'My parents were told to swap me for a boy'

- Published

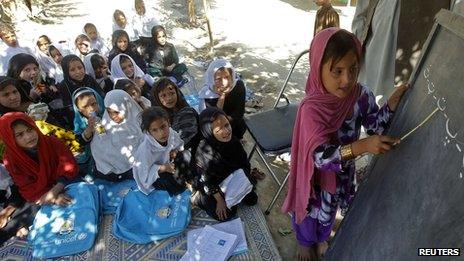

Nargis now campaigns for women's education in her home country

When Nargis Taraki became the fifth girl born to her parents in Afghanistan, her parents were told they should swap her with another baby in the village.

Now 21, she has made it her life ambition to prove they were right to keep her.

Nargis now campaigns for women's education and empowerment in her home country, and is one of the BBC's 2018 100 Women.

In 1997 I opened my eyes to the world as my parents' fifth child, and their fifth girl.

My father's sister, and other relatives, immediately put pressure on my mum to agree to my father taking a second wife. Taking a second or even third wife is not uncommon in Afghanistan, and is sometimes done because they believe a new wife could mean a new chance to have a male child.

When she refused, they suggested that my father swap me for a boy. They even found a family in the village who was willing to give their boy away and take me.

Swapping children is not something that is part of our culture, and I haven't heard of it happening before, but boys are more valued in Afghan society as the traditional family breadwinners.

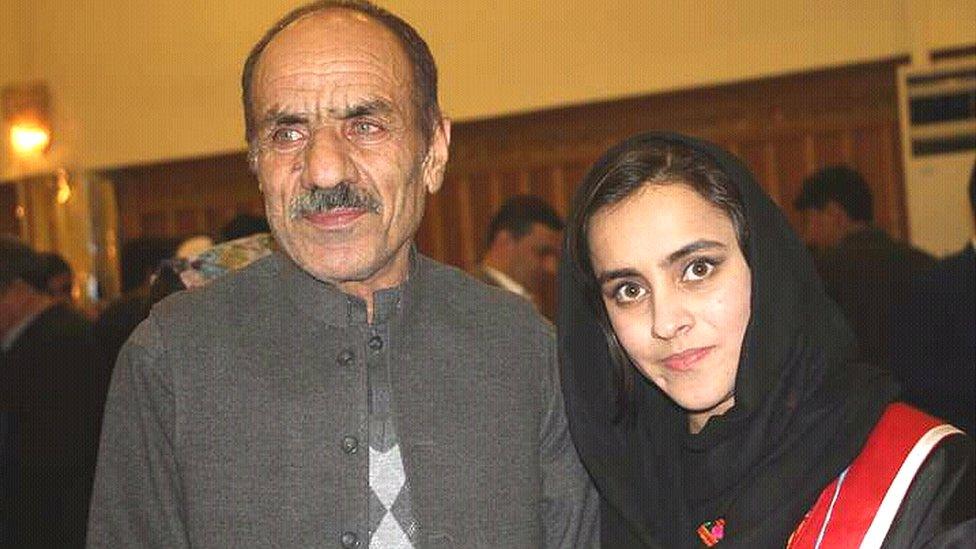

Nargis credits her father's support for her ability to get an education

People deliberately said things to upset my mother and make her feel inferior for not having a son. Despite her refusal to part ways with me, some elders still kept approaching my father. But he had a completely different mentality. He told them he loved me, and he would one day prove to them that a daughter can achieve everything a son can.

It was not an easy time for my father. He had a military background and a history of service in the previous Soviet-backed regime, and my native district at the time was controlled by people with religious or fundamentalist tendencies.

So certain people in the village used to detest him and did not socialise with us.

But my father believed in what he said, and he always stood by his word. Although there was pressure on my parents to swap me because I was a girl, it was a man who had the most positive impact on my character.

Fleeing home

Things got worse for us after Taliban militants took control of our district. In 1998 my father had to flee to Pakistan and soon after that we joined him there.

