Gotabhaya Rajapaksa: Sri Lanka's controversial ex-defence chief eyes power

- Published

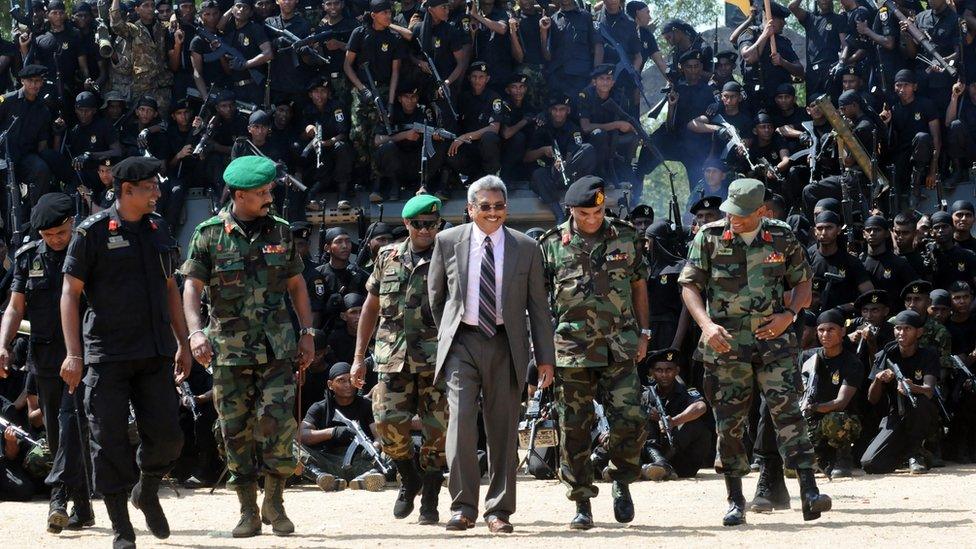

Sri Lanka's former defence secretary, Gotabhaya Rajapaksa (C), pictured in 2010

Sri Lanka's controversial former defence chief, who played a leading role in crushing Tamil rebels in a bloody civil war which ended 10 years ago, has been nominated as the opposition's presidential candidate in the forthcoming election.

Gotabhaya Rajapaksa is loathed by Sri Lanka's minority Tamils but celebrated as a hero by many in the majority Sinhalese population, particularly hardliners.

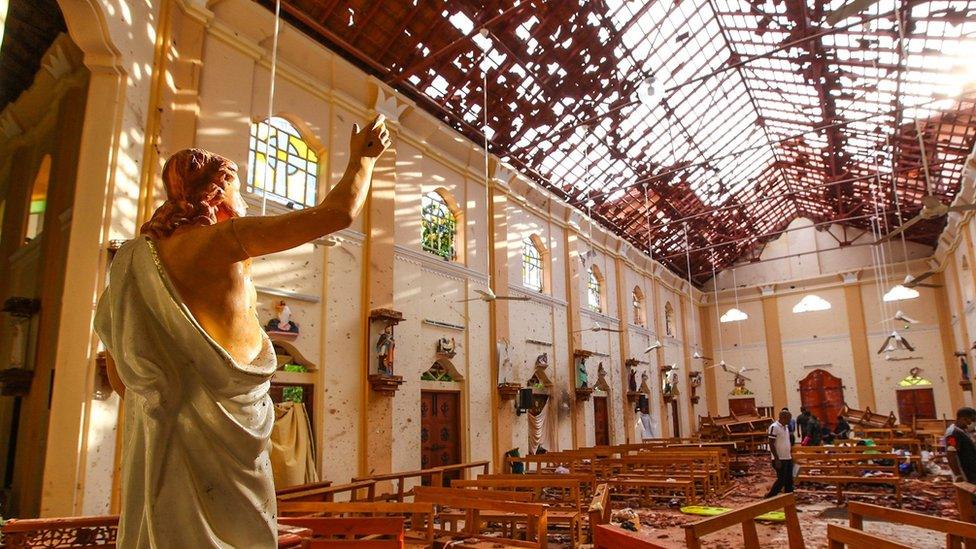

He believes he can capitalise on calls for a strongman to govern the country rocked by a series of suicide attacks by Islamists on Easter Sunday which left 253 people dead.

"I will accept responsibility for your safety, and the safety of your children and your loved ones," Mr Rajapaksa said at the conference of the Sri Lanka People's Front in Colombo on Sunday.

There is widespread anger against the present government for its perceived failure in preventing the attacks - and the governing alliance is yet to name its candidate for the election, which will be held before 9 December.

