Japan says it's time to allow sustainable whaling

- Published

Whales are known to be intelligent and sociable animals

Few conservation issues generate as emotional a response as whaling. Are we now about to see countries killing whales for profit again?

Commercial whaling has been effectively banned for more than 30 years, after some whales were driven almost to extinction.

But the International Whaling Committee (IWC) is currently meeting in Brazil and next week will give its verdict on a proposal from Japan to end the ban.

Don't the Japanese already kill whales?

Yes, they do - but it's complicated.

IWC members agreed to a moratorium on hunting in 1986, to allow whale stocks to recover.

Pro-whaling nations expected the moratorium to be temporary, until consensus could be reached on sustainable catch quotas.

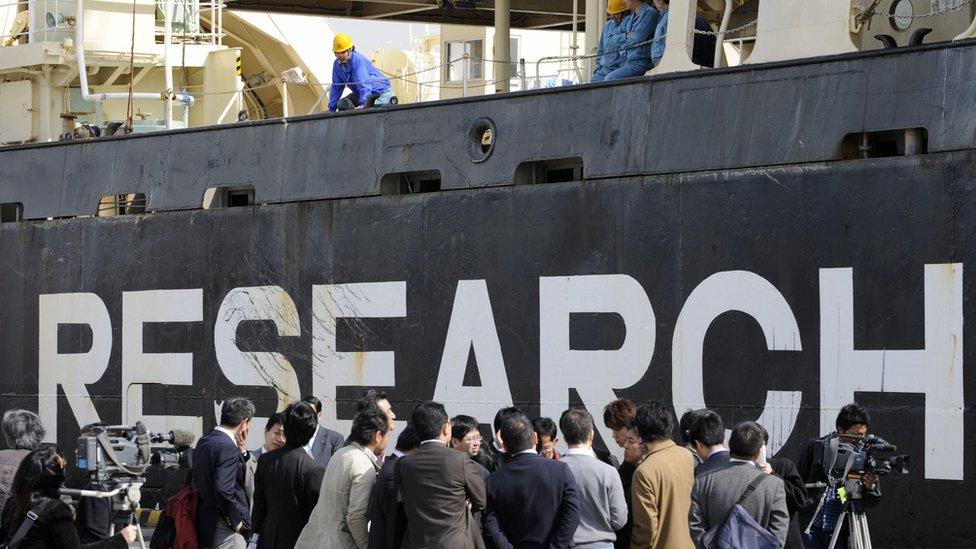

Japan used a clause allowing scientific whaling to continue its hunt

Instead, it became a quasi-permanent ban, to the delight of conservationists but the dismay of whaling nations like Japan, Norway and Iceland who argue that whaling is part of their culture and should continue in a sustainable way.

But by using an exception in the ban that allows for whaling for scientific purposes, external, Japan has caught between about 200 and 1,200 whales every year., external since, including young and pregnant animals.

Among other things, it says it's investigating stock levels and to see whether the whales are endangered or not.

Critics say this is just a cover so they can kill whales for food. And in fact, the meat from the whales killed for research usually does end up for sale.

What's Japan's proposal?

Hideki Moronuki, Japan's senior fisheries negotiator and commissioner for the IWC, told the BBC that Japan wants the IWC to get back to its original purpose - both conserving whales but also "the sustainable use of whales".

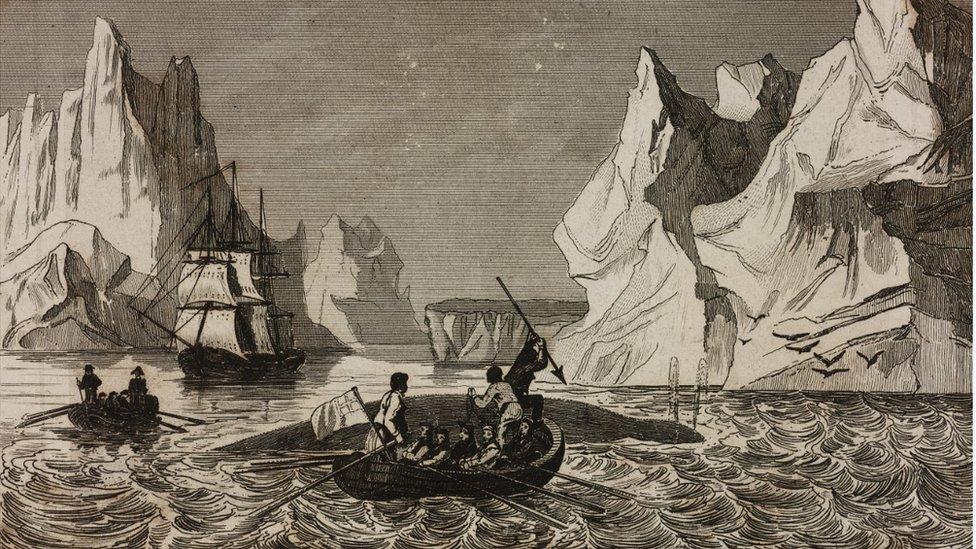

Whaling in the 19th and early 20th Century brought the giant mammals to the brink of extinction.

