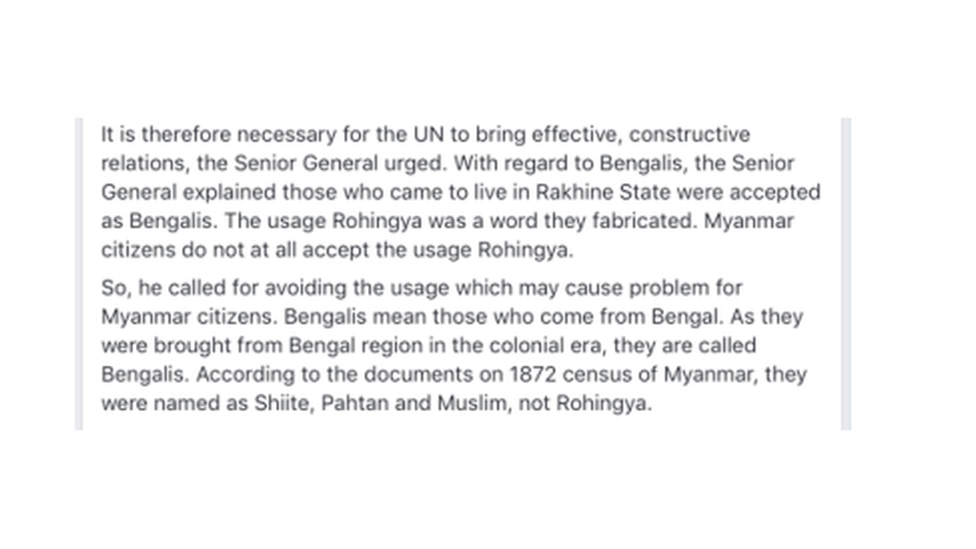

In a Facebook post, he too referred to Rohingya as "Bengali", saying that Rohingya was a "fabricated" word.

Facebook said his page - along with other banned pages - had "inflamed ethnic and religious tensions."

An excerpt taken from Min Aung Hlaing's Facebook post

According to news site the Myanmar Times, presidential spokesperson U Zaw Htay said that the decision to ban the accounts was made without consulting the government.

He added that they were "in talks with Facebook to get the accounts back".

What has Facebook done?

Nothing until now.

This issue is not a new one. In 2014, experts raised the alarm about Facebook's role in spreading hate speech in Myanmar.

In March, a UN official said Facebook had "turned into a beast" in the country.

The report said Facebook had been "slow and ineffective", in tackling hate speech. The "extent to which Facebook posts and messages have led to real-world discrimination and violence must be independently and thoroughly examined," it said.

Facebook agreed on Tuesday that it had been "too slow to act", but that it was "making progress - with better technology to identify hate speech, improved reporting tools and more people to review content".

Facebook also acknowledged that many in Myanmar relied on the platform for information, "more so than in almost any other country".

- Published27 August 2018

- Published27 August 2018

- Published23 January 2020

- Published11 September 2017