Akihito and Japan's Imperial Treasures that make a man an emperor

- Published

The three Treasures have their origins in the legend of Amaterasu - the sun goddess

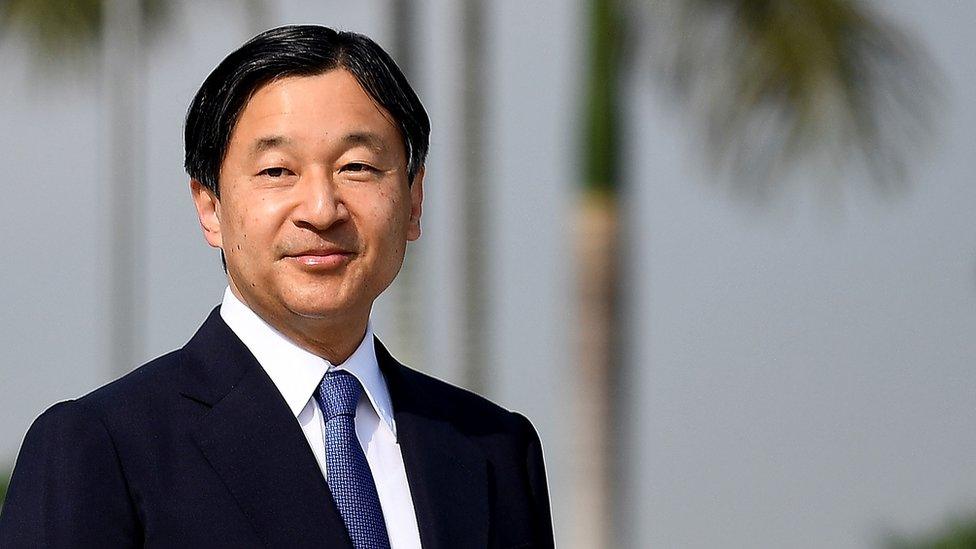

On 1 May, Crown Prince Naruhito will ascend the Chrysanthemum Throne after his father abdicates, becoming the new emperor of Japan.

Both the abdication and accession will involve deeply symbolic Shinto ceremonies, and central to them will be three objects - a mirror, a sword and a gem - known as the Imperial Treasures or Regalia.

The origins and whereabouts of the mysterious objects are shrouded in secrecy, but myths about them are peppered throughout Japanese history and pop culture.

Why are the Imperial Treasures so important?

Japan's unofficial national religion, Shinto, places huge importance on ritual to maintain a connection with the past and with spirits which intervene in human lives.

