Trump's withdrawal from Afghanistan ignores a dangerous threat

- Published

Afghan security forces respond to reports of a suicide attack in Kabul earlier this month

Senior British officers in Afghanistan have long feared the decision of US President Donald Trump to wind down America's mission in the country.

One told me they used to talk about "the tweet of jeopardy", which they said might come at any time from @realDonaldTrump, external. When I told another officer about the resignation of US Defence Secretary Jim Mattis, he replied in typical military fashion: "Bugger."

It seems that the US's closest allies may not have known about the prospect of troop withdrawal in Afghanistan. Before the news broke, I interviewed the head of the armed forces, General Sir Nick Carter, who was in the capital, Kabul, to see troops before Christmas.

With lower US engagement, the international coalition itself could be at risk.

When I stayed at the NKC (New Kabul Compound) military base, which has a British commander, it was clear that the infrastructure was provided by the Americans. To bring back 7,000 US troops in the coming weeks was described to me by a British officer as "precipitous".

The US move is all the more surprising given the recent spike in violence in Afghanistan, which has been prompted in part by elections and by ongoing peace negotiations, with each side trying to assert its strength.

UK armed forces chief believed US was "committed" in Afghanistan

British soldiers from the Quick Reaction Force told me about being called out just three weeks ago to reports of a suicide bomb followed by an attack by four gunmen on the base of security firm G4S in Kabul. They ferried injured people to the airport.

That attack was carried out by Taliban militants, but international forces now face dangers from so-called Islamic State (IS) too. The commander of British forces in Afghanistan told me that IS was "a real threat" and has carried out attacks on soft targets in the capital.

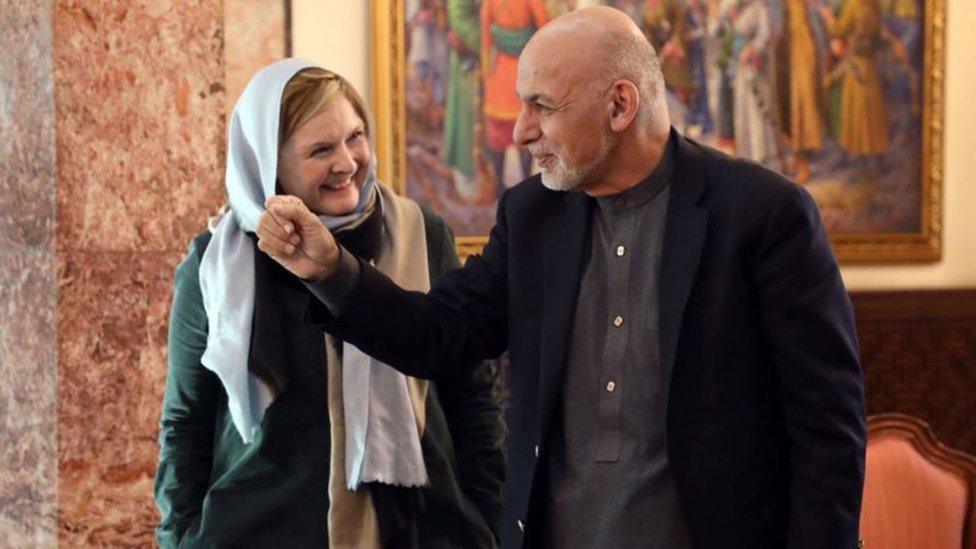

When I went to interview Afghan President Ashraf Ghani at his palace headquarters, he said he had been warning of the risk from IS - or Daesh, as he calls them - for years.

Afghan President Ashraf Ghani told Martha Kearney he was fully aware of the risk posed by IS

This cerebral man, a former anthropologist who worked at the World Bank, is an unusual politician. Mr Ghani showed me the desk he had personally found in an old store room which belonged to a reformist king of Afghanistan, an important symbol for him.

After our interview he was hosting a symposium on a Pashtun warrior poet. Quite a hinterland. But Mr Ghani is capable of extreme pragmatism, appointing a controversial warlord, General Abdul Rashid Dostum, as his vice-president.

Gen Dostum was forced to leave the country under a cloud. The president told me he wouldn't be on the ticket for next April's elections, but he didn't deny appealing for his support.

This is my fourth visit to Afghanistan. When I visited the presidential palace back in 2002, we were able to walk down tree-lined avenues through the diplomatic area. Now the "Green Zone" is a maze of concrete blast walls, barbed wire and check points, a sign of how dangerous the centre of Kabul has become.

Helicopters are used for transportation as Kabul has become increasingly dangerous

We had to travel to many locations by Puma helicopters - described by the soldiers as Kabul taxis - or in Foxhound armoured vehicles.

It is the Afghans who bear the brunt of the violence. Eight thousand civilians were killed in the first nine months of this year. Since 2015, nearly 30,000 police and army recruits have been killed.

With such a high number of casualties it is easy to be pessimistic, but the British troops are clearly proud of their role in Afghanistan. They mentor instructors at the Afghan officer training academy. A recent female cadet was invited to attend Sandhurst, the UK's prestigious military academy.

The other UK role, force protection, means that they are responsible for the safety of advisers like doctors and nurses who have come to Afghanistan to help rebuild the war-torn country.

There are presidential elections in Afghanistan next April, and now the prospect of further US troop withdrawals, which could ultimately lead to the end of the international coalition here.

Gen Carter maintains that progress has been made in creating the conditions for peace. But this is a volatile time in a country inured to instability.

- Published21 December 2018

- Published2 December 2018

- Published14 September 2018

- Published12 August 2022

- Published10 March