Mr Rajapaksa's nomination will disappoint minority Tamils and those who were victims of rights abuses when he headed the powerful defence ministry between 2005 and 2015. His brother Mahinda Rajapaksa led the country as president during this period and cannot run again because of Sri Lanka's two-term limit.

Several journalists who were critics of the previous government were abducted, tortured and killed when the Rajapaksas led Sri Lanka. Thousands of people, particularly Tamils, vanished in what has been described as enforced disappearances.

But in the immediate aftermath of the Easter Sunday bombings, feelings were raw. At a funeral for one of the victims, a grief-stricken relative wailed and shouted: "We need Gota, We need Gota."

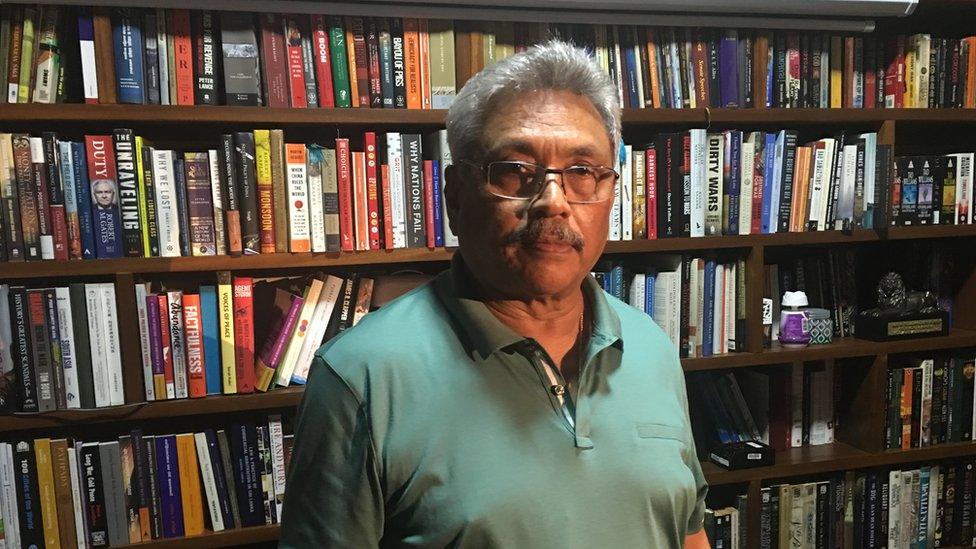

Mr Rajapaksa spoke to the BBC from his home in Colombo in the aftermath of the attacks. When asked about allegations against him, including war crimes, he dismissed them all as "baseless" - and vowed that he would be the one leader who could boost the nation's security.

"I think any country, any government or leaders must be first security conscious, especially this era when all over the world there are terrorist incidents are happening," he told me.

More than 250 people were killed in the Easter bombings

I first met Mr Rajapaksa 10 years ago in Colombo during the final stages of the civil war. He was known for his volatile temper, and many journalists were too scared to ask him tough questions, especially questions about alleged rights abuses committed by Sri Lankan security forces.

But during our most recent meeting, even before he was officially nominated as a candidate, Mr Rajapaksa sounded like a different man. Sitting in his study, surrounded by books, he answered difficult questions calmly.

He said he was confident of victory, but he had some hurdles to surmount. His candidacy was also in doubt for months as he held dual nationality. Although Mr Rajapaksa has said he has renounced his US citizenship, his opponents are still calling on him to provide evidence that he has done so.

There also remain serious concerns that under Mr Rajapaksa's presidency the rights of the religious and ethnic minorities will not be respected. In his speech on Sunday, Mr Rajapaksa tried to dispel such fears.

"I pledge to create a safe and secure environment in which all Sri Lankans, irrespective of their race or religion, will be able to live in peace," he said.

Gotabhaya Rajapaksa is running as a national security candidate

Another cloud hanging over Mr Rajapaksa relates to cases against him in US courts. In the first, filed in April, he is accused of ordering the murder of a newspaper editor, Lasantha Wickrematunge, in Sri Lanka a decade ago. A second case relates to the alleged torture of a Tamil detainee during the war.

Wickrematunge was the well-known editor of The Sunday Leader and a vocal critic of the Rajapaksas. He published a series of reports alleging corruption in arms deals by then-defence secretary Mr Rajapaksa.

Wickrematunge received death threats for his reports, and wrote an editorial before his death predicting that the government would kill him. In January 2009, he was shot and stabbed to death in broad daylight in Colombo by unidentified men. No-one has been brought to trial for his murder - and few expect anyone ever will be.

