Pakistani children worst affected in HIV outbreak

- Published

At least one doctor has been arrested in Pakistan over the outbreak, which has disproportionately affected children

The first sign that something was wrong in the small southern Pakistani town of Ratto Dero appeared in February.

A handful of worried parents had taken their children to the doctor, complaining that their little ones could not shake off a fever.

Within weeks, more children came forward suffering from a similar illness.

Bemused, Dr Imran Aarbani sent the children's blood away for testing. What came back confirmed his worst fears. The children were infected with HIV - and no-one knows why.

"By 24 April, 15 children had tested positive, though none of their parents were found to be carrying the virus," the hospital doctor told the BBC.

It was only the tip of the iceberg.

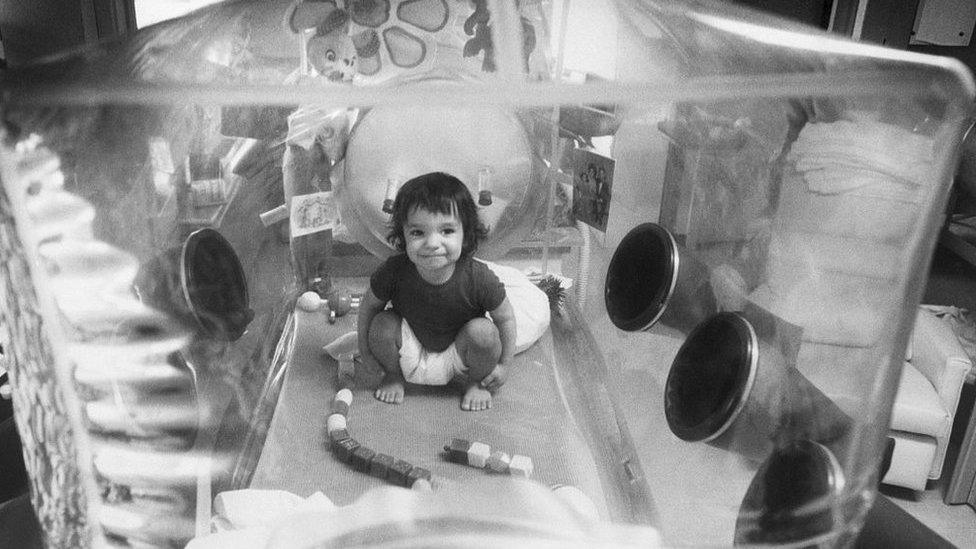

In the past month, more than 607 people - 75% of them children - have been diagnosed with the virus after rumours of an outbreak sent families rushing to a special camp set up at the town's government hospital by the health department of Sindh province.

Perhaps more surprising, however, is the fact that this is not the first outbreak to hit the region in recent years.

Thousands of people are being tested around the country

Rumours of a possible outbreak in Sindh province's Larkana, of which Ratto Dero is a sub-division, prompted thousands of people to get tested back in 2016.

On that occasion, 1,521 people were found to be HIV positive, according to figures available with Sindh Aids Control Programme (SACP).

The vast majority of those infected were men and, at the time, the cause was linked to the area's sex workers, who were mainly transgender and 32 of whom were found to be carrying the Aids virus.

The discovery of the outbreak led to a crackdown on Larkana's travellers' inns, where sex workers had been able to ply their trade relatively freely, despite a ban on prostitution in Pakistan.

But could that outbreak be linked to health officials' recent discovery?

Read more like this

Dr Asad Memon, who heads the SACP operations in Larkana, believes so - although not directly.

"I think the (Aids) virus was being carried by members of the high-risk group (transgender and female sex workers) and then lax practices by local quacks caused it to infect other patients," he told the BBC.

By "quack" he is referring to under-qualified people practising medicine, ranging from paramedics running a private clinic posing as doctors, to medical graduates who have been unable to find work in hospitals and have no exposure to standard medical practices.

