The North Korean women who had to escape twice

- Published

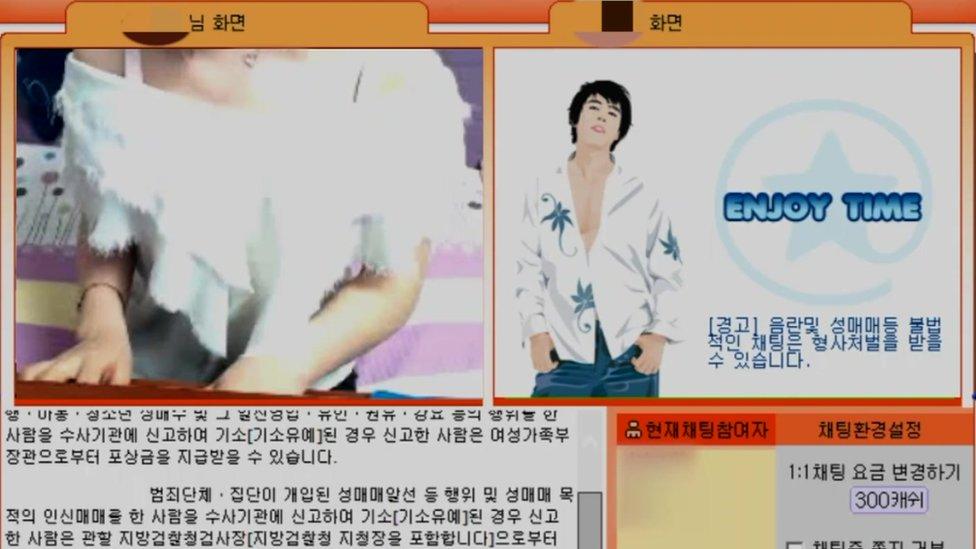

Screenshot of Jiyun on the sexcam site

Trafficked into the sex industry after defecting from North Korea, two young women spent years in captivity before finally getting the chance to escape.

From the third floor of a residential tower block in the Chinese city of Yanji, two young women hurl their torn up, knotted bedsheets out of a window.

When they pull the sheets back up, a proper rope has been tied on.

They climb out of the window and begin their descent.

"Quick, we don't have much time," urges their rescuer.

Safely on the ground, they turn and run to a waiting people carrier.

But they are not yet out of danger.

Screenshot of Mira on the sexcam site

Mira and Jiyun are both North Korean defectors and, years apart, both were tricked by traffickers.

After crossing the border into China, the same people who helped them to escape North Korea, known as "brokers" in the smuggling trade, handed them over to a sexcam operation.

Mira for the past five years, and Jiyun for the past eight, were confined to an apartment and made to work as "sexcam girls", performing often pornographic acts in front of a live webcam.

Screenshot of sexcam site

Leaving North Korea without the regime's permission is illegal. And yet many risk their lives to escape.

There is safe refuge in South Korea but the strip of land between North and South Korea is heavily militarised and filled with mines - it's nearly impossible to defect directly.

Instead, many defectors have to turn north and cross into China.

But in China, North Korean defectors are considered "illegal immigrants" and are sent back if caught by the authorities. Once back in their homeland, defectors are subject to torture and imprisonment for their "treason against the Fatherland".

Many defectors fled during the mid 1990s when a severe famine known as The Arduous March caused the death of at least one million people.

But since Kim Jong-un came to power in North Korea in 2011, the total number of people defecting each year has fallen by more than half, external. This decline has been attributed to tighter controls at the border and brokers increasing their price.

Mira defected when she was just 22.

Born close to the end of the famine, Mira grew up in a new generation of North Koreans. Thanks to a growing network of underground markets, known locally as Jangmadang, they could access DVD players, cosmetics, fake designer clothes, as well as USB sticks loaded with illegal foreign movies.

This influx of materials from outside helped persuade some to defect. The films smuggled in from China gave a glimpse of the outside world, and a motivation for leaving North Korea.