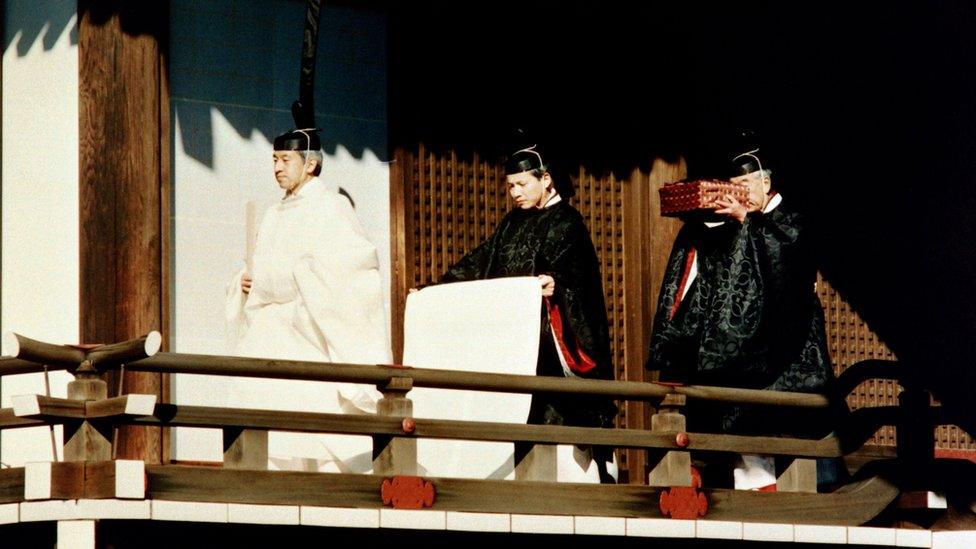

The treasures feature prominently in the accession ceremony but are never seen

The Imperial Treasures are part of this. They are said to have been passed down from the gods through generations of emperors seen as their direct descendants. In the absence of an imperial crown, the treasures act as the symbol of imperial power.

But the treasures are so sacred, they are kept hidden from the world.

"We do not know when they were made. We have never seen them," Prof Hideya Kawanishi from Nagoya University told the BBC.

"Even the Emperor has never seen them."

In fact they won't even be at the coronation - replicas (which still won't be seen) will be used, and the originals - if they are even that - will stay at their shrines around the country.

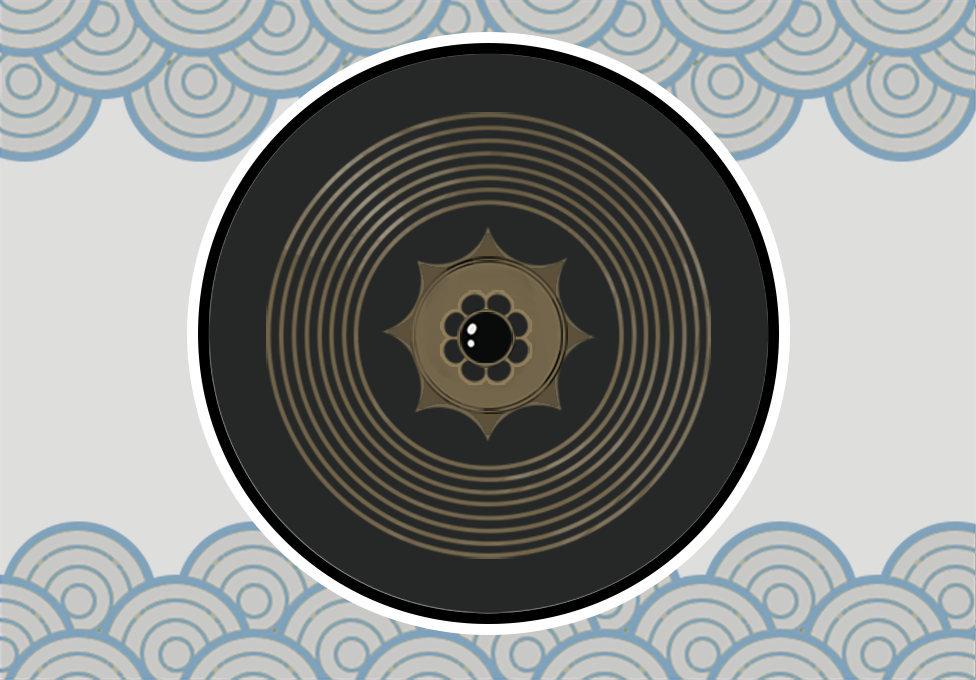

Yata no Kagami - the sacred mirror

The mirror, which may be more than 1,000 years old, is believed to be kept at the Ise Grand Shrine in Mie prefecture. According to Shinsuke Takenaka at the Institute of Moralogy - a Japanese body which researches ethics and morality - it is considered the most precious of the treasures.

It was the only one of the treasures which did not feature in the last enthronement in 1989.

In Japanese folklore, mirrors are said to have divine power and to reveal truth. In the imperial ceremonies, Yata no Kagami - or eight-sided mirror - represents the wisdom of the emperor.

According to the Kojiki, the ancient written record of Japanese history and legend, the Yata no Kagami was made by the deity Ishikoridome.

