Sri Lanka attacks: The family networks behind the bombings

- Published

A statue amid debris at St Sebastian's Church in Negombo, Sri Lanka, following the Easter Sunday bombing

For many Sri Lankans, it was a horrific shock to learn that local Muslims could have been behind the suicide attacks that killed more than 250 people last month. How could a small group have planned such a devastating wave of bombings undetected?

The clues were there in mid-January, when Sri Lankan police stumbled upon 100kg (220lb) of explosives and 100 detonators, hidden in a coconut grove near the Wilpattu national park, which is a remote wilderness in Puttalam district on the west coast of the country.

Police were investigating attacks on statues of the Buddha by suspected Islamist radicals elsewhere in the country. Four men from a newly formed "radical Muslim group" were arrested.

Three months later, suspected Islamists blew themselves up in packed churches and hotels in Colombo, Negombo and the eastern city of Batticaloa killing more than 250 people, including 40 foreigners.

But that arms seizure in the coconut grove was not an isolated incident. It was just one of several suspicious incidents in the months leading up to the bombings that should have rung alarm bells, especially given reports that several Sri Lankans who had joined the Islamic State group in Syria were back home.

It didn't.

We now know the carnage on Easter Sunday happened despite repeated warnings about potential attacks from intelligence services in neighbouring India and the US.

It was only after the bombing that police identified links between two of those arrested in Puttalam in January and the suspected ringleader of the mass-casualty attacks.

Family circles

Political in-fighting and factionalism going all the way to the top of the Sri Lankan government is part of the reason warnings went unheeded, but complacency about the peace in Sri Lanka since the end of the civil war in 2009 also played a role.

Sporadic anti-Muslim riots since the end of the war between Tamil minority separatists and the government had fomented anger and discontent, but on the face of it nothing had pointed to a co-ordinated assault of this magnitude.

"The Islamists surprised everyone with the deadly bombings and at the same time kept the entire operation a secret," said a former Sri Lankan counter-terrorism operative who had been keeping a tab on some of the radicals involved in the Easter Sunday attacks.

It would have required detailed planning, safe houses, an extensive network of planners and handlers, expertise on bomb-making and significant funding - so how did all of this slip so far under the radar?

Few of these questions have been answered, but sources linked to security agencies, government officials and local Muslim leaders have painted a picture of how, over the years, a small number of die-hard radicals and IS sympathisers clandestinely set up cells right under the noses of the security forces.

Investigators say that certain members of individual families became radicalised and operated as units.

"That's how they kept their intentions and movements among themselves," said the counter-terror agent, who requested anonymity to speak openly, given the sensitivity of ongoing investigations.

Each unit then liaised with other radicalised family groups, forming larger networks. The supposition goes that information was tightly protected within networks of loyalty that transcended ideology. Encrypted social media networks and messaging apps are believed to have facilitated communication and planning.

"The investigators are now trying to find out how these people communicated and co-ordinated," the agent added.

"Using families to achieve their aim seems to be part of a new trend among these radicals. We have seen how some families were involved in suicide attacks [on a church and a police building] in Indonesia last year," said the former agent.

So far more than 70 people believed to be linked to the radicals have been arrested. But not everyone is convinced the networks have been dismantled.

"The main people involved in the attacks and those who made these bombs are still at large… So there are suggestions that there may be a second wave of attacks," a senior government official who did not wish to be identified told me last week.

"According to the theory of conventional terrorism, every suicide bomber needs at least five handlers. If you go by that there are 45 guys [for nine bombers] still out there. We are concerned."

It's a narrative at odds with what Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe has been saying. He recently declared that all suspects connected with the bombings had either been apprehended or killed.

At least 253 people were killed and about 500 injured in the attacks

The bombings have now put the spotlight on Muslims - the third biggest community in Sri Lanka, after the majority Sinhalese and Tamils. Muslims constitute around 10% of the country's population of 22 million.

During the civil war, Muslims suffered at the hands of the Tamil Tiger rebels. About 75,000 Muslims were expelled from the north by the rebels in 1990. Around 150 people were killed in attacks on mosques in the east the same year.

Later on, hundreds of Muslims joined the Sri Lankan security forces. They were particularly sought after by intelligence agencies as most Muslims are fluent both in Sinhala and Tamil languages. But while the Sri Lankan government was tied up fighting the Tamil ethnic insurgency, an ultra-conservative Islamic movement was quietly establishing a foothold in the Muslim-dominated areas of the east.

Muslims make up about 10% of Sri Lanka's population and only small numbers are believed to have become radicalised

"The process began nearly three decades ago. The Wahhabi brand of Islam attracted the young and it also had financial backing from abroad," said Mazook Ahamed Lebbe, an official from the Federation of Mosques in the eastern town of Kattankudy.