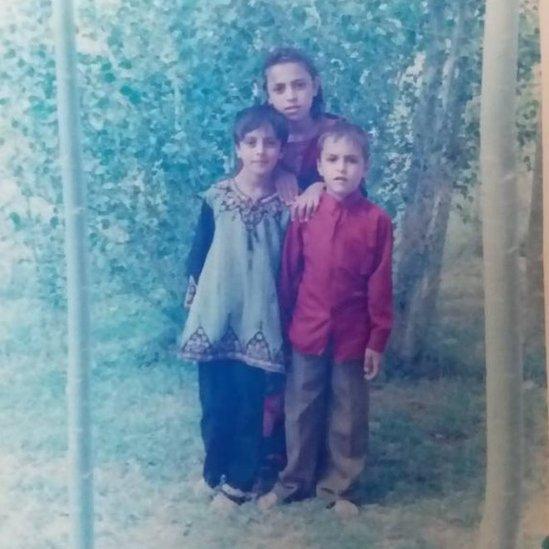

Life there was not easy - but he managed to get work as a manager in a shoe factory. Perhaps the best thing to happen to my parents whilst in Pakistan was that they finally had a son, followed by my fifth sister.

Nargis (left) with one of her sisters and younger brother

In 2001, we all returned to Kabul after the Taliban regime was toppled. We didn't have a house of our own and had to live with my uncles. My sisters and I managed to keep going to school despite conservatism in our culture.

I went on to study public policy and administration at Kabul University and graduated two years ago with the highest marks for that year. Throughout that time my father never stopped supporting me.

A couple of years ago I went to watch a cricket game in Kabul with my sister. There weren't many women in the stadium and our photographs and videos were circulated on social media. People started criticising us and leaving negative comments, saying we were shameless to be in a stadium amongst men. Others said we were trying to spread adultery and were being paid by the Americans.

When my father saw some of the comments on Facebook, he looked at me and said: "My dear. You have done the right thing. I am glad you have annoyed some of these idiots. Life is short. Enjoy it as much as you can."

My father died of cancer earlier this year. In him, I lost someone whose constant support made me into the person that I am today, and I know he will always be with me.

Nargis presenting a talk at a Forward Together Afghanistan event

Three years ago I tried to open a school for girls in my native village in Ghazni. I talked to my father about it and he said it would be almost impossible because of cultural boundaries, and even boys have difficulties because of the security situation. My father thought giving it a name of a religious madrassa might have improved our chances.

In the end I was unable to travel to my native village because it was simply too dangerous. One of my sisters and I still hope to achieve this goal one day.

In the meantime, I volunteered for several years for NGOs in that part of the world, working for women's education, health and empowerment.

I've also presented talks on a girl's right to go to school, university and to get a job.

I've always dreamed of studying at the University of Oxford one day. When I look at international university rankings I always find Oxford in first or second position, and when I compare that with Kabul University I feel a bit sad - although that's not to say I'm not thankful I was able to go.

Nargis has given talks on the importance of education

I love to read in my spare time - an average of two to three books a week - and Paolo Coelho is my favourite author.

'No compromise'

In terms of marriage, I would like to choose someone myself and my family have given me permission to marry someone of my own choice.

It would be great if I can find someone who has the same qualities as my father. I would want to spend the rest of my life with someone who has a similar attitude - who can support me and stand by my choices.

Family is also important - sometimes you marry the best man out there but then you cannot adapt to his family.

They will have to support me in what I want to do in my life. If they resist then I will try and change their minds. I believe in what I want to achieve in life and will not compromise.

What is 100 Women?

BBC 100 Women names 100 influential and inspirational women around the world every year and shares their stories.

It's been a momentous year for women's rights around the globe, so in 2018 BBC 100 Women is reflecting the trailblazing women who are using passion, indignation and anger to spark real change in the world around them.

Read more:

- Published25 May 2018

- Published11 October 2017

- Attribution

- Published23 February 2018

- Published10 March

- Published11 October 2012