Multiple use of single syringes is suspected to be a factor in the new outbreak, though investigations are ongoing

In Pakistan, especially in rural areas, people often go to "quacks" instead of qualified doctors because they are cheaper, easily available, and have more time to give to their patients.

Dr Fatima Mir, who works for the Aga Khan University Hospital and specialises in Aids among children, is currently doing volunteer work in Ratto Dero. She agrees that negligent medical practices are the most likely link between the children and the 2016 outbreak.

"There are three ways a child may be infected," she explained. "It's either through a lactating mother who carries the virus, through blood transfusion, or through an infected surgical instrument or a syringe."

In most cases she has handled, the mothers tested negative for HIV and few children had undergone blood transfusions. So the only remaining explanation was the practice of using one syringe for several patients at local clinics.

Officials also appear to agree. About 500 unregulated clinics have been ordered closed across the province, the health authorities reported.

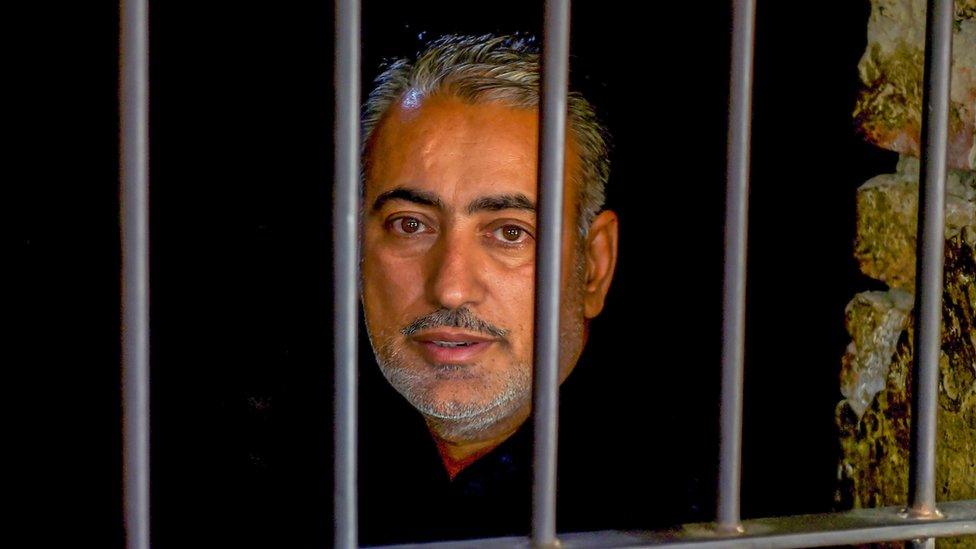

What's more, a local child specialist, Dr Muzaffar Ghangro, has been arrested on charges of spreading Aids through syringes.

He has denied the charge, saying all the infected people were not his patients.

Dr Muzaffar Ghangro was arrested on suspicion of spreading Aids by re-using syringes at his clinic - a claim he denies

Meanwhile, officials in Sindh - which has one of the highest HIV infection rates in Pakistan - have set up an inquiry to identify causes of the outbreak.

But that will not help those who have already found themselves with a diagnosis that will impact on their whole lives.

Doctors at the hospital camp in Ratto Dero have now tested more than 18,418 people since 25 April.

At least 607 of them have tested positive so far, three-quarters of them children between the ages of one month and 15 years.

That means there are hundreds of parents left counting the cost - both to their children's health, and their everyday existence.

"Medicines for grown-ups are usually available [with health authorities] in Larkana, but for the child's medicines we have to go to Karachi, which means we spend several thousand rupees on each trip," one mother, whose three-year-old daughter had been diagnosed as HIV-positive, told the BBC.

"My husband is only a day-labourer, so we won't be able to afford this for long."

- Published3 May 2019

- Published17 April 2019

- Published29 March 2019

- Published5 March 2019