Akihito: The Japanese emperor with the human touch

- Published

On a beautiful spring morning last week, I stood on a street corner on the western outskirts of Tokyo. For hundreds of metres in each direction, the road was lined, three-deep, with eager, excited faces. Then, with almost no warning, a large black limousine approached over a bridge, motorcycle outriders on either side.

As the car slipped by, for a few brief moments, we could see Emperor Akihito and Empress Michiko leaning forward waving gently. A ripple of applause and waving of plastic flags from the crowd, and they were gone.

To me, it all seemed a little anti-climactic. And I was not alone. Nearby an elderly lady was chastising a policeman.

"Why did they go so fast?" she demanded to know. "Usually they drive much slower than that. We hardly got any chance to see them."

The policeman smiled patiently. Clearly, he had no control over the speed of the motorcade.

I had expected a few hundred hardcore groupies to turn out for this final visit by the royal couple to the imperial tombs. Instead there must have been 5,000 or more. Some were dabbing away tears as the crowds began to disperse.

"I am grateful for what they have done for the Japanese people," said a lady wearing an exquisite spring kimono. "I waved at them with the feeling of deep gratitude for all these years."

"I am really moved," said her friend. "I hope he can rest and have a peaceful life after so many years on duty."

Kaoru Sugiyama, wearing a large floppy sunhat, had also come with a group of friends.

"I am not from the generation that experienced the war," she said. "But when you look back, it is the emperor that has kept peace in Japan through his reign. So I wanted to come and see him on his last visit, to show my gratitude. I wanted to tell him, 'thank you'."

What is it that Emperor Akihito has done to inspire such feelings?

The consoler in chief

In January 1989, upon his father's death, Emperor Akihito succeeded to the Chrysanthemum Throne.

It was an optimistic time. Japan was rich, at the height of its post-war economic boom. Sony was about to buy Columbia Pictures and Mitsubishi was on the verge of buying the Rockefeller Center in New York. The talk, in much of the world, was of Japan the new "superpower".

Japanese Emperor Akihito in ceremonial outfit, 1990

But a year into his reign, calamity struck. The asset bubble burst and the Tokyo stock market collapsed, losing 35% of its value. Nearly 30 years on, Japanese stocks and land prices are still below 1990 levels.

For most Japanese people the Heisei era - the name means "achieving peace" - has been one of economic stagnation. It has also been one marked by tragedy.

In January 1995, a 6.9 magnitude earthquake ripped through the city of Kobe, toppling buildings and motorway viaducts and starting fires that burned for days, turning the sky above the city black. Around 6,000 people were killed.

In 2011, an even more devastating quake hit off the north-east coast. At magnitude 9, it was the fourth largest earthquake ever recorded. It unleashed a giant tsunami that smashed into the coast of northern Japan, sweeping away whole towns and killing nearly 16,000 people.

It was after that second disaster that Emperor Akihito did something no emperor had ever done before. He sat down in front of a TV camera and spoke directly to the Japanese people.

Two weeks later, the emperor and empress arrived at an evacuation centre in a stadium outside Tokyo.

People were camped on the floor, a few meagre possessions piled around them. Most had fled the radiation cloud ejected from the damaged nuclear plant in Fukushima. They had left almost everything behind, unsure of when, or if, they would be able to return to their hometowns.

The emperor and empress knelt on the ground with each family in turn, talking to them quietly, asking questions, expressing concern.

Emperor Akihito and Empress Michiko talk with evacuees from the 2011 earthquake and tsunami

Japanese people had never seen an emperor behave like this before. To conservatives it was a shock. This is not how the direct descendant of the sun goddess Amaterasu should behave. But many more Japanese were deeply moved by the emperor's very human show of empathy.

"He has moral authority," says Prof Jeff Kingston, from Temple University in Tokyo. "And he's earned it. He is the consoler in chief. He connects with the public in a way his father never could.

"So he goes to shelters and not like a politician going for a photo op, to wave and leave. He sits with people and drinks tea and engages in conversation in a way that was unthinkable in the pre-1945 era."

The sins of the father

Emperor Akihito does not have the appearance of a revolutionary. He is small, modest and softly spoken. His words and actions are tightly constrained by Japan's post-war constitution and, while under international law the emperor is usually recognised as the head of state, in Japan his role is defined as a much more vaguely worded "symbol of the state and unity of the people".

He is banned from expressing any political opinion.

And yet within the tight straitjacket of his ceremonial role, Emperor Akihito has managed to do some remarkable things.

The first thing you need to remember is that Akihito is the son of Hirohito, the god-like emperor who reigned over Japan during its nearly 15-year rampage across Asia in the 1930s and 40s. Akihito was 12 when the war ended with the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Emperor Hirohito and Prince Akihito reading a newspaper

At some point in his education, some say under the influence of his American tutor Elizabeth Gray Vining, Akihito became a confirmed pacifist, and he remains so today. He has told people his greatest contentment comes from knowing that during his reign, not a single Japanese soldier has been killed in war or armed conflict.

