The mega-dam being crowdfunded by Pakistan's top judge

- Published

The proposed site of the Diamer-Bhasha dam in Gilgit-Baltistan

Cash-poor Pakistan is crowdfunding a drive to collect almost $17bn from its citizens, officials, businesses and stars in order to build two massive dams to help counter a future water crisis.

One of the dams would be among the biggest in the world. But is the project for real or is it a monumental folly, as some are calling it?

If it's ever built, the dam at Diamer-Bhasha in the north-west would have a generating capacity of 4,500MW and stand 272m (892ft) high, making it the world's sixth tallest dam.

Located near the Himalayan peak Nanga Parbat, it would block off a huge valley system on the upper reaches of the Indus river.

The dam has been talked about for more than a decade, but plans to begin construction were given fresh impetus this summer not by water experts or ministers - but by Pakistan's top judge, Chief Justice Saqib Nisar.

Following a report predicting severe water shortages in the country by 2025, he set up a fund to raise $14bn to build the mega-dam in Diamerg, and $2.5bn to build an 800MW dam in Mohmand, about 120km (75 miles) to the south-west.

"It is possible that we will get more money than the required amount," said the judge.

Justice Nisar became the first donor, contributing roughly $8,000 to the fund. Many others have since followed suit.

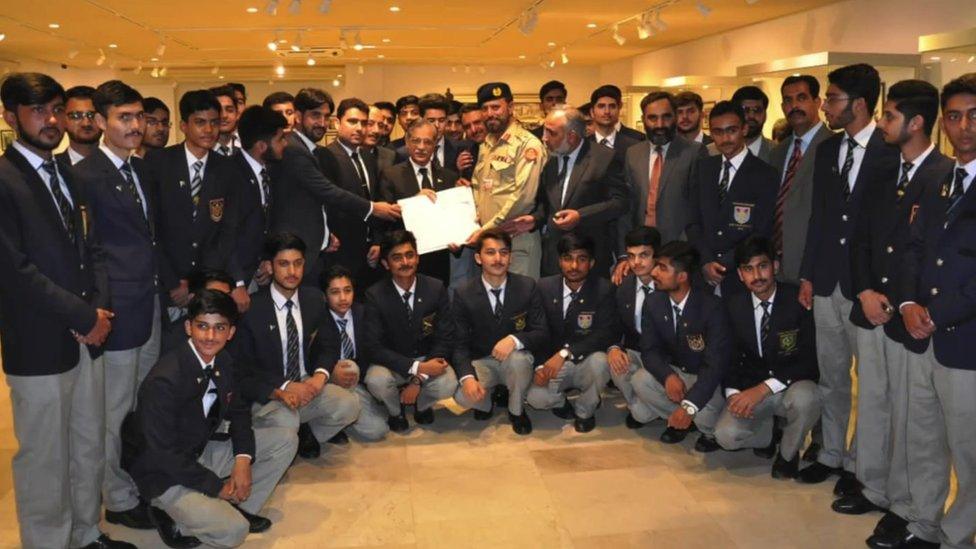

These include various branches of the military, which have donated a whopping $7.3m. Businesses, officials, sports stars, school pupils and other ordinary people are among those who have also stumped up cash.

Pakistan's army chief is among those who have donated to the chief justice's dam fund

Even schoolchildren have contributed to the fund

Almost every day there's a press release from the Supreme Court with news of different individuals and institutions meeting the chief justice and donating to the fund. Many have cases pending in court, which has raised suspicions they may be trying to influence the judiciary.

There are many donors who appear glad to have contributed, but not all agree.

Marium Zia Khan, an Islamabad resident, told the BBC she would not contribute to the fund.

"While I understand water scarcity merits urgent attention... crowdfunding mega infrastructure projects such as a dam is a flawed idea."

Critics have been warned they may be tried for treason if they make fun of the fund.

But the pro-dam lobby is free to express its opinion - and there's an air of hysteria about the urgency to build more dams, with telethons and advertisements urging people to contribute as their patriotic duty.

Last month Prime Minister Imran Khan joined in, external, delivering a special address in which he asked overseas Pakistanis to contribute $1,000 each to the dam fund. He also presided over a fundraising dinner in Karachi in September, where he managed to raise almost $6m.

"I am the greatest fundraiser in the history of Pakistan," he said afterwards.

"I assure you that we have to meet our target of 30bn rupees every year and we will meet more than our target as all Pakistanis have been mobilised today."

But the reality has been rather different so far. Five months after the fund was established, contributions add up to just over $50m - a trickle compared with the vast sums it is estimated the two dams would cost.

