Indonesia tsunami: Palu hit by 'worst case scenario'

- Published

Indonesia experiences earthquakes every day, but the scale of the quake and tsunami which hit Palu on Friday took local people and scientists by surprise.

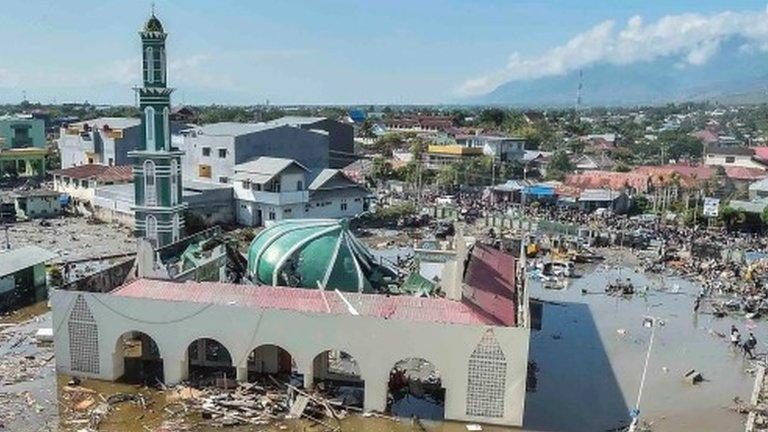

More than 1,000 people have died, but the final figure could be much higher, say officials.

As scientists explained to the BBC, a combination of geography, timing and inadequate warnings meant that what happened in Palu was a worst case scenario.

A perilous location

Earthquakes are caused by the Earth's tectonic plates sliding against or under each other. This is happening constantly, but sometimes the movement is big enough and close enough to populated areas to have devastating consequences.

Small tremors had been happening throughout Friday in Palu, but in the early evening the Palu-Koru fault suddenly slipped, a short distance off shore and only 10km (6 miles) below the surface, generating a 7.5 magnitude quake.

Hamza Latief, from the Bandung Institute of Technology, has been studying the fault line since 1995 and says the impact of the quake was magnified by the thick layers of sediment on which the city sits.

Buildings sitting on thick sediment, like here in Palu, will more easily be brought down than those on rock

Whereas rock just shakes in a quake, sediment moves around a lot more, essentially behaving like liquid. Few poorly built properties can withstand such movement.

"Any place where people have put buildings on fill - where they've dug dirt and moved it to another place - is not going to be as solid as bedrock," says Jess Phoenix, a US-based geologist who has studied Indonesia.

When it comes to quakes, she says, "those are the areas to worry about".

An unexpected wave

"You don't normally pay much attention to the Palu-Koru fault line, as far as tsunamis are concerned," says Prof Philip Liu Li-Fan at the National University of Singapore.

Tsunami survivor: "I was hugging my wife, but when the wave came... I immediately lost her"

That's because the two plates are moving horizontally, not with the vertical thrust usually required to set off dangerous waves.

"We have been trying to figure out what was really going on," says Prof Liu.

It could be that the quake kicked off a landslide underwater, which in turn disturbed the water, he says, or there could be inaccuracies in describing the fault, but "we don't really know yet".