The murder shook the nation, coming just days before the editor was to give evidence against Mr Rajapaksa. Mr Wickrematunge's daughter, Ahimsa, is now seeking unspecified damages in the case filed in California. It accuses Mr Rajapaksa of instigating and authorising her father's murder.

Lasantha Wickrematunge edited the Sunday Leader, which was critical of then President Mahinda Rajapaksa

The second case relates to Roy Samathanam, a Tamil civilian with Canadian citizenship. He was arrested in Sri Lanka before the war ended over suspected links with the Tamil Tigers. He alleges he was tortured in custody and forced to sign a confession before he was released in 2010.

The cases were filed in US courts because of Mr Rajapaksa's American citizenship. "Both cases are baseless because I did not do these things," he told me. He listed various actions taken during his tenure to bring Mr Wickrematunge's killers to justice.

Since I interviewed him, the number of cases Mr Rajapaksa is facing has risen. On 26 June, 10 more plaintiffs filed papers in Californian courts seeking damages from him. They allege that they were tortured and, in some cases, raped and sexually assaulted by security forces under his command.

All the allegations against him are "politically motivated", Mr Rajapaksa said. "I have been visiting the US for so many years, Why [are they raising it] at this time?"

Even if he has indeed denounced citizenship, the cases could still proceed.

The Easter Sunday bombings happened just a month before the country observed the 10th anniversary of the end of the war with the Tamil Tigers. The conflict lasted almost three decades and it is estimated at least 100,000 people were killed. The UN and other agencies estimate that at least 40,000 people were killed in the last stages when the Sri Lankan military launched its final assault.

Tens of thousands of civilians, and the rebels themselves, were eventually trapped in a small sliver of coastal land in the north-east. The military pounded the area with artillery while the rebels also shot civilians trying to escape. A UN official in Colombo at the time said their warnings of a bloodbath had become a reality.

The Tamil Tigers were eventually routed and thousands surrendered to the Sri Lankan army. But hundreds of families of rebels who surrendered say they have still not heard from them.

Detailed video footage and eyewitness accounts emerged after the war showing what are alleged to be widescale extra-judicial killings of Tamils by the military in the final stages of the conflict.

A commemoration ceremony to mark the 10th anniversary of the end of the war took place in May

Based on that evidence, the UN and other rights groups have called on the Sri Lankan government to establish a war crimes tribunal to investigate the allegations of crimes against humanity, both by the military and the Tamil militants.

Successive Sri Lankan governments have resisted attempts to establish an international inquiry, saying it is a domestic issue and the allegations should be looked into internally. But virtually nothing been done to pursue justice after the war.

During a visit to northern Sri Lanka last year, I met a group of Tamil women and men protesting in the Tamil-dominated town of Kilinochchi. They were demanding to know the whereabouts of their sons, brothers, and daughters who had surrendered to the military.

Mr Rajapaksa vehemently denied that those who surrendered were killed in cold blood. "No I don't believe that," he told me. "Anybody who surrendered to the army was registered. Everything happened in a rush, everything happened in a chaotic situation," he said.

He said that about 13,000 Tamil rebels who were either captured or surrendered had been rehabilitated since the end of the war. He dismissed suggestions that some Tamil Tigers were being kept in secret prisons.

"No we did not run any secret prisons. It is not easy in this country to have secret places," he said.

Tamil women are demanding information on their relatives who they say surrendered to the army in 2009

His many critics would disagree. After the war, army camps were out of bounds to journalists, human rights officials, and relatives of the missing. There is still no independent confirmation of what happened to those who disappeared.

Minority Tamils and rights activists rejoiced when Mahinda Rajapaksa unexpectedly lost the election in 2015. They hoped that normal life would resume in the country and freedom of speech and media rights would be protected.

There has been peace in the years since the war ended, allowing some of scars to begin to heal. But the Easter bombings shattered that process - the attacks, along with a recent political crisis, have changed people's opinions.

Many Sri Lankans now say they are disappointed with government infighting and a blame game over the bombings between the current president, Maithripala Sirisena, and the prime minister, Ranil Wickremesinghe. In Sri Lanka, and around the world, people were shocked by the image of bungling incompetency the government projected.

That goes some way to explaining why many Sri Lankans are calling for a strong leader at a time of national crisis. Mr Rajapaksa believes he is the right man for the job.

Although human rights activists warn that the desire for a strong leader should not supersede civil liberties and media freedom, he is widely seen as the frontrunner. Gotabhaya Rajapaksa will be a hard man to beat.

- Published13 June 2019

- Published17 June 2011

- Published15 May 2019

- Published18 May 2019

- Published31 May 2019

- Published28 April 2019