South Korea pollution: Is China the cause of 'fine dust'?

- Published

Hwang Mi-sun used to watch over her baby son as he slept at their home in Seoul, to listen to every laboured breath.

From a young age he suffered from respiratory problems.

He's now four years old and has been given various drugs including strong steroid treatment to try to help. But after his fourth trip to hospital, the doctor had another piece of advice.

Mrs Hwang was told to keep her young son inside to save him from South Korea's toxic air.

"It was sad that my child started to learn not just words like mum and dad, but also fine dust so early on," she told me. "I even thought moving out of the country but I really want to live in Korea. So I'm going to do whatever I can help to solve the problem."

Hwang Mi-sun's baby has struggled with breathing problems his whole life

She decided to start campaigning and joined a group called Mothers Against Fine Dust, which stages protests and lobbies the government about the pollution.

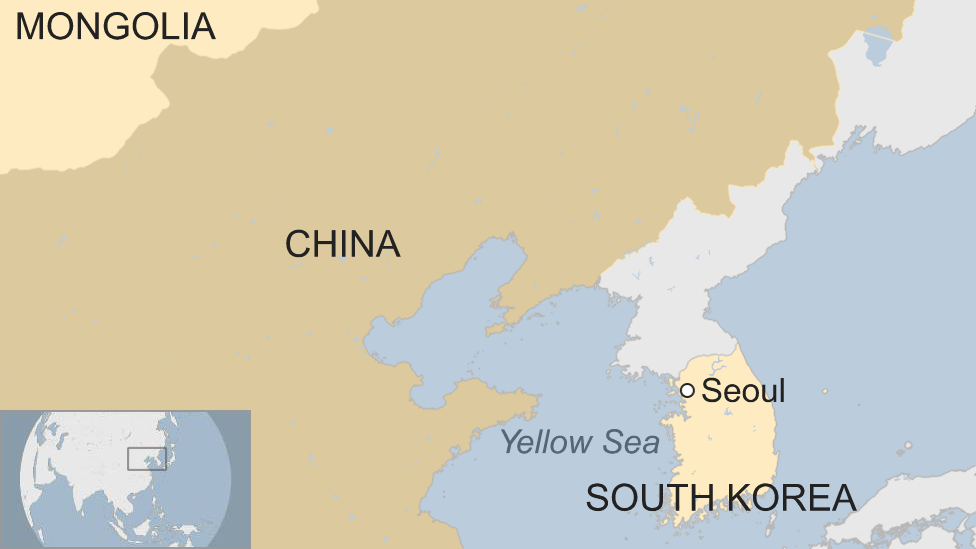

The "fine dust" they're concerned about refers to sand which is picked up from Mongolian and Chinese deserts on prevailing winds during certain times of the year and blown to the peninsula.

But the almost romantic description hides the reality facing Koreans.

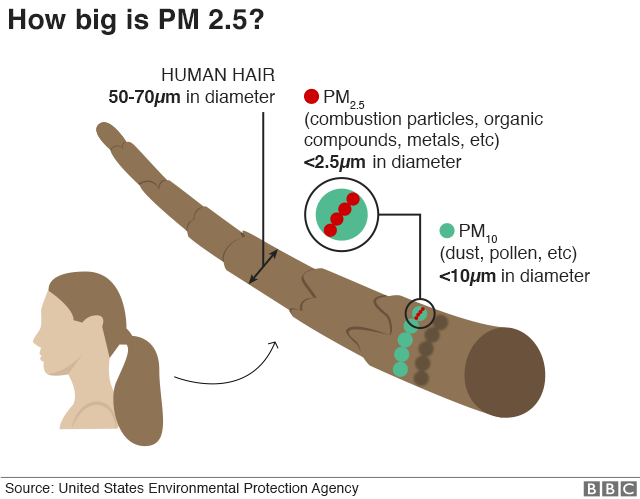

This air also contains carcinogens, invisible nano particles known as PM2.5 which can penetrate deep into the respiratory system and trigger a variety of illnesses including cancer. The lungs of children and the elderly are particularly susceptible.

'Violates our basic right to breathe'

Earlier this year, the levels of microfine dust particles PM 2.5 was recorded at 118 micrograms per cubic metre, the highest since monitoring began in 2015, according to the National Institute of Environmental Research.

Mrs Hwang moved her family out of Seoul to the suburbs to try to save her son from breathing in the worst of the "fine dust". But still she wanted to do more. Her campaign group was allowed to give evidence to politicians at the National Assembly.

The public hearing was fraught with emotion as mother after mother detailed the effects the pollution was having on their family. Many brought their toddlers who sat on their laps wearing face masks.

"Air pollution violates our basic right to breathe. I don't think it is a country if we don't even have the right to breathe," said one.

"Children just want to go outside and play. Nothing special, just to enjoy the change of seasons. To think that we are taking that away from them is heartbreaking," said another.

The pollution can trigger a variety of illnesses including cancer

South Koreans are growing increasingly concerned about the effects the pollution is having on their health - 97% of people asked by the ministry of environment last year said air pollution was causing them physical or psychological pain.

The government's response has been to declare the "fine dust' as a social disaster to release emergency funding.

Asia's fourth largest economy has spent billions over several decades to defend itself against the threat of war from its North Korean neighbour - now it has to turn its attention to the effects the air is having on its population.

But is this new enemy from within or without?

Experts can't agree. Some say the polluted air comes from China - studies have suggested that as much as 60% of South Korea's air pollution comes from its western neighbour's industrial sites and coal plants.

Others say the problem lies closer to home.

Dangerous pollutants on the wind

To try to find out, officials from the environment ministry have been taking to the skies over the Yellow Sea, between the Korean peninsula and China.