The beachside town, which has a population of around 47,000, is almost exclusively Muslim. A few shops in the centre of town sell the Abaya - a full-length black robe worn by some Muslim women. The town is dotted with colourful domes and minarets.

Kattankudy has around 60 mosques and more are being constructed. Muslim community leaders say that while most mosques adhere to moderate and mainstream teachings, some preach an ultra-conservative version of Islam.

Kattankudy's Muslims fear reprisals because the preacher came from their town

One of those attracted by the fundamentalist brand was Mohammed Zahran Hashim, a radical preacher from Kattankudy who, the government says, blew himself up at the Shangri-La Hotel on Easter Sunday.

Hashim's father sent him to a religious school for his education. But he soon started questioning the teachers, saying they were not following "true Islam". He was kicked out of the madrassa but continued his religious studies on his own and later started preaching - challenging the established practices of local mosques.

"We disagreed with his views. So we didn't allow him to preach in any of our mosques. Then he started his own group," said Mr Lebbe.

Hashim initially set up a conservative group called "Darul Athar" and later founded the hard-line National Thowheed Jamath (NTJ) around 2014. This is the group that has been blamed by the Sri Lankan government for the attacks.

Zahran Hashim has been identified as the ringleader of the bombers

Members of the NTJ had previously been known to police for vandalising Buddhist statues and clashing with other Muslim groups. The idea that they had the capacity to carry out the carnage of Easter Sunday left many perplexed.

In its early years, the NTJ managed to secure donations from overseas, particularly from the Middle East, India and Malaysia. The money helped the group to build its own mosque close to the beach in Kattankudy. The building has been sealed since the government banned the NTJ in the aftermath of the attacks.

The NTJ mosque Zahran Hashim founded once had hundreds of followers - but has now been shut

As a preacher, Hashim drew inspiration from the Wahhabi tradition, whose followers practise a strict and austere form of Islam.

But Muslim groups in Kattankudy say he went further and embraced an extremist ideology. The NTJ campaigned against the town's small community of Sufi Muslims, who follow a mystical form of the faith.

In 2017 Hashim and NTJ members clashed with a group of Sufi Muslims at an event, with his followers brandishing swords.

Ten members of the NTJ including the father and the second brother of Hashim were arrested. But Hashim and his brother Rilwan went into hiding. After widespread criticism, the NTJ said it had expelled him, but some Muslim leaders say Hashim remained influential in the group

While in hiding, he started releasing hate speech videos on social media in which he railed against "non-believers". It appears as if Hashim managed to draw most of his family members into his extremist way of thinking and convinced them to pursue the path of violence.

"They were a normal Muslim family. Hashim's father came from a poor background and was known to the community here. Hashim was a good preacher and well versed in the Koran... No one imagined that Hashim and his family could do such things," said Mr Lebbe.

"I met Zahran's father and one of his brothers a week before the Easter Sunday attacks. But they behaved in a normal manner. It is still a mystery to us how they got radicalised to this extent," a relative of Hashim and former NTJ member said.

Zahran Hashim's parents, two brothers and their families are believed to have been killed when they were cornered by security forces in Sainthamaruthu town, south of Kattankudy, on 26 April, just days after the attacks. Three men set off explosives, with 15 people in total killed, including several children.

Amid the wreckage, police found white dresses usually worn by Buddhist women during prayers at temples. They suspect that the militants had planned to enter temples in disguise during the Buddhist festival of Vesak in mid-May to carry out further attacks.

"We were able to account for five of the nine sets of dresses bought from a clothing shop. Four sets are missing," an officer at the site told me. Hashim's wife and daughter survived with injuries.