The emperor has made it his job to reach out to Japan's former enemies and victims. From Beijing to Jakarta, Manila to Saipan, he has sought to heal the wounds inflicted under his father.

"He created a new role for the emperor, and that is the nation's chief emissary for reconciliation, criss-crossing the region, making gestures of atonement and contrition. Basically, trying to heal the scars of wartime past," says Prof Kingston.

Wedding of Prince Akihito and Princess Michiko, 1959

In the 1990s that was relatively uncontroversial. Japanese politicians encouraged the emperor, arranging a landmark trip to China in 1992. But as he has grown older, Japanese politics has moved dramatically to the right.

The old "apology diplomacy" is out of favour, as is pacifism. The current prime minister, Shinzo Abe, had vowed to rid Japan of its pacifist constitution. He and others on the right want to bring back patriotic education, and expunge what they call the "historical masochism" of the post-war era.

Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe walks past Emperor Akihito and Empress Michiko during an annual memorial service for war victims, Tokyo, 2014

In subtle, but determined ways, Emperor Akihito has repeatedly shown his disdain for the revisionists. In 2015, on the 70th anniversary of the end of the war, Mr Abe gave a speech.

"He basically said that the peace and prosperity we enjoy today is owing to the sacrifice of the three million Japanese who died during the war," says Prof Kingston.

"The next day, Akihito was having none of that. He made a speech saying the prosperity we enjoy today is down to the hard work and sacrifice of the Japanese people after the war."

To the millions of Japanese watching on TV, it was an unmistakable slapdown.

On another occasion at a royal garden party in Tokyo, a right-wing member of the Tokyo metropolitan government proudly told the emperor that he was in charge of making sure all teachers stand and face the flag when they sing the national anthem.

The emperor gently but emphatically admonished the bureaucrat.

"I am in favour of individual choice," he said.