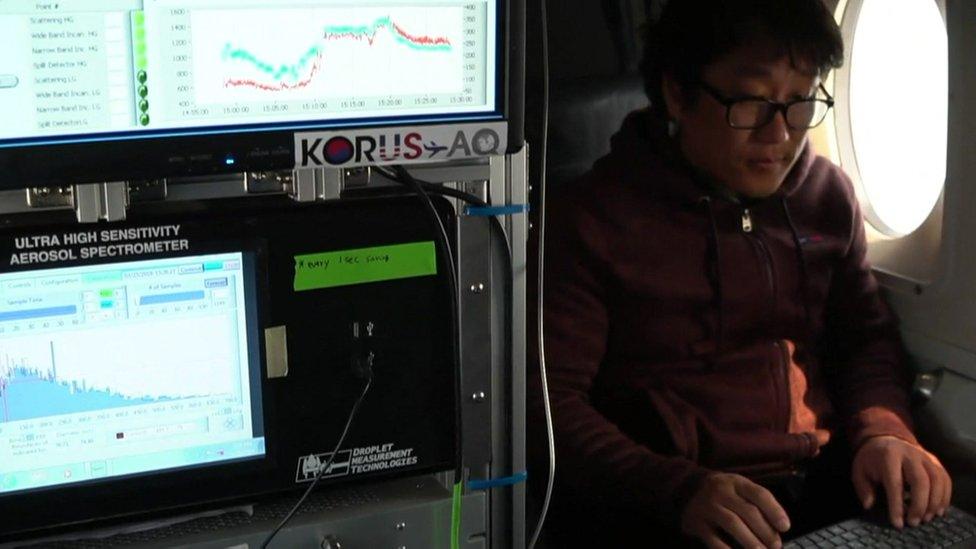

Researcher are looking into the content and origin of the "fine dust"

We were allowed to go with them. It is incredibly cramped inside the specially adapted aeroplane, but they managed to give me a brief tour. We had to squeeze into tiny spaces between the various computers and numerous measuring devices.

Above a revving engine, the head researcher tells me the idea is to take samples of the air as we fly over the peninsula and measure them for various carcinogens and pollutants.

From the air the thick pollution can be seen hanging over South Korea

The instruments can tell which kind of particles come from certain industries such as coal power plants and which dangerous pollutants are carried by the wind. It will help give the scientists clues as to whether the bad air originated in China or South Korea.

As we climb above the peninsula, we soar near some of South Korea's own power plants. Coal generates about 40% of the country's total electricity, followed by nuclear and gas. Last year, South Korean coal imports hit a record high.

The government has closed down a number of ageing plants, but there are plans to build new ones in the next five years which has angered those campaigning for cleaner air.

Before we took flight I'd spoken to to Lee Ji-eon from the non-profit organisation, the Korean Federation for Environmental Movements (KFEM).

"All plans to build new coal plants should be halted," he said. "We also need to come up with a roadmap to reduce the share of coal-fired power generated electricity to below 20% by 2030. "

The government hasn't quite gone that far, but it has unveiled a new energy master plan to increase the amount of renewable energy it generates to 20% by 2030.

A political issue

Back on board, and after an hour flying over the Yellow Sea, there is no longer a view outside my window. The air is not just hazy, it is so thick only shreds of light make their way through. We are about 500m above sea level and the scientists are busy recording various readings of sulphur dioxide and what was described to me as black carbon.

The head researcher Ahn Joon-young is pointing out some of his findings. It seems the closer we get to China, the more polluted the air is becoming. On this day at least.

"My research goal is: where does this pollution come from, how much is it coming to Korea, and what is it we have to collaborate with other countries [on] to reduce our air pollution," he tells me.

"I am finding higher concentrations of black carbon and sulphur dioxide over the sea than we found inland. That means that some pollutants have travelled from another region to Korea."

When I ask him where they may have travelled from he laughs a little nervously.

"It is a political issue, I hear," he says.

Too little, too late?

He may not want to name China on camera, but other South Korean officials have been far more forthright.

The mayor of Seoul, Park Won-soon, said earlier this year that environmental researchers had concluded that China was responsible for 50-60% of South Korea's pollution problem.

China has stated on a number of occasions that it is not entirely to blame for South Korea's air quality and has urged Seoul to take more responsibility.

Children and the elderly are most at risk

Lee Ji-eon from KFEM agrees. "Pointing the finger of blame at others will never solve the problem - especially as there are things we can do.

"If we are asking China to take action, it would make a more convincing argument if we have dealt with our own problems first. For instance, we clearly know diesel cars contribute the most to urban fine dust and yet the total number of diesel cars has increased which is the clear indication of policy failure."

South Korea's President Moon Jae-in has appointed the former United Nations Secretary General Ban Ki-moon as a fine dust tsar.

Parents say they want their children to live normal lives and play outdoors

He stressed the need to identify the source of the dust first before drafting further policies and we await the findings from a month of flights over the Yellow Sea.

Environmentalists have welcomed this appointment, and the research, but they believe that is still too little and already it is too late for those suffering serious health problems.

Every year, 18,000 people are thought to die from pollution related illnesses in South Korea, according to the World Health Organization.

The issue also seems to drift in and out of newspaper headlines and the public consciousness along with the seasons. Politicians come under pressure to solve the problem only when the fine dust is at its worst during spring and winter.

But people such as Hwang Mi-Sun are always aware that their families are at risk. She believes drastic action is needed now if South Korea is to save the health of its next generation.

"I don't ask for much. I just want my children to run outside under a blue sky and play with the soil on the ground. That's my biggest wish."

- Published26 April 2019

- Published18 November 2018

- Published2 April 2019

- Published30 April 2019

- Published28 August 2018

- Published15 May 2019