Mira was one of those affected.

"I was really into Chinese movies and thought all men from China were like that. I wanted to marry a Chinese man and I looked into leaving North Korea for several years."

Her father, a former soldier and party member, was very strict and ran the household to a tight schedule. He would even occasionally beat her.

Mira wanted to train as a doctor, but this was also stopped by her father. She became more and more frustrated and dreamt of a new life in China.

"My father was a party member and it was suffocating. He wouldn't let me watch foreign movies, I had to wake up and sleep at exact times. I didn't have my own life."

Fences run along the Tumen river

For years Mira tried to find a broker to help her cross the Tumen River and escape over the tightly controlled border. But her family's close ties to the government made many smugglers nervous that she would report them to the authorities.

Finally after four years of trying, she found someone to help her.

Like many defectors, Mira didn't have enough money to pay the broker directly. So instead she agreed to be "sold" and work off her debt. Mira thought she would be working in a restaurant.

But she had been tricked. Mira had been targeted by a smuggling ring who recruit female North Korean defectors into the sex industry.

After crossing the Tumen River into China, Mira was taken directly to the city of Yanji where she was handed over to a Korean-Chinese man she would come to know as "the director".

Mira (C) and Jiyun (R) travelled to a nearby safe house

The city of Yanji lies at the heart of the Yanbian region. With a large population of ethnic Koreans, it has become a busy hub for trade with North Korea, as well as one of the main Chinese cities where North Korean defectors live in hiding.

Women make up a large majority of defectors. But with no legal status in China, they are particularly vulnerable to being exploited. Some are sold as brides, often in rural areas, some are forced into prostitution or, like Mira, into sexcam work.

Arriving at the apartment, the director finally revealed to Mira what her new job would entail.

He paired up his new recruit with a "mentor" who would share her room. Mira was to watch, learn and practise.

"I couldn't believe it. It was so humiliating as a woman, taking off your clothes like that in front of people. When I burst into tears, they asked if I was crying because I missed home."

Mira (L) on the South Korean sexcam site

The sexcam site, and most of its users, were South Korean. They would pay by the minute, so the women were encouraged to hold the men's attention for as long as possible.

Any time Mira wavered or showed fear, the director would threaten her with being sent back to North Korea.

"All my family members work in the government, and I would be bringing shame to the family name if I returned. I'd rather vanish like smoke and die."

There were up to nine women in the apartment at any one time. When Mira's first roommate escaped with another girl, Mira was put together with another group of girls. This is how Mira met Jiyun.

Jiyun

Jiyun was just 16 when she defected in 2010.

Her parents divorced when she was two, and her family fell into poverty. She stopped going to school at 11 so she could work, and finally decided to go to China for a year to bring money back home.

But like Mira, she was also tricked by her broker and not told she would be doing sexcam work.

When she arrived in Yanji, the director tried to send her back to North Korea. He said she was "too dark and ugly".

Despite the situation, Jiyun did not want to go back.

"It's a kind of work that I despise the most, but I risked my life in order to come to China so I couldn't go back empty-handed.

"My dream was to feed my grandparents some rice before they leave this world. That's why I could endure everything. I wanted to send money to the family."

Jiyun worked hard, believing that the director would reward her for her good performance. Holding on to the promise that she would be able to contact her family, and send money back to them, she was soon bringing in more money than the other girls in the house.

"I wanted to be acknowledged by the director, and I wanted to contact my family. I thought I would be the first girl to be released from this work if I was the best in the house."

She would sometimes sleep for only four hours a night, in order to hit the daily target of $177 (£140). She was desperate to earn money for her family.

At times Jiyun would even console Mira, telling her not to rebel but to try to reason with the director.

"First, work hard," she would tell Mira, "and if the director doesn't send you home afterwards, then you can reason with him."

Jiyun says that during the years she was earning more than the other girls, the director favoured her a lot.

"I thought he genuinely cared for me. But on the days my earnings went down, the expression on his face would change. He'd tell us off for not trying hard, and doing other bad activities such as watching dramas."

