Karachi Press Club: Shock as authorities raid ‘island of freedom’

- Published

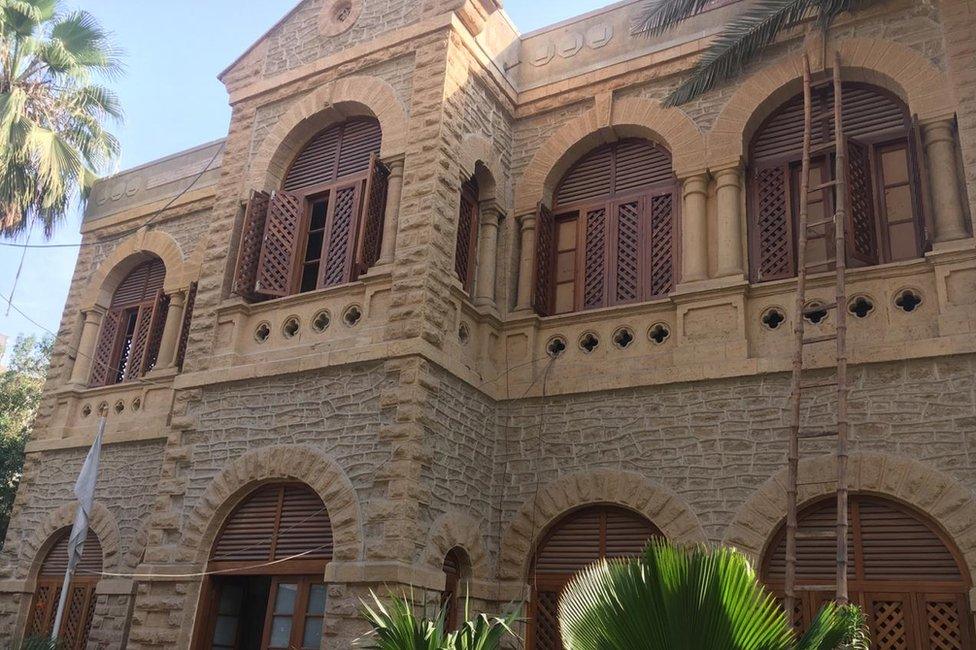

Pioneering journalists acquired a mansion and founded the Karachi Press Club in 1958

Through decades of military coups, civil unrest and martial law, the Karachi Press Club has remained off-limits to Pakistan's powerful military and intelligence agencies.

But this island of democratic resistance in a country prone to religious bigotry and militarisation has finally been violated.

Late at night on 8 November, more than a dozen plainclothes men carrying guns forced their way into the club - examining rooms and shooting videos and photos of the premises.

The group, who arrived at the club in half a dozen trucks led by a police van, quickly left when confronted by members. Police later said they were tracking signals from the mobile phone of a wanted man they thought was in the building.

The next day, security agencies arrested a senior journalist at his home on charges of keeping Islamic State group material.

