Japan whaling: Why commercial hunts have resumed despite outcry

- Published

Japan has resumed catching whales for profit, in defiance of international criticism.

Its last commercial hunt was in 1986, but Japan has never really stopped whaling - it has been conducting instead what it says are research missions which catch hundreds of whales annually.

Now the country has withdrawn from the International Whaling Commission (IWC), which banned hunting. It sent out its first whaling fleet on 1 July, with permits to catch 227 whales.

The first whale - a minke - was brought back to shore that day.

Isn't whaling banned?

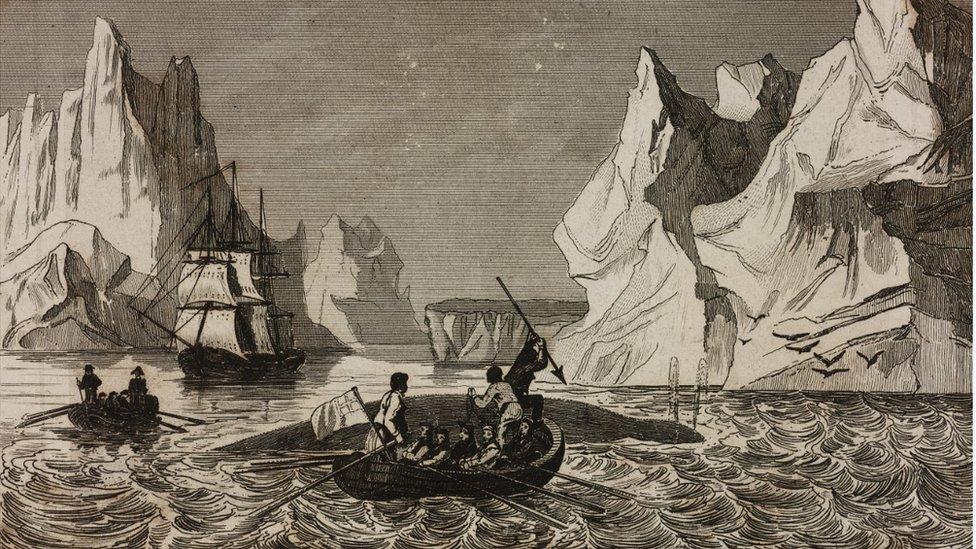

Whales were brought to the brink of extinction by hunting in the 19th and early 20th Century. By the 1960s, more efficient catch methods and giant factory ships made it obvious that whale hunting could not go unchecked.

So in 1986, all IWC members agreed to a hunting moratorium to allow whale numbers to recover.

Conservationists were happy but whaling countries - like Japan, Norway and Iceland - assumed the moratorium would be temporary until everyone could agree on sustainable quotas. Instead it became a quasi-permanent ban.

There is a long history to anti-whaling protests

But there were exceptions in the moratorium, allowing indigenous groups to carry out subsistence whaling, and allowing whaling for scientific purposes.

Tokyo put that latter clause to full use. Since 1987, Japan has killed between 200 and 1,200 whales, external each year, saying this was to monitor stocks to establish sustainable quotas.

Critics say this was just a cover so Japan could hunt whales for food, as the meat from the whales killed for research usually did end up for sale.

Why is Japan restarting whaling now?

In 2018 Japan tried one last time to convince the IWC to allow whaling under sustainable quotas, but failed. So it left the body, effective July 2019.

Whaling is a small industry in Japan, employing around 300 people. About five vessels are expected to set sail in July.

The whaling "will be conducted within Japan's territorial waters and Exclusive Economic Zone", Hideki Moronuki of the Japanese fishing ministry told the BBC in June.

Japan catches first whales after ban lifted

This means Japan will no longer hunt whales in the Antarctic, as it did under its earlier research programme.

The catch cap of 52 minke whales, 150 Bryde's whales and 25 sei whales is also lower than the 333 cap set for last year's research hunt.

Like other whaling nations, Japan argues hunting and eating whales are part of its culture. A number of coastal communities in Japan have indeed hunted whales for centuries but consumption only became widespread after World War Two when other food was scarce.

From the late 1940s to the mid-1960s whale was the single biggest source of meat in Japan but since become a niche product again.

Is Japan's plan legal?

"Within its 12 mile coastal waters, Japan can do whatever it wants," Donald Rothwell, professor of international law at the Australian National University, told the BBC.

Beyond that, in its 200 miles (322km) exclusive economic zone and of course the high seas, the country is bound by the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea.

Article 65 of said convention, external mandates that "states shall co-operate with a view to the conservation" of whales and "shall in particular work through the appropriate international organizations for their conservation, management and study".

Traditional whaling often resulted in a drawn-out death for the animal

Having left the IWC, Japan is no longer part of any such international organisation and that "directly raises questions issues whether or not Japan would be consistent with the convention," Mr Rothwell explains.

It's not clear if any country would try to bring Japan to court over this - in its defence, Japan might argue that for years it did try to co-operate within the IWC without any results.

Even if there were to be a ruling or injunction against Tokyo, there'd be no mechanism to enforce it.

What environmental impact will Japan's whaling have?

The ministry will allow for the hunting of three species: minke, Bryde's and sei whales.

According to the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species, minke and Bryde's whale are not endangered. Sei whale are classified as endangered, external but their numbers are increasing.

So in terms of numbers, Japan's commercial whaling will have only a minimal impact.

In fact, some defenders of whaling argue that whale meat has a smaller carbon footprint than pork or beef.

Is eating whale meat more ethical than commercially farmed pork or chicken?

Conservationist groups like Greenpeace or Sea Shepherd remain critical of Japan's resumption of whaling but say there are no concrete plans yet to tackle the country over this.

Japan "is out of step with the international community", Sam Annesley, executive director at Greenpeace Japan, said in a statement, urging Tokyo to abandon its hunting plans.

Besides the question of stock sustainability, a key argument against the hunt is that harpooning whales leads to a slow and painful death.

Modern hunting methods, though, aim to kill whales instantly and it backers say the near-global anti-whaling sentiment is deeply hypocritical., compared to, say, industrial meat production.

But even if Japan does defy the criticism and stick with whaling, there's a good chance the contentious issue will gradually die down by itself.

Japanese demand for whale meat has long been on the decline and the industry is already being subsidised. Eventually, commercial whaling might be undone by simple arithmetic.

- Published20 June 2019

- Published26 December 2018

- Published12 September 2018

- Published7 September 2018

- Published30 May 2018