How New Zealand is trying to take on child poverty

- Published

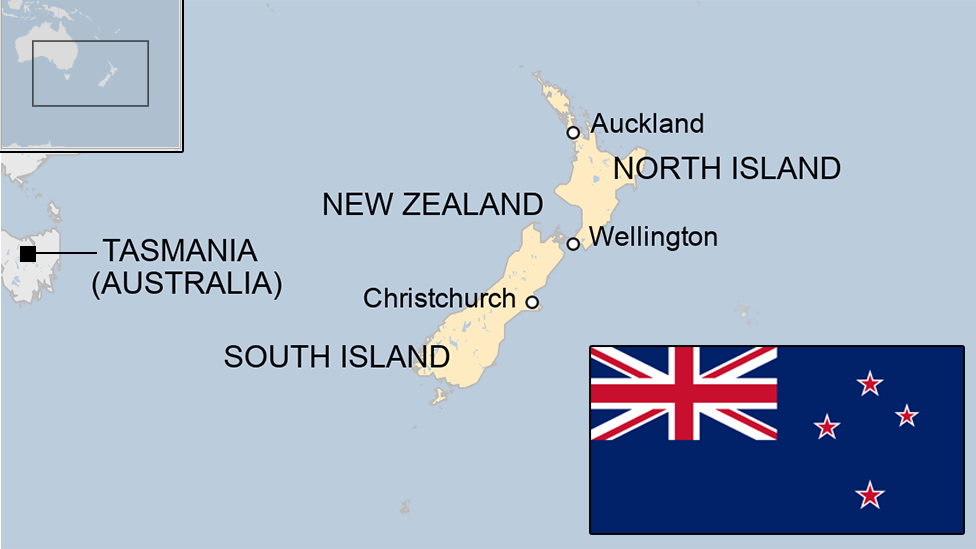

It's home to glaciers, national parks and vineyards, but there's also a darker side to New Zealand

It's a mountainous wonderland decorated with ancient glaciers, breathtaking national parks and sumptuous vineyards, but behind its glossy image New Zealand is failing many of its children.

Rates of disadvantage have stayed stubbornly high and they are a stain that Jacinda Ardern, who became New Zealand's youngest female prime minister a year ago, is determined to cleanse.

She has promised to halve child poverty over the next 10 years, insisting that her South Pacific nation should "aspire to be the best place in the world to be a child".

It's a monumental task, but advocacy groups have been encouraged by what they've seen in the first year of the Ardern administration - a left-leaning, three-party coalition.

"It is a bit of a shock and revelation to all of us as New Zealanders to realise that that are about 280,000 children who live in low-income families or families that experience material hardship, and that's about 27% of all our children," explained Vivien Maidaborn, executive director of Unicef New Zealand.

Some 280,000 children in New Zealand are from low-income families

"With the change in government we suddenly stopped arguing that this was a problem. The [previous] National government couldn't even agree the definition of poverty let alone what they were going to do about it," she told the BBC.

"We worked hard to make this the election issue of our time and we succeeded. We have a prime minister saying it is her number one priority and that means the policy levers are suddenly in action."

'I'm always terrified'

Among the measures have been cash and housing assistance to low-income families, a winter energy payment and new benefits for newborns. For many, the changes have already filtered through.

"Within the first six months my income went up. I make ends meet but it is only just. I'm always terrified about what if something happens and I'm laid off for a month or so," said Jodie, a 36-year old single mother, who works full time for a hire car company and voted for Ms Ardern's Labour party at the last election.

"Given the promises they made they are actually doing really well, especially given she squashed in birth in the middle as well. That is fantastic."

Jodie and her three children live in temporary accommodation provided by the Salvation Army in Nelson, a South Island city of 50,000 people, where affordable housing for those on low incomes - like in other parts of the country - is in short supply. She recently moved from a caravan park following a relationship breakdown.

A caravan park in New Zealand

"That was a pretty hard time. The children are quite resilient [and] they are all adaptable. However, it does affect them. My daughter and my middle son just don't do too well with instability and were lashing out in their own ways," she told the BBC.

"I don't hide how harsh the world can be from them. I need to show them how to deal with it."

A year ago the glow of Jacinda-mania spread far beyond the shores of New Zealand. She became a global sensation.

Within seven weeks of a surprise elevation to leader of the opposition, she was fighting an election campaign in September 2017.

More surprises would come as she adeptly negotiated New Zealand's system of proportional representation and post-poll horse-trading to forge a governing alliance comprising the Greens and New Zealand First, led by the veteran populist, Winston Peters.

Jacinda Ardern became a global sensation when she was made prime minister

Although the anecdotal signs on the core mission to cut child poverty appear positive, New Zealanders are yet to find out how much has really changed, according to Associate Professor Grant Duncan, a political commentator from Massey University.

"At the moment we can't give them credit for any results because we're still waiting for statistics. At this stage I wouldn't say that the government has really made a dent in child poverty because we've got no evidence," he said.

However, new measures will bring one of the most corrosive social issues right into the engine room of government.

"The finance minister will be required by law to account for the impact the budget is expected to have on child poverty reduction and how they have been doing so far," added Prof Duncan.

The best chance for children?

There is no universally agreed measurement of poverty, although a common benchmark is household income that's between 50-60% below the national average.

A new Child Poverty Reduction Bill should provide greater clarity about how to gauge disadvantage and levels of hardship.

Susan St John, a spokeswoman on economics for the Child Poverty Action Group, told the BBC she is excited by the prime minister's zeal, but is concerned at the rate of progress.

A common benchmark of poverty is household income that's between 50-60% below the national average

"We were hopeful they would do more early on in their first term, but there is the danger of them going into an election year with a raft of policies that might be politically unpopular in many quarters. We're a little bit anxious about how it will unfold."

However, she adds that Ms Ardern is "the best thing that has happened for poor children in New Zealand for a very, very long time."

"We are very encouraged, we are expecting great things, she is in a coalition government and that makes it more difficult but this is the best chance that children have had for a long time," she said.

- Published23 March 2018

- Published2 April 2018

- Published17 September 2018

- Published22 August 2023