Indonesia election: Why one vote could put a thousand Indonesias at stake

- Published

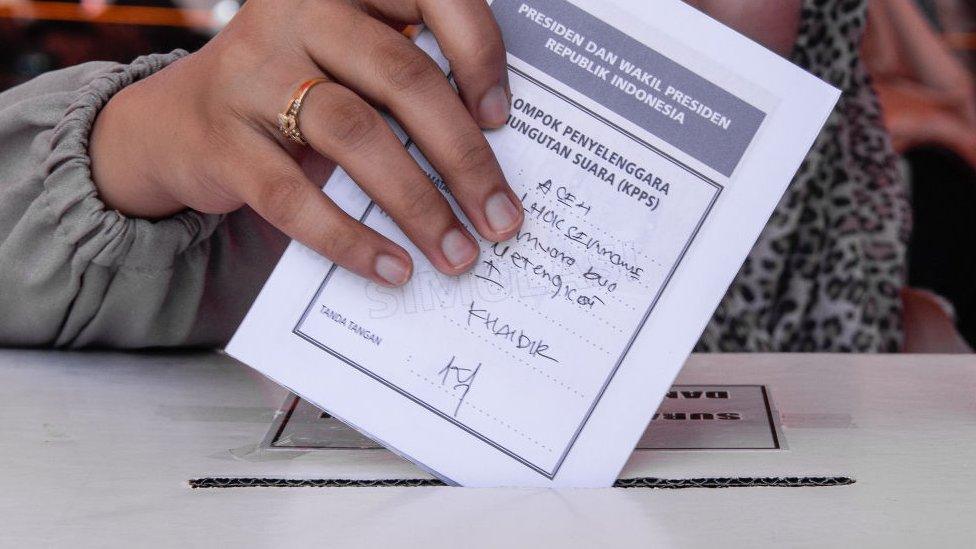

A woman votes during Indonesia's pre-election drill

While the world marvels at Indonesia's staging of the most complex single-day election in history, the real challenge for the country runs far deeper.

A rising tide of intolerance could put the hard-won unity of the country with more Muslims than anywhere else on Earth - unique for being so geographically far-flung and culturally diverse - at real risk.

You often hear that Indonesia is a country of more than 17,000 islands, that it is multi-ethnic and multi-religious, but that really doesn't begin to capture the scale.

Indonesian President Joko "Jokowi" Widodo began his final election rally day speech by reading out a litany of names of different islands, speaking in many dialects to reach out to his supporters across this archipelago.

"Dari Sunda mana, sampurasun... Jawa Timur opo kabare rek. Dari Riau, Sumatera Barat, Jambi apo kabar?" ["People from Sunda, greetings to you....From East Java, how are you? From Riau, West Sumatra, Jambi, how are you doing?"]

Imagine the difficulty of governing a nation like this - from West to East it spans the distance between London and Baghdad, with three different time zones and hundreds of different ethnic groups and languages.

Indonesia is made up of over 17,000 islands

This is not just one Indonesia, it is a land of a thousand Indonesias - any Indonesian can tell you that, but growing up here and later as a correspondent and editor, I witnessed the struggle of the country's fledgling democracy to hold together such a diverse nation and forge a common consensus.

This election, while on the face of it a re-run of the 2014 face-off between Mr Widodo and his rival Prabowo Subianto, is also a test of whether that vision of Indonesia is still robust.

A potpourri of faiths

For the first time in a poll voters will not just elect a president, but also 245,000 legislative representatives vying for more than 20,000 seats - so it is going to be about much more than a personality and competence contest between these two men.

The founding fathers of this country acknowledged the many competing visions of Indonesia when they began the difficult task of governing after declaring independence from the Dutch in 1945, and attempted to unify these islands into one country.

With more Muslims here than anywhere else, Indonesia could have - after independence - chosen the path of an Islamic nation, and there was pressure for this.

In the end, the country opted for what is called Pancasila - the five principles - and the philosophy of Bhinneka Tunggal Ika - unity in diversity.