All of Jiyun's possessions after escaping from the apartment

The apartment was closely guarded by the director's family. His parents slept in the living room and kept the entrance door locked.

The director would deliver food to the girls, and his brother who lived nearby came every morning to empty their rubbish.

"It was a complete confinement, even worse than a prison," says Jiyun.

The North Korean girls were allowed outside once every six months, or if their earnings were high enough, once a month. In those rare moments, they did shopping or went to get their hair done. But even then, they were not allowed to talk to anyone.

"The director walked very close to us like a lover, because he feared we would run away," says Mira. "I wanted to walk around as I wished but I couldn't. We weren't allowed to speak to anyone, even to buy a bottle of water. I felt like a fool."

The director had appointed one of the North Korean women in the apartment to be a "manager", and she kept an eye on the rest when the director was away.

All of Mira's possessions after escaping from the apartment

The director promised Mira that he would marry her to a good man if she worked hard. He promised Jiyun he would let her contact her family.

When Jiyun asked him to release her, he told her that she would need to earn $53,200 to pay for her trip. He then told her that he was unable to release her because he could not find any brokers.

Mira and Jiyun never saw the money they earned through their sexcam work.

The director initially agreed to give them 30% of the profits, and they were to receive this when they were released.

But Mira and Jiyun became more and more anxious as they realised they might never be free.

"Killing myself is not what I would normally think about, but I tried to take a drug overdose and tried to jump from the window," says Jiyun.

The years went by - five for Mira and eight for Jiyun.

Then a sexcam client of Mira's, who she had known for three years, took pity on her. He put her in touch with Pastor Chun Kiwon, who has been helping North Koreans defect for the past 20 years.

The client also remotely installed a messaging application on Mira's computer, so that she could communicate with the pastor.

Pastor Chun Kiwon receives a text to confirm Mira and Jiyun are safely over the Chinese border

Pastor Chun Kiwon is well-known among North Korean defectors. North Korean state TV frequently attacks him, calling him a "kidnapper" and a "con-man".

Since setting up his Christian charity Durihana in 1999 he estimates he has helped about 1,200 defectors to safety.

He receives two or three rescue requests a month, but he found Mira and Jiyun's case particularly distressing.

"I've seen girls who've been imprisoned for up to three years. But I've never seen a case where they've been locked up for this long. It really breaks my heart."

A North Korean state broadcaster discusses Pastor Chun

Chun claims the trafficking of female defectors has become more organised and that some North Korean soldiers guarding the border are involved.

The trafficking of women is sometimes referred to as the "Korean pig trade" by the locals living in the border region of China. The women's price can range from hundreds to thousands of US dollars.

Although official statistics are hard to obtain, the UN has raised concerns about high levels of trafficking of North Korean women, external.

The US State Department's annual Trafficking in Persons Report has consistently designated North Korea as one of the worst human trafficking nations, external.