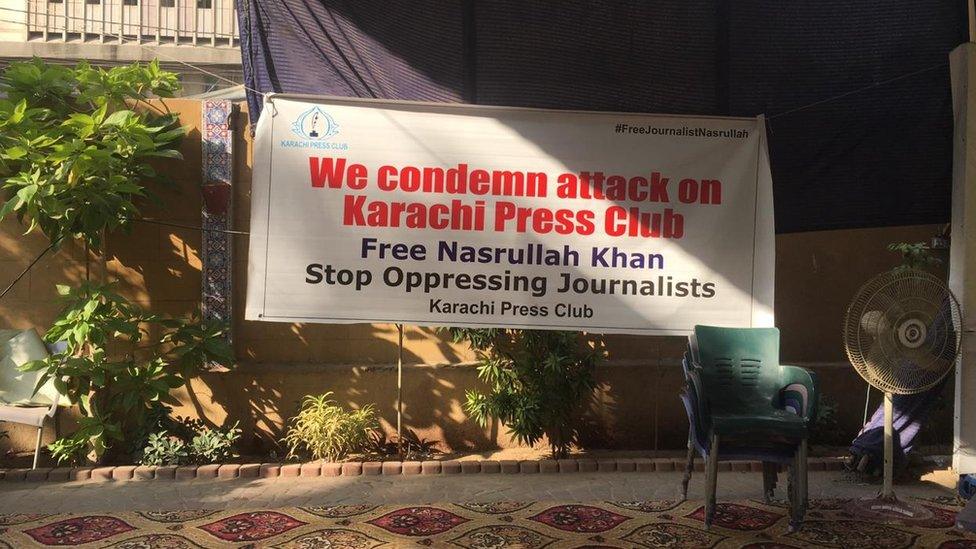

The club responded by saying the arrest was made to justify the raid and defuse protests by journalists, which have been held in all Pakistan's major cities.

But while the mainstream media has largely avoided turning it into a major controversy, the country's reporters and editors remain in shock.

Never in the club's 60-year existence has a security agent been allowed to so much as take a stroll on its premises. It is an inviolable rule of the club.

Under club rules, uniformed personnel and intelligence officials are forbidden to enter

In December 1958, a small group of pioneering journalists got together to acquire an impressive mansion built by a Parsi family in 1883, and there they set up the country's first press club.

Those pioneers, like most journalists of their time, were political activists linked to the progressive left-wing, and had a strong trade union.

The club was inaugurated just months after the country's first military takeover, and served as an early base for journalists to test their muscle against a regime that was soon to set up a National Press Trust (NPT) to control the media. A number of newspapers were later taken over by the NPT and used to propagate policies of the regime.

Many of the Karachi Press Club's rules were set up in this environment, and the club's strict adherence to those rules over decades has given it an iconic status among journalists around the country.

One such rule relates to annual elections. Even in the worst of circumstances, the KPC has never failed to elect a new governing body every single year since 1958.

Another is a complete ban on the entry of uniformed personnel and intelligence officials.

Mujahid Barelvi, a veteran journalist based in Karachi, recalls an incident in the 1970s during the third military regime - that of General Zia-ul Haq - when a senior military official, Siddique Salik, walked into the club to have a cup of tea. He was forced to leave.

Known for his famous book, Witness to Surrender, which describes events that led to Pakistan's defeat in the 1971 Bangladesh war, Mr Salik was looking after the Zia regime's public relations at the time.

Mr Barelvi remembers that as the official left the KPC, he was taunted by a Dawn newspaper journalist and later club president, the late Sabihuddin Ghausi. "You should write another 'Witness to Surrender' now," he quipped.