These have promoted and protected tolerance in Indonesia - where the right to practice five other faiths besides Islam is enshrined in the constitution.

This potpourri of faiths was bound into everyday lives. It was in the multitude of different religious deities - Hindu, Christian, Islam - in our family prayer room, and the different faiths my father's brothers chose to adopt - one Catholic, another Muslim, while the rest remained broadly Hindu.

Many religions are practised in Muslim-majority Indonesia

Islam in Indonesia has always been different from the Islam practised in Saudi Arabia, or South Asia, having been brought from the 11th century onwards by Muslim traders who wished to establish a trade in the rich array of spices found in the islands.

Before that, many parts of maritime South East Asia had been influenced by different traditions of Hinduism and Buddhism. Both religions left enduring legacies that shaped the culture of Muslims in Indonesia, while Bali remains majority Hindu to this day.

Underlying even these ancient faiths, were much older local ritual traditions that can be described as "animist", long woven into the tapestry of many Indonesian lives - if perhaps fading today.

Christianity, brought by Dutch colonisers, has also left its mark on Indonesia.

For the most part, the country has allowed these faiths to co-exist comfortably.

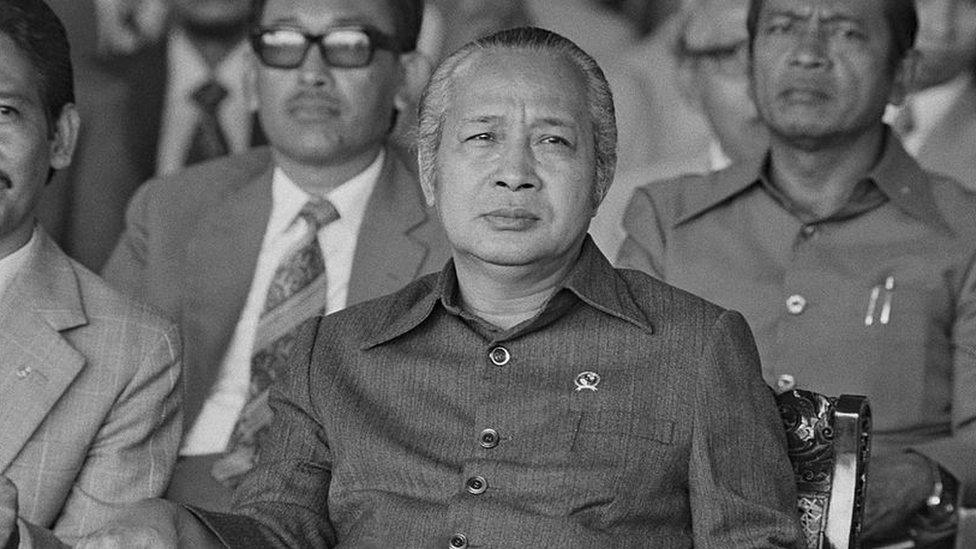

Part of that tolerance was brought about by force - under former President Suharto's three-decade-long authoritarian rule, political Islam was a threat that was quashed.

Ex-president Suharto ruled the country with an iron fist

When he stepped down in 1998, communal violence raised fears that the country would be Balkanised - split up into dozens of smaller countries - but that didn't happen.

Instead Indonesia forged a relatively smooth transition from dictatorship to its adopted moniker: a moderate Muslim nation and thriving democracy.

Rising intolerance

In recent years this reputation has come under threat because of what experts have identified as rising intolerance amongst hardline Muslim groups, and this is evident in the use of identity politics by both presidential candidates.

"Indonesia appears to be settling into a more divisive pattern of identity politics that risks stoking further intolerance and distracting from the debate about political, legal, and economic reforms."

Analysts say the turning point was the ousting of former Jakarta governor and Chinese Indonesian politician Basuki Tjahaja Purnama - known as Ahok - from power, under pressure from hardline Muslim groups.

Ahok was charged with blasphemy and spent 20 months in jail

Protests erupted on the streets of Jakarta, calling for him to step down and be charged with blasphemy, after he was accused of insulting Islam in a video widely circulated on social media. Mr Basuki, an ally of President Jokowi, said his comments were taken out of context.