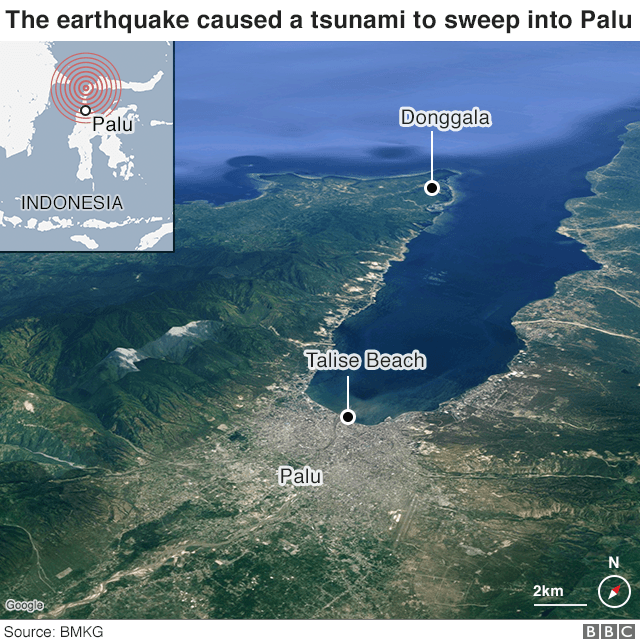

But once the wave started moving, Palu - at the end of a narrow 10km-long bay, was a sitting duck.

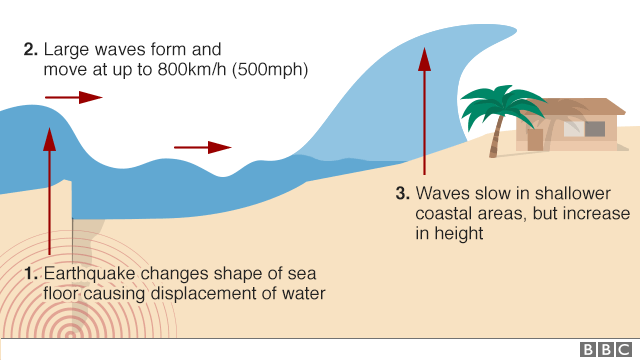

Tsunamis are no danger when out at sea. But when the waves come closer to land, their base drags on the seabed causing them to rise up.

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

Within three minutes, Palu was hit by three waves.

Jess Phoenix said the geography and timing meant it was "basically a worst case scenario".

"When water comes into a horseshoe-shaped area like that, instead of the wave increasing just because the ocean is getting shallow, you also have the bowl effect, where the waves are going to reflect off the shoreline around it."

Mr Latief says the area has been hit by tsunamis before. Historical records show that in 1927, one wave was 3-4m at the mouth of the bay but had risen to 8m by the time it reached the town.

An ineffective warning system?

After the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami killed a quarter of a million people, huge amounts of money were spent on an early warning system.

A complex system of sensors were installed across the region. These are meant to help scientists quickly assess whether a quake is likely to trigger a tsunami, and alert the public to move to higher ground.

A system of buoys were donated to Indonesia to send alerts about tsunami threats - but none are currently functioning

The head of Indonesia's disaster mitigation agency has said that a key part of the country's warning system - a series of buoys connected to seafloor sensors designed to detect tsunamis - had not been working since 2012. He blamed a lack of funding.

Prof Liu says the system is "sort of working and sort of not working", and that Indonesia's focus has largely been its southern regions, which were so badly hit in 2004.

A tsunami warning was issued after the quake, but, says Jess Phoenix, "it'll be interesting to see what comes out about whether the warning was implemented correctly, whether people heard it".

Many countries hit by the 2004 tsunami, like Sri Lanka, have since installed signs showing the route to higher ground

It's not unusual for people to be killed by a tsunami because they stayed to look at the spectacle of the sea suddenly drawing back as the wave builds up. Since 2004, a huge amount of effort has gone into educating people to run inland if the water retreats.

One man told the BBC's Rebecca Henschke he saw the sea disappear and sent his family running to higher ground while he grabbed a nearby child and clung to a tree.

But despite the warning, it appears there were still lots of people on or near the beach in Palu, many of them setting up for a festival.

"People in that region are really familiar with what tsunami can do. I'm hopeful that if there were casualties on the beach they were trying to leave," said Ms Phoenix.

"But a 10ft wave is really substantial. To get everyone evacuated in a very short amount of time you have to have very clear egress routes marked.

"From my experience working in Indonesia, I didn't see super clearly marked egress routes. I'm not sure about that particular town, but it is really hard to get a large amount of people out of an area quickly."

- Published30 September 2018

- Published30 September 2018

- Published2 October 2018

- Published29 September 2018

- Published1 October 2018

- Published1 October 2018