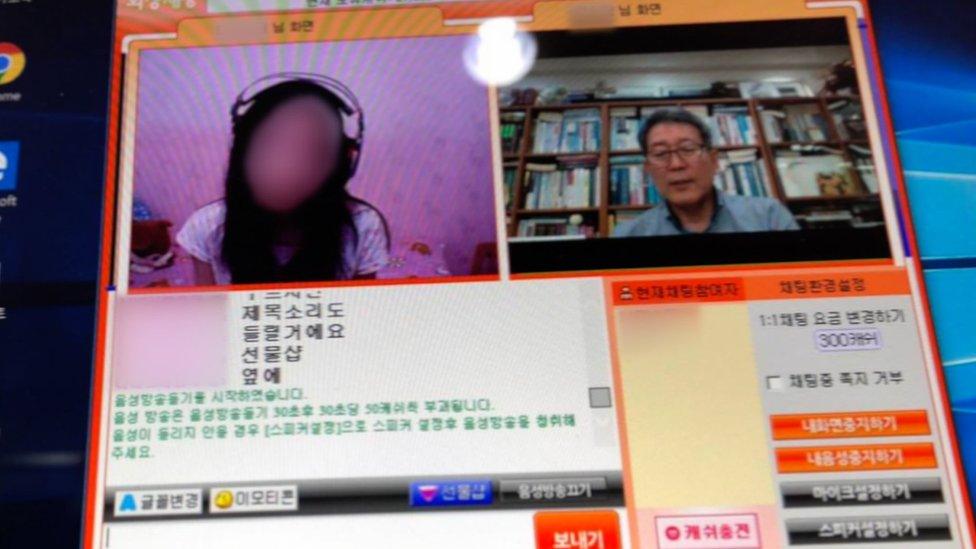

Pastor Chun Kiwon talks to Jiyun via the sexcam site

Over the course of a month, Chun kept in touch with Mira and Jiyun on the sexcam site, posing as a client. That way, the girls could pretend they were working while planning their escape.

"Usually imprisoned defectors are not aware of their location because they are taken to an apartment blindfolded or at night. Luckily, they [Mira and Jiyun] knew that they were in Yanji and they could see a hotel sign outside." he says.

Working out their exact location from Google Maps, Chun was able to send a volunteer from his organisation Durihana to scout out the apartment ahead of the escape.

The main routes taken by defectors wishing to escape North Korea and seek asylum in South Korea

Getting out of China is dangerous for any defector.

Most want to get into a third country, and to a South Korean embassy, where they will be granted a flight back to South Korea and asylum.

But travelling across China without ID is dangerous.

"In the past, defectors could get away with travelling with fake ID. But these days, the officials carry around an electronic device which can tell whether the ID is real or not," explains Chun.

After escaping from the apartment, Jiyun and Mira began their long journey across China with the help of Durihana volunteers.

Without any ID they could not risk checking into a hotel or hostel, and so were forced to sleep on trains or spend sleepless nights in restaurants.

On the last day of their journey in China, after enduring a five-hour climb up a mountain, they finally crossed the border and entered a neighbouring country. The route and the country they entered cannot be named.

Jiyun's hands marked by scratches after a five-hour mountain ascent over the Chinese border

Twelve days after escaping from the apartment, Mira and Jiyun met Chun for the first time.

"I think I'm perfectly safe only when I receive citizenship in South Korea. But just meeting pastor Chun made me feel safe. I cried at the thought of having found freedom," says Jiyun.

Together, they travelled by car for a further 27 hours to the nearest South Korean embassy.

Chun says some North Koreans find the final part of their journey particularly difficult to bear, unused as they are to car travel.

"The defectors often get car sick and sometimes faint after vomiting so much. It's a hellish road, travelled by those seeking heaven."

Just before arriving at the embassy, Mira smiles nervously and says she feels like crying.

"I feel like I've come out of hell," says Jiyun. "Many feelings come and go. I may never see my family again if I go to South Korea and I feel guilty. That was not my intention of leaving."

Together the pastor and the young women entered the embassy gate. A few seconds later, only Chun returns. His job is done.

Mira and Jiyun will be flown directly to South Korea, where they will undergo a rigorous screening process by the national intelligence service to make sure they are not spies.

Then they will spend up to three months at the Hanawon resettlement centre for North Koreans, where they will be taught practical skills to adjust to their new life in South Korea.

Defectors learn how to do grocery shopping, how to use a smartphone, are taught the principles of the free market economy and receive job training. They can also receive counselling. Then, they will become official citizens of South Korea.

"I want to learn English or Chinese so I can become a tour guide," says Mira when asked about her dreams in South Korea.

"I want to live a normal life, drinking coffee in a cafe and chatting to friends," says Jiyun. "Somebody once told me that the rain will one day stop, but for me, the monsoon season lasted for so long that I forgot the sun existed."

Now safely over the border Mira (L) and Jiyun (R) look back towards China

- Published8 January 2019

- Published3 January 2019

- Published2 January 2018