Japanese whaling: why the hunts go on

- Published

The mechanisation of whaling enabled countries, including many who now oppose it, to greatly increase catches

Japan's whaling ships returned from their Antarctic hunt on Thursday with 333 minke whales on board, their entire self-allocated quota.

Of the whales killed, 103 were male and 230 female, 90% of them pregnant, said Japan's fisheries agency. It said that showed the population was in a healthy breeding state.

Australia has branded the slaughter "abhorrent", its environment minister saying Japan's scientific justification for the hunt did not exist.

What are the issues behind Japan's whaling programme, and why has compromise been so difficult?

Isn't whaling banned?

Not quite. The International Whaling Commission (IWC), which regulates the industry, agreed to a moratorium on commercial whaling from the 1985. But it did allow exceptions, enough for Japan to hunt more than 20,000 whales since.

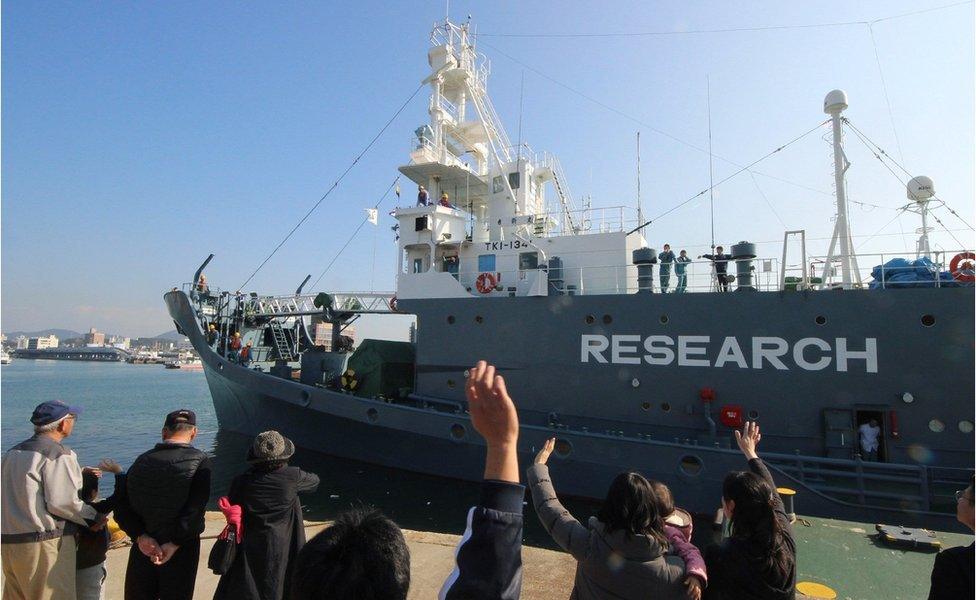

Despite the word "research" on the sides of Japan's whaling ships, many remain unconvinced

It is those exceptions to the moratorium that allow for whaling activity. They are:

Objection or reservation

Norway simply rejects the moratorium, while Iceland whales "under reservation" to it. Both still whale commercially - 594 minke were taken by Norway and 169 (mostly fin whales) by Iceland in 2013.

Aboriginal Subsistence

Practiced by indigenous groups in places like Greenland, Denmark and Alaska. The flexible definition allows for "cultural" subsistence so it does not have to be about nutritional necessity. Greenlanders sell whale meat to tourists for example and even non-indigenous groups like the Bequians in St Vincent & the Grenadines, can whale

Scientific Research

Famously used by Japan, this is the exemption that has run into problems.

Wasn't Japan's whaling ruled unscientific?

Yes and no. In 2014, the United Nations' top court, the International Court of Justice (ICJ), noting a relative lack of recent discoveries, said Japan's Antarctic whaling programme, JARPA II, was insufficiently scientific to qualify. But it did not ban research whaling.

The ICJ, based in The Netherlands, is the United Nations' top court

The Antarctic Southern Ocean hunt is the largest and most controversial of Japan's hunts.

Following the decision, Tokyo granted no Antarctic whaling licences for the 2014/15 winter season, though it did conduct a smaller version of its less well-known north-western Pacific Ocean whaling programme, which was not covered by the judgment.

It then created a new Antarctic whaling programme, NEWREP-A. Japan insists this meets the criteria set out by the ICJ for scientific whaling. It has cut the catch by around two-thirds, to 333 and covers a wider area. It also specified more scientific goals.

Since then one IWC expert panel said the new plan did not adequately demonstrate the need to kill whales to meet its research objectives. But the final IWC Scientific Committee meeting was split.

Is the research argument genuine?

Japan says it is trying to establish whether populations are stable enough for commercial whaling to resume.

But research is almost never mentioned by ordinary Japanese whaling supporters, who are more likely to cite tradition, sovereignty and the perceived hypocrisy of anti-whaling nations.

Prof Atsushi Ishii of Tohoku University, an expert in environmental politics, argues it is an excuse to subsidise an unprofitable but politically sensitive industry.

Japan's whaling negotiations, he says, "actually make the lifting of the moratorium more difficult," and deliberately so.

Without the implicit subsidy, he says, whaling companies "would go into bankruptcy very easily - they can't sell the whale meat".

Is whale meat popular in Japan?

Is Japan losing the taste for whale meat?

The scientific whaling exemption allows for by-product, in this case dead whales, to be sold commercially. That meat, blubber, and other products, is what ends up being eaten.

Critics say they contain dangerously high levels of mercury. Nevertheless it is not a popular meat in Japan.

The whaling industry has tried to reverse perceived indifference by organising food festivals and even visiting schools.

Is compromise possible?

Alternatives to the hunts have been proposed:

A much smaller, even more scientifically focused hunt. Whether such a programme would be economically sustainable is another question.

"Small-type coastal whaling", similar to Greenland's. Smaller, while still appeasing those who say whaling is a cultural right. But this is rejected by opponents as a front for commercial whaling.

The 2010 "peace plan", proposed by the IWC's then chairman, would have lifted the moratorium for 10 years in exchange for sharply lower quotas and other restrictions. But anti-whalers could not stomach accepting any commercial whaling and Japan thought the cuts were too great.

A "whale conservation market". US researchers in 2012 borrowed an idea from pollution markets and suggested countries be allocated tradable whaling quotas, based on an agreed sustainable total.

Return to commercial whaling. With no government subsidy, catches would have to drop significantly. Hunts far from Japan's shores would likely end entirely.

There is one potential game-changer; Prof Ishii points out that Japan's only factory whaling ship, the Nisshin Maru, will need to be replaced before long "at huge cost". This may be a cost the government is reluctant to bear. Without it, some whaling could persist, but big hunts far from Japan's shores would be impossible.

Reporting by Simeon Paterson

- Published1 December 2015

- Published15 February 2016

- Published8 February 2016