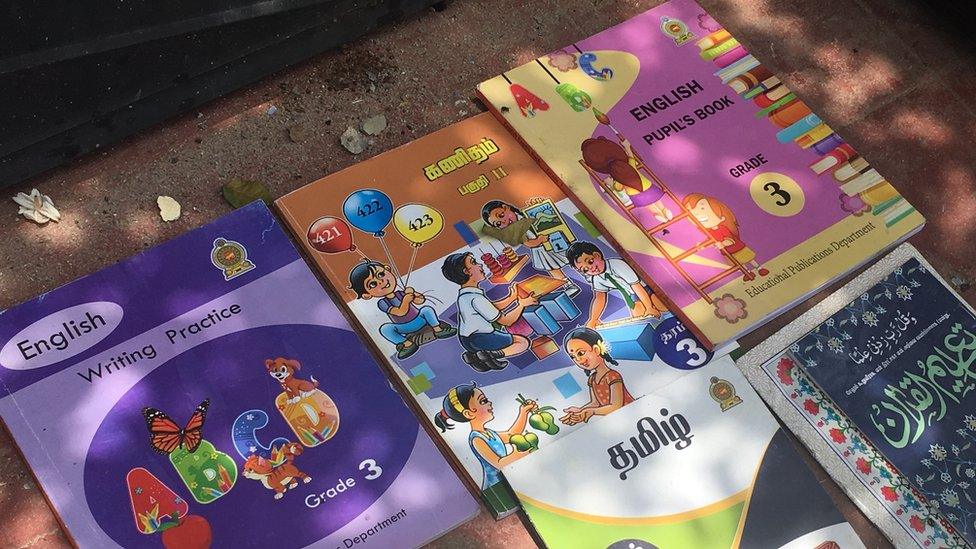

Children's schoolbooks were found amid the wreckage in Sainthamaruthu

On 24 April, Mohammad Hashim Madaniya, the sister of Hashim, told the BBC she strongly condemned her brother's actions and said she had lost contact with him two years ago. She said she had not seen or heard anything from her extended family since shortly before the blasts. By her version of events, she was one of few members of the family who was not part of the network.

A week later, police arrested Ms Madaniya, saying they had found nearly two million Sri Lankan rupees ($12,000) from her house during a raid. They alleged that she had received the money from her brother in Colombo a few days before the blasts. There has been no response from Ms Madaniya, who remains in custody.

Radicalisation

Some have wondered if anti-Muslim riots in the central district of Kandy in February 2018 might have pushed more people towards extremism.

At least two people were killed, a mosque was set on fire and hundreds of houses and shops were damaged by mobs in violence that led to a state of emergency being imposed. Local Muslims told me in the aftermath that they felt the state did not do enough to protect them.

But very small numbers of Muslim youth had become radicalised years before those riots. Authorities say dozens were drawn towards IS after the extremist group declared a caliphate in Syria and Iraq in 2014.

Anti-Muslim riots in Kandy last year led to a state of emergency being imposed

A school principal from central Sri Lanka, Mohamed Muhsin Nilam, was the first Sri Lankan to join IS in Syria. He died in Raqqa in 2015. "It is believed that he was the one who influenced or played a major role in radicalising some of the suicide bombers who attacked on Easter Sunday," said the counter-terrorism agent.

It's not clear whether any of the bombers actually travelled to Syria. Investigators say Abdul Latheef Mohamed Jameel made it as far as Turkey in 2014 but then returned home.

Jameel, who hailed from a wealthy family involved in the tea trade, studied in the UK and Australia before he tried to go to Syria. His target on 21 April was the luxury Taj Samudra hotel in Colombo but his bomb probably failed and he was seen leaving the premises. He later blew himself up at a motel in the suburb of Dehiwala, killing two guests.

A man believed to be Abdul Latheef Mohamed Jameel seen leaving the Taj Samudra Hotel

Investigators suspect that Jameel, a 37-year-old with four children, was the link between local radicals and IS or other Islamist groups based abroad.

Several years ago, his family became concerned about his hardline views and enlisted the help of a security official.

"He was completely radicalised and supported the extremist ideology. I tried to reason with him," the official said. "When I asked him how he got into this… he said that he attended the sermons of the radical British preacher Anjem Choudary in London. He said he met him during the sermons."

Anjem Choudary is considered one of the UK's most influential and dangerous radical preachers. He was convicted and jailed in 2016 for inviting support for the Islamic State group but was released in 2018.

Friends of Jameel have said that the US invasion of Iraq was a major factor in shaping his hardline views. Investigators believe he became more radicalised after moving to Australia in 2009. When he returned to Sri Lanka four years later he was placed under surveillance, though it's unclear how long this lasted.

The spice traders

It is not completely clear how Hashim, a cleric from the east, established contact with two sons of a well-known wealthy spice trader in Colombo - Inshaf Ahmed Ibrahim and Ilham Ibrahim. The brothers both carried out suicide attacks on Easter Sunday.

One Muslim community leader told me that Hashim had married a woman from the central town of Kurunegala. Ilham Ibrahim, who targeted the Shangri-La with Zahran Hashim, managed the family's spice farm in Matale, about 50km away from Kurunegala. It is suspected that Ilham Ibrahim and Hashim came into contact in that area.

Hours after the first blasts, police raided Ilham Ibrahim's family villa in the Dematagoda suburb of Colombo. Police say his wife, Fatima Ibrahim, detonated a suicide vest, killing herself, three of their children and three officers.