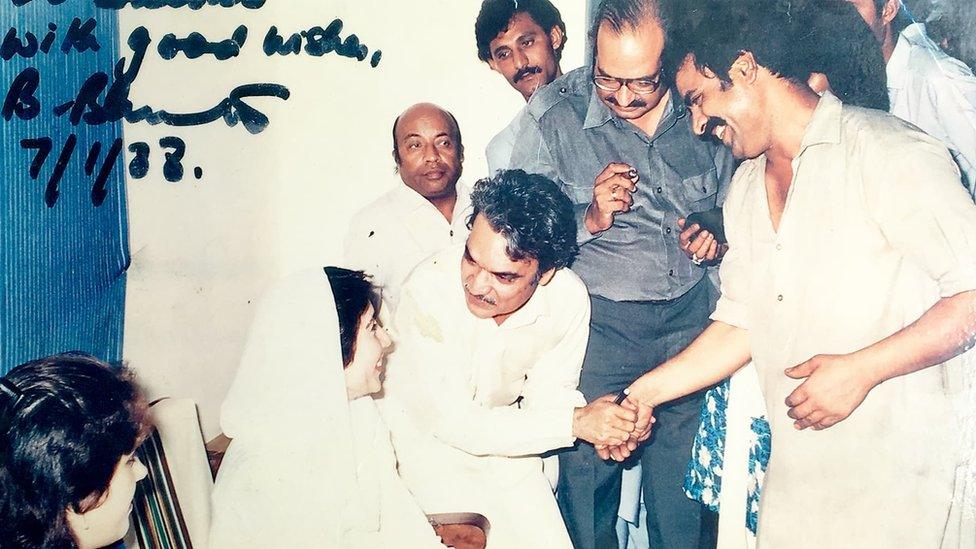

Benazir Bhutto, who would later become prime minister, greets a popular waiter, Sattar, at the club in 1988

Some other KPC rules which have endured to this day are rooted in the secular, urban culture of 1950s Karachi. This culture was mainly a product of the mixing of the city's older Catholic and Parsi populations with educated Muslim urbanites from northern India, who moved to the city in droves after the partition of India in 1947.

Together these groups supplied Karachi's - and for the most part Pakistan's - first generation of journalists. Most of them were involved with left-leaning political groups and were fiercely opposed to the mixing of religion with politics.

One of those rules was - and still is - that the club's dining hall never closes during the Muslim fasting month of Ramadan, even though eating in public places during the month is a criminal offence. More surprisingly, the KPC remains the only place in today's Pakistan that has a formal bar where alcoholic drinks are served.

More from Ilyas on Pakistan

When the Zia regime embarked on its programme to Islamicise Pakistan in the late 1970s, it banned bars and discotheques - which had survived in Karachi until then - and also introduced the Ramadan ban on eating in public places.

The KPC was an obvious target.

Mr Barelvi, who was the club's secretary-general in 1978, recalls the day before the advent of Ramadan, when the club received orders to close the dining hall and the bar.

"We let them know that it was not going to happen, and that they will have to walk over us to enter the club," he said. "Next morning we gathered outside the KPC gate and waited. But they had sensed our mood and nobody came."

Gen Zia banned political activity all over the country, but the club was one place where his writ did not run. It continued to offer its premises for resistance leaders to hold their meetings.

This prompted the regime's information secretary, General Mujibur Rahman, to famously describe KPC as "enemy territory." In an equally famous retort to the general, one of the most celebrated Urdu poets of the post-1947 era, Faiz Ahmed Faiz, said it was "the only liberated territory".

But much water has flowed under the bridge since then.

The policy of Islamicisation, and the subsequent spread of militancy, has not only divided the nation, but also divided and weakened journalists' unions.

In the meantime, many believe the growth of the military's business and industrial empire since the 1970s has strengthened its desire to keep control over political decision-making.

The club has clung to secular traditions over decades

These developments have come at a time when major business houses have started their own media wings. The owners are replacing professional editors, and framing policies aimed more at profit-making than robust and probing journalism.

These media outlets have easily complied with the security establishment's need to curb objective reporting across large parts of the country, where the military is accused of indulging in gross human rights violations.

The government is now planning to introduce a new regulator - the Pakistan Media Regulatory Authority - to ensure centralised control of the media.

The purpose, as one official told me, "is to ensure more backing and support for the national security institutions which has been lacking so far, unlike the rest of the world where the media is free to criticise the government but it protects state policies".

Few veteran journalists agree with this contention. They fear that the state is trying to set up a "China model" of media management, where the interests of the ruling circles take precedence over wider public interest.

One journalist suggested the raid on the Karachi Press Club may have been an attempt to provide a release valve for whatever resistance remains among journalists - so their protests run out of steam before the intended legislation is tabled.

While many tend to agree, some are hopeful that the journalistic fraternity still has some fight left in it.

Salim Asmi, a retired journalist in his seventies and the former editor of Pakistan's prestigious Dawn newspaper, is one of them.

"Let's see who runs out of steam first, us or them," he said.

M Ilyas Khan is a former member of the Karachi Press Club and is currently a member of the Islamabad Press Club.

- Published17 December 2017