Mount Everest: Why the summit can get so crowded

- Published

Nepal issued 381 permits at $11,000 each for this spring's climbing season

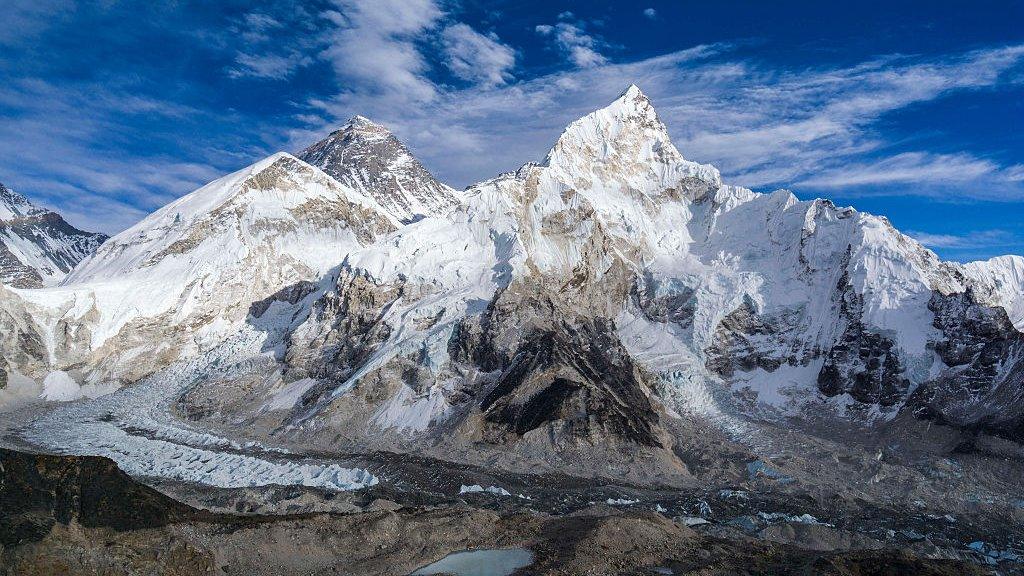

If you imagine the summit of Mount Everest, you might picture a quiet, snowy peak far from civilisation.

But a striking photo, taken by mountaineer Nirmal Purja, shows how the reality can be a lot more crowded.

Mr Purja's photo, external has attracted attention around the world - amid the tragic news that seven climbers died on Everest in the past week.

The picture gives a glimpse into the tough conditions facing climbers at the highest peak in the world.

Is it normal to see such long queues near the summit?

Yes - according to guides, this happens quite often during the climbing season.

"It's normally that crowded," says Mingma Sherpa, chairman of Seven Summits Treks, adding that climbers sometimes queue between 20 minutes, and 1.5 hours, in order to reach the summit.

It often depends on how long the window for suitable climbing weather is - because mountaineers need to avoid fierce jet streams that would hinder them.

"If there's one week [of safe weather], then the summit isn't crowded. But sometimes, when there's only a window of two or three days, it gets very crowded" as all the climbers try to reach the summit at the same time, Mingma Sherpa tells the BBC.

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

It's not the first time crowds at Everest have made headlines either.

In 2012, another photo, taken by German climber Ralf Dujmovits, external, went viral, as it showed what he called a "conga line" of mountaineers at Everest.

Is overcrowding dangerous?

Mr Dujmovits, who reached the Everest Summit in 1992, and ascended 8,000m (26,200 ft) up the mountain on six other occasions, says that long queues at the summit can be hazardous.

"When people have to wait in queues, they risk running short of oxygen - and may not have enough oxygen left on their way down."

During his 1992 climb, he ran out of oxygen during his descent, and felt as though "someone was hitting me with a wooden sledgehammer", he says.

"I felt I almost couldn't make any progress - I was pretty lucky I could recover enough and eventually make my way down safely."

"When you have winds of stronger than 15km/h (9mph), you just can't make it without oxygen... you're losing so much body warmth."

To make matters worse - sometimes, oxygen cylinders left out for designated climbers get stolen.

"Stealing oxygen at such altitude is no less than killing somebody," Maya Sherpa, who reached the summit three times, told BBC Nepali. "The government needs to co-ordinate with the Sherpas to enforce rules."

Why are there 'traffic jams'?

Experts say crowds at Everest have also increased in recent years because expeditions have become more popular.

Andrea Ursina Zimmerman, an expedition guide who reached Everest's peak in 2016, says that many "traffic jams" are caused by unprepared climbers who "do not have the physical condition" for the journey.

This risks not only their lives, but the lives of the Sherpas taking them up the mountain.

Andrea Ursina Zimmerman and Norbu Sherpa celebrating on their way back to base camp

Ms Zimmerman's husband, mountain guide Norbu Sherpa, recalls having an argument at 8,600m with a climber who was exhausted but insisted he wanted to continue to the summit.

"We had a big argument, and I had to tell him he was risking the life of two Sherpas as well as his own, before he would come down. He couldn't even walk properly - we had to slide him down with ropes - so by the time we reached base camp he was really grateful."

What's it like reaching a crowded summit?

Norbu Sherpa has reached the summit seven times. He says it is much more crowded from the Nepali side - the Tibet side is easier, but the Chinese government issues fewer permits, and the climb is less interesting.

At the last ridge from the southern, Nepali side, there is only one fixed rope.

When it's crowded, "there can be two lines of people - one going up, and one going down the summit," he says, adding: "Everyone is hanging onto this one rope".

He adds that the most dangerous part is often the descent.

A lot of people push themselves to the summit, but, once they reach it, "lose their motivation and energy on the way down", especially when they realise it's a long, crowded journey.

Is it worth reaching the summit?

Mr Dujmovits says that, despite being exhausted, he felt "a total release" when he got to the top.

However, descending safely - even if you haven't reached the summit - is much more important, he says.

"I lost so many friends who died during the descent over the years - many accidents happen during the descent because people are just not concentrating enough anymore - especially in the case of Everest where there are big crowds going up and down."

"The real summit is actually back at base camp - when you're back, you can really feel the enjoyment of everything you've done."

Many expedition guides stress that reaching the top is immensely rewarding - but being physically prepared, and choosing the right time to ascend, go a long way towards reducing the risk.

Andrea Ursina Zimmerman on her descent from the Everest summit

Practising climbing mountains at 7,000m or 8,000m is essential so people know "how their bodies react to those altitudes", says Norbu Sherpa.

He also encourages his teams to start the ascent "very early" in the day, so they can descend before other climbers start coming up.

Ms Zimmerman ascended Everest from the Tibet side, but deliberately chose to wait an extra day before ascending the summit so it would be less crowded.

She was aware that there was a risk the weather window would close and her expedition would end without her reaching the top - but says it was worth it because she and her husband ended up "alone on the summit".

"I cannot even describe how it feels to be with your husband, alone at the top of the world... We arrived at 03:45, waited, and saw the sunrise."

- Published21 March 2019

- Published18 April 2018