The long farewell

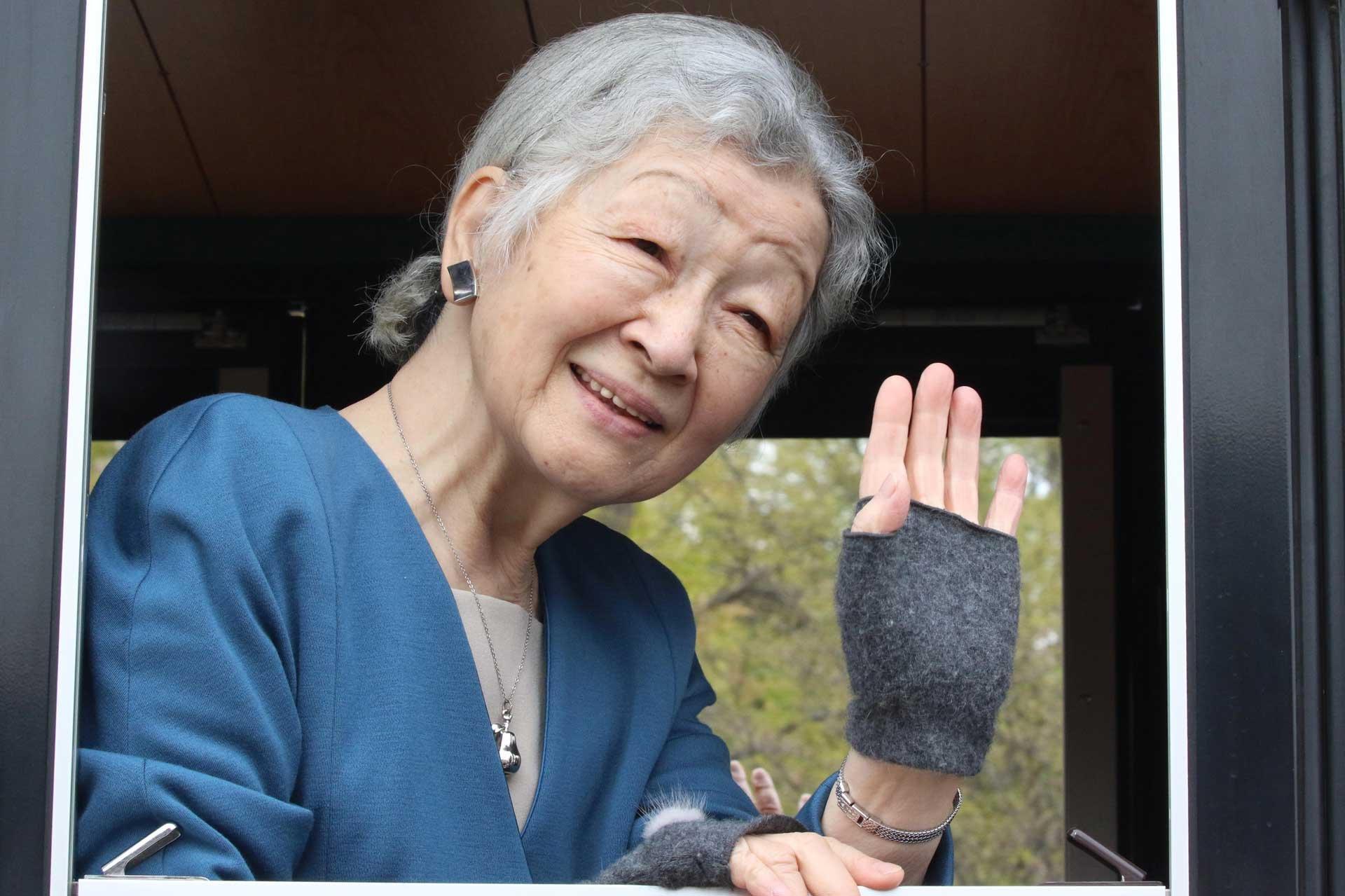

Throughout his reign, the emperor has been inseparable from his most important companion and advisor, Empress Michiko. She was born a commoner, and has, at times, found life in the imperial household extremely hard. In 1993, the empress collapsed from mental exhaustion and for two months she lost the ability to speak.

Empress Michiko married Emperor Akihito in April 1959

Writing recently, she spoke of her awe at her husband's resolve.

"His duties required of him in his role are the utmost priority at all times and personal matters take second place," she wrote, "and that is exactly how he has lived these nearly 60 years."

But for some time, Emperor Akihito has been in declining health. He has had cancer and major heart bypass surgery. Those close to him say he has become increasingly worried that poor health would incapacitate him and make it impossible for him to carry out his official duties.

As far back as 2009, the emperor began quietly agitating to be allowed to hand the throne to his son. This is no easy task.

The post-war constitution makes it clear emperors are to serve "for life". And so, according to Prof Takeshi Hara, of Japan's Open University, the politicians ignored the emperor's requests.

"Over the course of nine years, none of the governments sympathised with the emperor's feelings," he says. "They felt that if they complied with the emperor's desire to abdicate, this would show the emperor has power to make important decisions, and that is against the constitution."

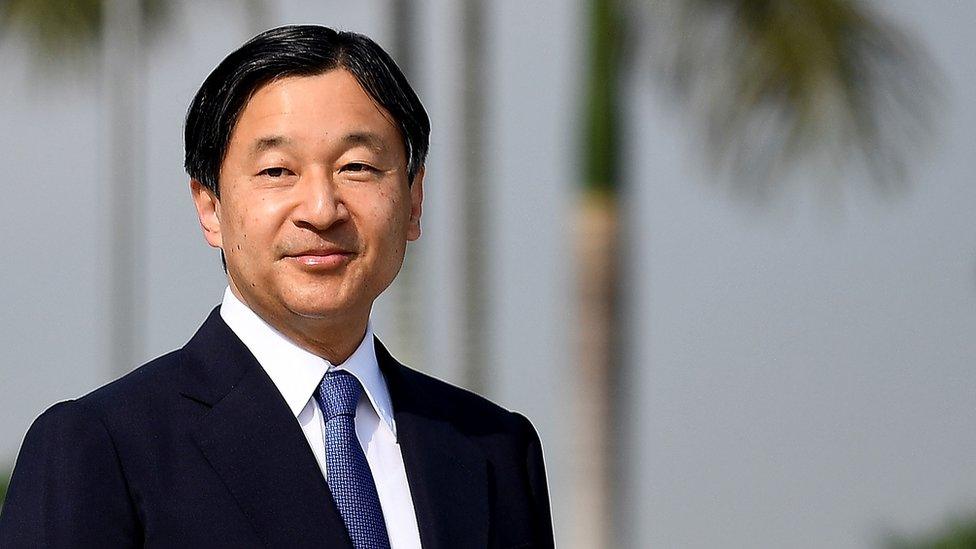

Prince Naruhito and Princess Masako with their pet dog Yuri.

It is a very Japanese conundrum. In increasing desperation, Prof Hara says the emperor and imperial household agency cooked up a scheme.

"The emperor and the Imperial Household Agency were growing more and more impatient," he says. "So someone in the Household Agency leaked the information to NHK (Japan's national broadcaster). Then NHK broadcast news of the emperor's request."

It was a huge scoop for Japan's national broadcaster and it broke the impasse. A month later the emperor went on TV for a second time to appeal directly to the Japanese people, explaining his wish to step down and hand the throne to his son.

Opinion polls showed the overwhelming majority of Japanese supported the emperor's wish. Mr Abe and the conservatives had no choice but to comply. It has taken nearly another two years, but now Emperor Akihito will finally be able to enjoy his retirement.

The country will officially begin a new era on 1 May, when Crown Prince Naruhito ascends to the Chrysanthemum Throne as the new emperor.

- Published27 April 2019

- Published1 May 2019

- Published26 April 2019