By the 1960s improved catch methods and giant factory ships made it obvious that whale hunting could not go unchecked. Hence the moratorium.

Japan kills 300 to 400 whales each year

Today, whale stocks are carefully monitored, and while most species are still endangered, others - like the minke whale which Japan primarily hunts - are not.

So Japan, the current chair of the IWC, is suggesting a package of measures, including setting up a Sustainable Whaling Committee and setting sustainable catch limits "for abundant whale stocks/species".

As an incentive to anti-whaling nations, the proposals would also make it easier to establish new whale sanctuaries.

But isn't whaling just... wrong?

Not everyone thinks so.

Anti whaling activists are of course up in arms about the proposal.

Many whales are endangered, minke whales however are not

"These graceful giants face so many threats in our degraded oceans such as entanglement, plastic and noise pollution, and climate change, the last thing they need is to be put back in the whalers' crosshairs," says Kitty Block, president of Humane Society International.

There's also the argument that whales are very intelligent animals with highly developed social structures. Killing them causes them fear, panic and pain.

The old way of whaling with a plain harpoon meant a slow and agonising death.

Modern hunters though aim to kill the animal instantly, usually with an exploding harpoon, but conservations argue it can still take very long for a whale to die.

Traditional whaling often resulted in a drawn-out death for the animal

Two years ago the Australian government released graphic footage from 2008 showing a Japanese research ship harpooning a whale which activist group Sea Shepherd said took more than 20 minutes to die.

"And that's not to mention that they are killing them with their family members, with their pods having to witness their family members screaming out in pain," says Jeff Hansen, managing director of Sea Shepherd in Australia.

Those in favour of whaling say such cases are exceptions - accidents that also happen in any abattoir.

Yet their main point is that they argue that opposition to sustainable whaling of non-endangered stocks is deeply hypocritical.

Sustainable whaling is no less moral that commercial farming, say pro-whaling groups

Industrial meat production keeps pigs, cows and chicken in grim captivity from birth to slaughterhouse, but this seldom stops shoppers from reaching for a nice cut of pork or beef.

There is also the hunter's defence that killing a wild animal is more ethical than raising an animal in captivity with the sole purpose of eating it.

Lars Walloe, former head of Norway's delegation to the IWC, told the BBC whaling is the same as killing "other large mammals in the forest, like deer, elk, moose".

"We kill them for meat and we don't see the difference between killing a minke whale and a moose as long as it's done humanely."

What's the likely verdict?

Leading anti-whaling nations like Australia have already said they would band together to reject any attempts to undermine the current ban.

Australia has long been Japan's major opponent when it comes to whaling and wants to strengthen the IWC's protection of whales. It would face fierce opposition at home if it changed its mind.

Canberra took the issue to the International Court of Justice, which in 2014 ruled against Japan, saying it was not necessary to kill whales in order to study them.

Scientific whaling is widely seen as a poor disguise

But that was in reference to one specific scientific programme - so Japan simply changed said programme and resumed whaling.

Japanese officials, however, have told the BBC they hope the new proposal will be considered and adopted. "This issue should be resolved based on science and international law, but not with emotion," urges Hideki Moronuki.

Donald R Rothwell, professor of international law at Australia National University, told the BBC an end to the moratorium might not ultimately have much impact.

"If Japan would offer to end its scientific programme, a future commercial whaling quota would likely see very little change in the actual number of whales killed," he said.

Under the scientific programme, Japan takes around 300 to 400 animals each year and a commercial quota could limit them to a similar number.

Currently, some of the whales are hunted in a whale sanctuary in the Antarctic. Japan argues the sanctuary is to protect against commercial whaling but that scientific whaling does not break any rules.

Whales caught by Japan for research do often end up on the plate

If in future, Japan was to whale under an IWC quota for commercial purpose, it would be bound by the sanctuary rules.

And if Japan were simply to leave the IWC, it would still be bound by international laws that bind countries to "co-operate on whale conservation".

But ultimately, there's a good chance the contentious issue will gradually die down by itself.

Japanese demand for whale meat has long been on the decline.

The industry already survives on state subsidies so eventually, changing tastes might mean commercial whaling is undone by plain commercial arithmetic.

- Published20 July 2018

- Published8 August 2018

- Published2 June 2018

- Published11 July 2018

- Published7 August 2018