After the sun goddess Amaterasu fought with her brother Susanoo, the god of the sea and storms, she retreated to a cave taking the light of the world with her.

Susanoo arranged a party to lure her out, and Amaterasu was dazzled by her own reflection in the mirror. They repaired their squabble, bringing light back to the universe.

The mirror and the other treasures eventually made their way to Amaterasu's grandson, Ninigi.

According to the legends, says Mr Takenaka, the goddess told Ninigi: "Serve this mirror as my soul, just as you'd serve me, with clean mind and body."

Ninigi is believed to be the great-grandfather of Jimmu, who legends say became Japan's first emperor in 660 BC.

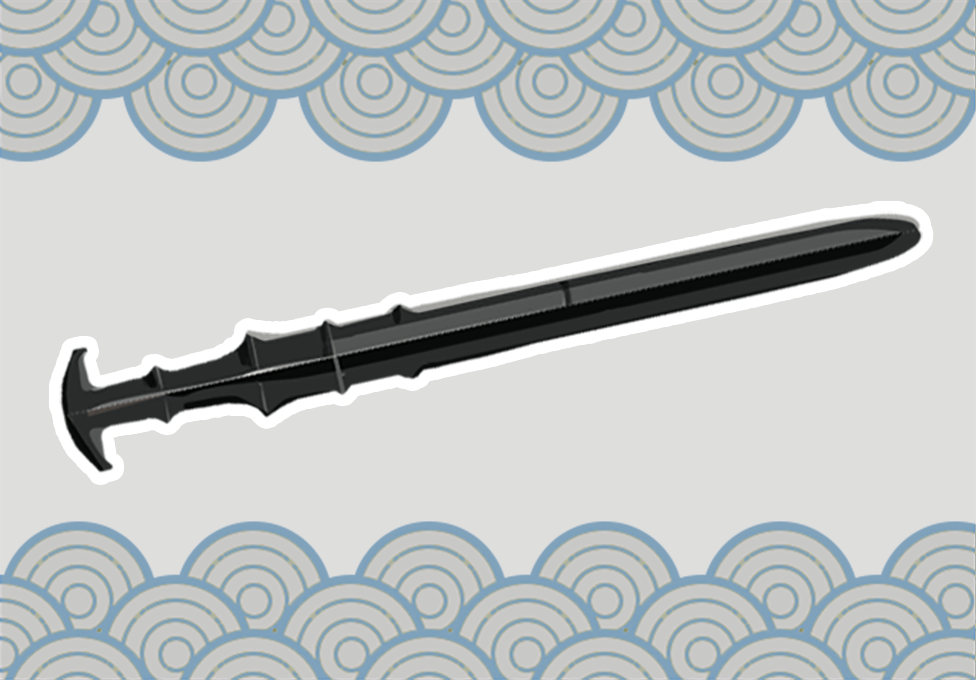

Kusanagi no Tsurugi - the sacred sword

The location of the Kusanagi no Tsurugi - or grass-cutting sword - is not clear, but it may be at the Atsuta Shrine in Nagoya.

Legend says it grew in the tail of an eight-headed serpent that was devouring the daughters of a wealthy family.

The father appealed to Susanoo for help, promising marriage to his last uneaten daughter if he could rid them of the snake. Susanoo tricked the serpent into getting drunk, then cut off its tails, finding the sword.

But he didn't have it for long - it too was used in his efforts to make up with his sister, Amaterasu.

The sword represents the bravery of the emperor. Because so little is known about it and where it is kept, some question whether the sword actually still exists.

It's certainly been kept in secret - one priest who reported having seen it in the Edo period (some time between the 17th and 19th Century) was banished.

There are rumours it may have been lost at sea during a 12th Century battle, but Mr Takenaka says that may itself have been a copy, and that a duplicate of that, kept at the palace, is used for coronations.

When Emperor Akihito came to the throne in 1989 he was given a sword said to be Kusanagi no Tsurugi. But the box he was given remained unopened.