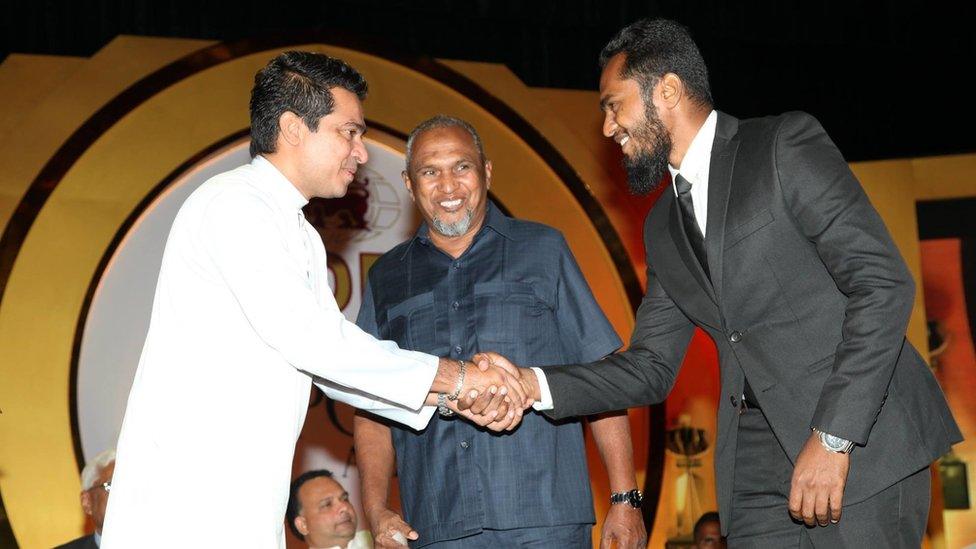

Inshaf Ibrahim (R) and his father (C) accepted an award in 2016 from a Sri Lankan minister

Officials and security experts are clear that staging nine suicide operations would have required careful planning and huge financial support.

Two other suspects, Mohammad Abdul-Haq and Mohammad Shaheed Abdul-Haq, who hail from the central town of Mawanella, were arrested a week after the bombings. They are suspected of having had links to the Ibrahim brothers.

"Investigators have found a safe house of the Haq brothers in Puttalam district overlooking a lagoon. Investigators have found links suggesting that the advance money to buy the property came from one of the Ibrahim brothers," said the former intelligence operative.

The father of the Ibrahim brothers, Mohamed Ibrahim, remains in custody. He is well-known among Colombo business circles, politically well-connected and once unsuccessfully ran for parliament. He has not been charged and has not been heard from since he was detained.

Investigators believe that Jameel influenced the Ibrahim brothers. The families knew each other.

The political factions

While Sri Lankans are still reeling from the shock and pain of the attacks, they are also equally appalled by the political bickering and official handling of the aftermath of the blasts.

President Maithripala Sirisena and Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe belong to two different political parties and have a hostile relationship. Their efforts to undermine each other appear to have created a communications gap at the heart of the government.

President Maithripala Sirisena (L) and Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe (R) are at loggerheads

The president oversees the security forces and soon after the bombings, the prime minister said that an Indian intelligence warning about attacks had not been shared with him. President Sirisena has made a point of saying that top intelligence officers did not share the information with him either.

Bhavani Fonseka, a human rights lawyer, said bickering between the two leaders was affecting the country. "It is more to the point of how it has impacted the security…That's a deeply troubling point," she said.

The lack of communication between various arms of the government was also laid bare when two ministries blamed each other for providing wrong casualty figures. The number of dead in the bombings was lowered five days after the attacks by more than a hundred.

At one point, Sri Lankan police had to apologise after wrongly identifying a US woman as a suspect.

Sri Lanka president: IS 'chose Sri Lanka to show they exist'

Most government officials who spoke to the BBC admit that sleeper cells are likely still out there.

But that raises the question of why the Islamic State group is targeting a country like Sri Lanka, where Muslims are a minority.

The senior government official said the group - now physically decimated in Syria and Iraq - sees the island as "part of their caliphate".

President Sirisena, meanwhile, told the BBC earlier this week that they had chosen a "country that recently established peace to make the statement that IS still exists".

Sri Lanka is a war-scarred society and suffered extreme violence for decades. But this time, the forces it is trying to confront are invisible and drawing inspiration, and possibly support from global terror networks. The battle is likely to be long and drawn out and many fear that as long as politics remain fractured, the country will be vulnerable.

- Published28 April 2019

- Published28 April 2019

- Published28 April 2019

- Published26 April 2019