This at a time when Pakistan is seeking loans from the IMF and other countries to stave off a balance of payments crisis and to service its debt.

What are people saying about the dam?

Danish Mustafa from King's College department of geography is not optimistic the dam will be built.

"I can't imagine this drive working. No country in the world has ever undertaken an infrastructure project which is almost 10% of its total GDP. You have to be semi-insane to want to do that," he said.

In 2014, researchers at Oxford University published a study on 245 large dams built around the world from 1934-2007, and found mega-dams "don't make economic sense".

They singled out the Diamer-Bhasha Dam project as a case study for potential cost and construction overruns.

If construction had started in 2010, the findings suggested, it wouldn't have been completed until 2027 - by which time the total cost could have ballooned to close to $30bn.

The designated site of the Diamer-Bhasha dam

One of the authors of the report, Prof Bent Flyvbjerg, compared those seeking to build mega-dams to "fools and reckless optimists".

He told The Ecologist journal in 2014 that such projects also ran the risk of the public being misled "for private gain, fiscal or political, by painting overly positive prospects of an investment".

Villages such as this one would be submerged if the dam were built

Shams-ul-Mulk, former chairman of Pakistan's Water and Power Development Authority (Wapda), firmly disagrees.

"Pakistan will face a drought-like situation if large dams are not constructed," he told the BBC.

"Those who oppose the construction of large dams are not aware of the looming water crisis in the country and don't want Pakistan to progress."

Does Pakistan have a water shortage?

But this raises questions over whether Pakistan is actually a water-scarce country.

A 2015 IMF report put total annual availability of water at 191 million acre feet (MAF), which it said would become insufficient by 2025 when demand is expected to rise to 274 MAF.

Pakistan's leaders say new dams are desperately needed

Many say this is due to Pakistan's surge in population which has already tripled since 1970.

But experts point out that little or nothing has been done to ensure water is used more efficiently.

Hassan Abbas, a hydrology expert, says the solution for periodic shortages "does not lie in another mega structure. It lies in improving our management practices."

This would require efficient irrigation - such as drip irrigation and paving of water-courses to reduce seepage - as well as steps to reduce water loss.

Then there are the socio-economic and ecological costs of constructing mega structures on water courses, often with serious political implications.

After signing a water treaty with India in 1960, Pakistan built two of the largest dams in the world, Tarbela and Mangla. The purpose was both to generate electricity and divert water for irrigation.

While it improved the electricity situation in the country for some time, it gradually led to the desertification of millions of acres of land in the Indus Delta, external region of Sindh province.

Upriver, hundreds of villages were submerged and thousands were uprooted by the building of reservoirs. Compensation was promised and rehabilitation plans made, but locals are still waiting for a full and final settlement.

Tarbela dam was built in the 1960s, but such projects have been controversial

Meanwhile, mudflows carried by the rivers created silt deposits at the dams, depleting their storage capacity.

Other controversial dam projects have since been shelved, but many have gone ahead.

Is there another way?

None are on the scale of Diamer-Bhasha, which was floated as an idea in the early 2000s.

But global financial institutes such as the World Bank have consistently refused to provide funding, citing the seismicity of the area and saying the dam would be controversial, since India claims ownership of Gilgit-Baltistan, its proposed location.

Backers of the mega-dam argue it is not designed to divert water for irrigation and therefore there would have no negative impact on agriculture in Sindh.

But experts believe it will still hurt the Indus Delta region, where residents are already protesting against the building of the dam.

So why has Pakistan's top judge gone out of his way to promote this?

The answer may lie in the huge appetite for irrigation water in Punjab, politically the country's most influential province and home to just under 60% of its population.

Pakistan has the world's largest canal irrigation system - and most of it ends up in Punjab, to the annoyance of other provinces.

Or could it be there's an element of national pride that was piqued when international funding for the project was withheld.

Access roads have already been supplied to the Diamer dam site

Either way, there are other ways of raising the huge sums of money required for dams.

Simi Kamal, a geographer, says there is room for dams in Pakistan - but suggests water bonds as a "more rational" way of fundraising than charity donations.

As an example she points to the $5bn Great Ethiopian Renaissance Dam, which was funded in large part by this method.

"We should not be making speeches for or against dams, or make dams into idols or ideology," she told the BBC.

"It is not that simple. The current clamour for dams and frenzied soundbites by (mostly) ill-informed people is quite immature and requires restraint until we have good science and a better knowledge base in place."

- Published22 December 2016

- Published11 March 2014

- Published26 July 2018

- Published15 March 2024