He was eventually charged and convicted of blasphemy in 2017 and spent 20 months in prison.

Mr Widodo remained silent in the face of those protests and Ahok's subsequent imprisonment, partly because, analysts say, he was worried about being seen as anti-Muslim if he spoke out.

"The Ahok case was an example of politicians instrumentalising religion and identity on a much bigger scale," adds Mr Bland. "[Mr Widodo's] political opponents, including Mr Prabowo and Mr Sandiaga, saw the anti-Ahok movement as an opportunity to weaken the president ahead of the 2019 election."

Mr Widodo has been under pressure to beef up his religious credentials ever since he came to power in 2014.

His platform of inclusion and his common man politicking helped him to victory then, but Indonesia has changed in the last five years - and much like the rest of South East Asia it has become more socially conservative.

So in an effort to look "Muslim" enough, Mr Widodo has teamed up with 76-year-old cleric Ma'ruf Amin as his running mate, an uneasy pairing making for a very odd political couple.

Mr Widodo and his running mate Ma'ruf Amin (R), a prominent Islamic cleric

The opposition has also weaponised Islam and exploited the support of radical Muslim groups to win votes.

At the rallies of Mr Prabowo and Mr Sandiaga you can see the banners of conservative Islamic groups and Mr Prabowo has routinely whipped up emotions by arguing Muslims are being trodden on by the current government.

"This country is sick," he shouted at a recent rally in Jakarta.

"Muslim clerics and ulemas are being chased out of the country... The innocent who have expressed their opinions are being jailed in a country where freedom of expression is guaranteed by law."

But the Prabowo-Sandi team is quick to reject accusations of pandering to Islamists.

"Come on man, look at me," Mr Sandiaga tells me on the campaign trail in a suburb of Jakarta, dressed in his trademark baseball cap and jeans.

Presidential candidate Prabowo Subianto has teamed up with Sandiaga Uno (R) - who denies pandering to Islamists

"Do I look like a hardline Muslim to you? Come on. We believe Muslim voters want what everyone wants - a strong economy, good jobs and a strong Indonesia."

'Unity in diversity'

But while religious considerations have played a disproportionate role in this election, there are other pressures on Indonesia's pluralism.

Indonesia's tribal and far-flung communities will also be voting, and their priorities are altogether different.

Horses, boats and planes: Getting ballot boxes to Indonesia's remote villages

Issues like social inequity, the economy, and opportunities to improve their education and income are top of their minds - but not everyone will have the right to vote, even though they're eligible.

In Papua for instance, Indonesia's easternmost province, voters will be using the noken system, where tribal leaders will have the final say on who their tribe chooses as a candidate.

It's a system set up by the Indonesian election commission to reach the remotest communities - but one that might also be vulnerable to bribery and manipulation.

The Indonesian tribe who can't read so can't vote

In Sulawesi, recently hit by the twin disasters of a devastating earthquake and tsunami, voters often feel neglected and ignored by Java-centric governments and candidates - even though by some accounts they make up 14% of the electorate.

President Joko Widodo has tried to reach out to these other Indonesias by building infrastructure and development projects. That's gone some way to appease voters, but analysts say those demands will multiply after these polls, as Indonesians expect more from their leaders.

"Indonesian democracy is very much a work in progress," says Dewi Fortuna Anwar, a research professor at the Indonesian Institute of Sciences.

"We have been praised as the poster child of democracy... there's been a lot of complacency."

But Ms Anwar is also an optimist. She believes Indonesian values of pluralism are here to stay - if they are protected.

"To be a real Indonesian you have to believe in unity in diversity," she says. "That while Islam is the majority - we also have sizeable minorities."

As Indonesia matures, it will have to protect its delicate pluralism from the challenges of its hard-won democracy, where the majority voice will always be the most strident.

You could say that in this vote, a thousand Indonesias are at stake.

- Published12 April 2019

- Published17 April 2019

- Published12 April 2019

- Published14 April 2019

- Published16 April 2019