Yasakani no Magatama - the sacred jewel

A magatama is a type of curved bead which started being made in Japan around 1,000 years BC. Originally decorative, they started taking on symbolic value.

According to the legend, the Yasakani no Magatama was part of a necklace made by Tamanooya-no-Mikoto. It was worn by Ame-no-Uzume, the goddess of merriment, who played a central role in the efforts to lure Amaterasu from her cave.

She performed an extravagant dance, wearing the beads, to cause a commotion and attract the sun goddess's attention.

Whatever its origins, the Yasakani no Magatama, made of green jade, may be the only surviving "original" among the three treasures.

It is housed in the imperial palace in Tokyo and in the enthronement ceremony, represents the benevolence required of an emperor.

Do Japanese believe in the treasure?

While Japan's emperors trace their lineage to Amaterasu, they no longer claim to be gods themselves - Emperor Hirohito renounced his divine status after Japan's defeat in World War Two.

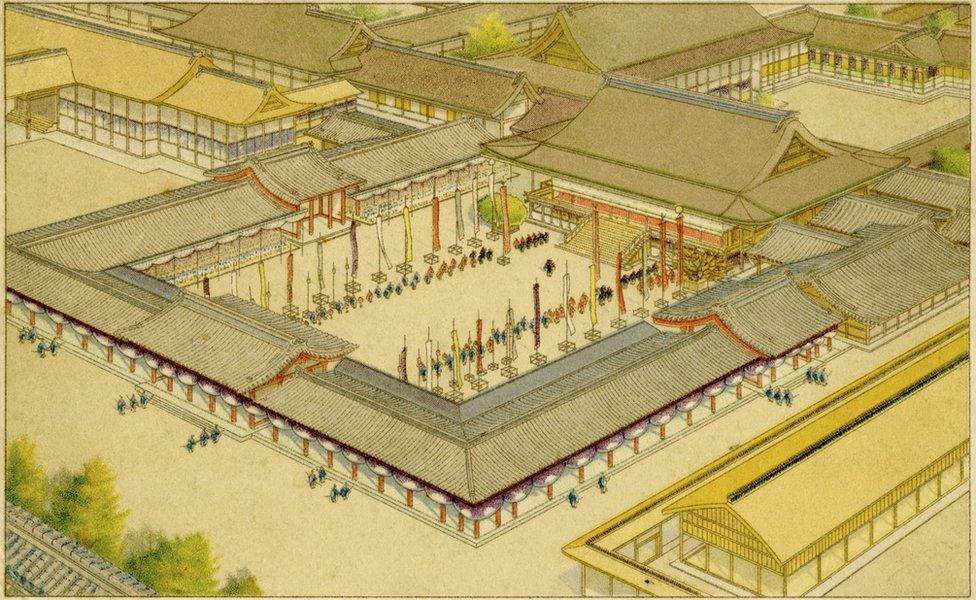

A depiction of the coronation of Emperor Taisho in 1912 in Kyoto

Prof Kawanishi says there are many in Japan who still think of the objects as being imbued with divine power, but that many people "think of them now more as ornaments, a bit like a crown in other monarchies".

They're largely important because they "show the mystery of the emperor", he says, and as a "symbol that the system has continued for a long time".

Mr Takenaka says there is also a view among scholars that the items represent the fusion of Japan's ancient indigenous groups with new arrivals.

Based on that theory, he says, the three treasures are a symbol the emperor should unite the ethnic groups without discrimination.

But he adds that in the 20th Century, the term "three treasures" also took on a slightly more practical meaning, becoming the phrase for the three things Japanese people felt they could not live without: a TV, a refrigerator and a washing machine.

Additional reporting by Mariko Oi

- Published1 May 2019

- Published1 May 2019

- Published30 April 2019

- Published30 April 2019

- Published30 April 2019

- Published26 April 2019