Trump-Kim summit: What North Korea can learn from Vietnam's women

- Published

Entrepreneurs like Ms Thanh are the lifeblood of Vietnam's economy

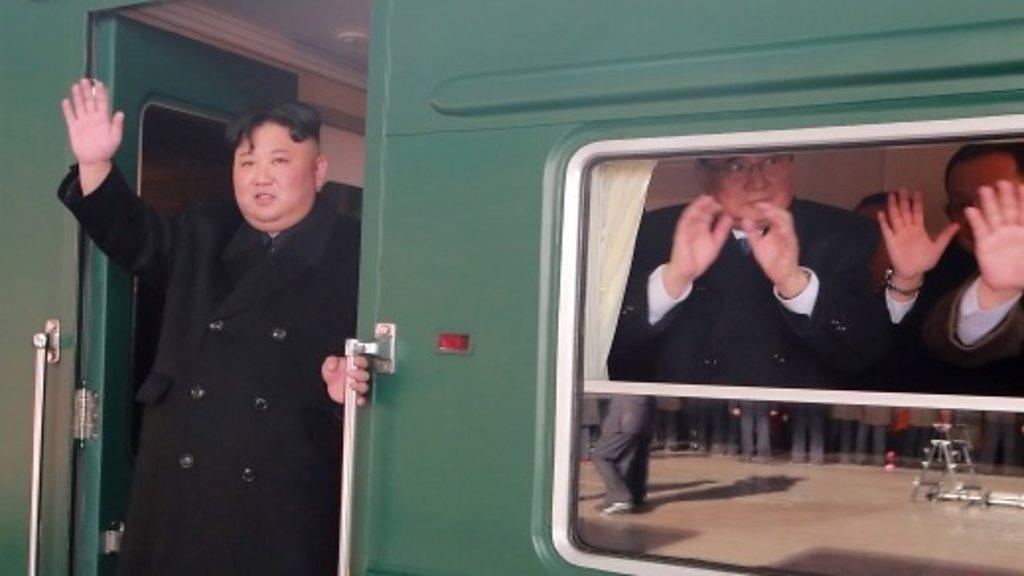

As US President Donald Trump and North Korea's leader Kim Jong-un prepare for a historic summit in Vietnam, the BBC takes a look at how the host country could act as a role model for North Korea's future.

Duong Thi Thanh has built a global textile business from a tiny room in the backstreets of Hanoi with what is essentially several large buckets of drunk bacteria.

She makes traditional indigo tie-dye clothing using techniques that many thought had been lost. First, she employed workers in a small mountain town called Sapa to collect the indigo plant leaves. She then ferments the leaves in plastic buckets using rice wine, which she pours in every night before giving it a stir.

"The bacteria always sleep," she said with a giggle when I visited her workshop. "They don't want to work as they're very lazy. But they like to drink."

She bends down and cups the water from the bucket in her hand. It was a weak shade of blue with hints of green. But as she stirred in the alcohol it changed to a real blue hue. "See, the wine wakes them up," she said.

She then pushes a piece of bright white cotton into the blue liquid - the start of a ten-day process to turn this cloth into a unique piece of indigo dyed clothing.

Duong Thi Thanh's fabric is sold all over the world

Behind her, sewing machines buzzed as her staff made cushion covers, long cotton dresses and scarves. Further back, I could hear the hiss from an iron on the production line.

When Ms Thanh started her business she struggled to make a few hundred metres of fabric a year. 24 years later, her customers are ready to order online and come from all over the world. One of her biggest markets is in Australia and Japan.

From black market to international trade

Ms Thanh is just one of thousands of female entrepreneurs who are the lifeblood of the Vietnamese economy.

Restrictions on running an enterprise were lifted in the 1980s and the country was opened up to international trade and investment. Women who had run small businesses in the black or grey markets to supplement their household income could operate legally.

There are now more female business owners in Vietnam than anywhere else in Asia and they own many of the small to medium businesses which make up 40% of the country's GDP.

There is a lesson here for thousands of North Korean households where women have become the main breadwinners.

Small to medium businesses make up 40% of Vietnam's GDP

Men still call the shots in what is a very patriarchal society, but women are making the money as informal markets continue to spring up across the country.

A famine in the 1990s killed hundreds of thousands of people and some lost faith in the state's ability to distribute food and wealth. They looked for other ways to survive.

Women as the main breadwinners

Often men had to continue working in state funded jobs or in the military, so it was left to the women to find other ways to earn an income. One South Korean government survey once estimated that women earn more than 70 percent of a household's income in North Korea.

Jessie Kim was one of them.

Her mother died when she was 11 years old and her father neglected her. She would go days without food, she said. So she foraged berries and herbs in the mountains and sold them to make a little money.

Then she spotted a gap in the market as she watched men gathering to drink one night. Aged just 12, she went to the city and bought Korean rice wine called soju. She diluted it and sold it for a profit.

"If I want to survive in North Korea, then I have to earn money. I don't want to die," she said.

Jessie Kim escaped North Korea after a childhood selling alcohol at local markets

She earned enough to help buy food for her grandmother. She defected to South Korea in 2014, and her drive to run a business remains - she is studying economics at university.

The emergence of these markets could have a lasting effect on politics in North Korea.

Van Tran Ngoc helped train budding North Korean female entrepreneurs in Vietnam with the not-for-profit organisation Choson Exchange. She was surprised by how engaged they were. "In many ways, they remind me of businesswomen in Vietnam," she said.

"Both seem quiet at first, but are very eager to learn and hardworking. They didn't take their break between workshops, and spent all of the time trying to learn more. When I brought them around Hanoi, they constantly asked me about different business models, and how Vietnam transformed the economy after the wars."

Responsibility and ambition

She sees a lot of comparisons between Vietnamese and North Korean businesswomen. Both are in charge of the finances for their families and that is their main motivation.

"One common thing I've seen is that they dream big and are not shy of sharing their ambitions," she said.

For Ms Thanh, that dream is quality over quantity. There is a lot of demand for her products but she wants to avoid moving towards mass production.

Could crickets help to solve world food shortages?

By the time Vietnam's economy opened up to the outside world, China and India had already grabbed a large share of the textile market, so the Vietnamese looked for smaller, lucrative buyers.

I asked Ms Thanh what advice she has for those in North Korea where textiles have become the second largest industry in the country.

"Don't think about the cheap market," she said. "Everyone can copy you. You need to make something that's special. And you need to learn about the International market."

Hundreds of thousands of jobs in North Korea depend on both small markets and on textiles. So much focus over the next few days of this summit between US President Trump and the North Korean leader will be the big business offers for Kim Jong-un.

But just as the Vietnamese have proved, it is the small to medium-sized businesses, run mostly by women, that can make all the difference.

- Published5 September 2023

- Published24 February 2019

- Published24 February 2019

- Published23 February 2019

- Published20 February 2019

- Published18 February 2019

- Published9 February 2019

- Published6 February 2019

- Published25 December 2018

- Published16 October 2018

- Published26 September 2017