Gay in South Korea: 'She said I don't need a son like you'

- Published

In South Korea, being LGBTQ is often seen as a disability or a mental illness, or by powerful conservative churches as a sin. There are no anti-discrimination laws in the country and, as the BBC's Laura Bicker reports from Seoul, campaigners believe the abuse is costing young lives.

It was a company dinner that changed Kim Wook-suk's life as he knew it.

A co-worker got drunk, slammed the table to get everyone's attention and outed 20-year-old Kim.

"It felt like the sky was falling down," Kim told me. "I was so scared and shocked. No-one expected it."

Kim (not his real name) was fired immediately, and the restaurant owner, a Christian Protestant, ordered him to leave.

"He said homosexuality is a sin and it was the cause of Aids. He told me that he didn't want me to spread homosexuality to the other workers," says Kim.

But worse was to come. The restaurant owner's son visited Kim's mother to give her the news her son was gay.

"At that moment, she told me to leave the house and said I don't need a son like you. So I was kicked out."

'Alienated and isolated'

Like so many other LGBTQ teenagers in South Korea, Kim Wook-suk had spent years carefully and quietly trying to hide his sexuality.

He was raised by a devout Protestant mother and taught that being gay meant burning in hell. He listened fearfully in church as the pastor preached that homosexuality was a sin and encouraging it would bring disease. That's not an unusual sermon in a country where around 20% of the population belong to conservative churches.

But despite being fired and made homeless because of his sexuality, he holds out hope South Korea can change.

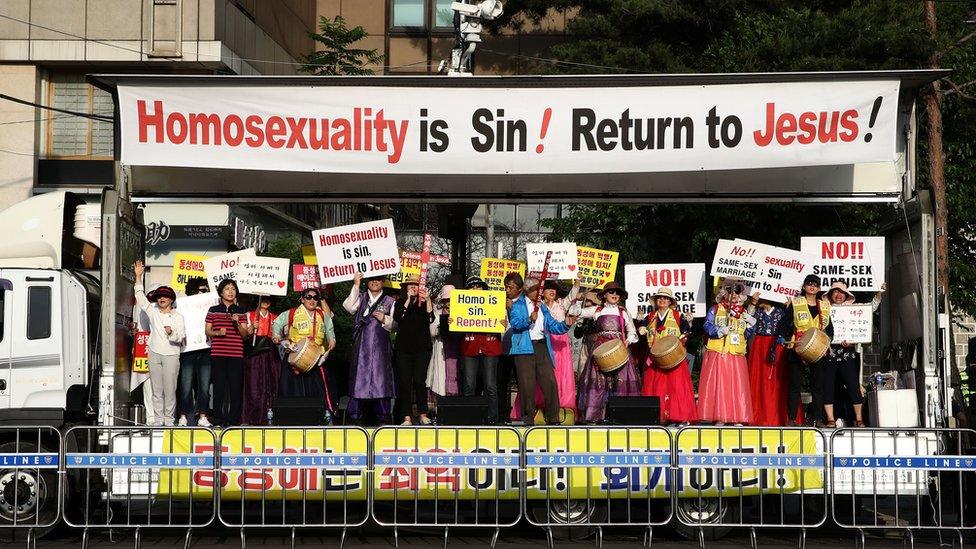

Christian anti-LGBT protesters are making their presence felt at gay events like here in Seoul

He proudly showed me his T-shirt with a special rainbow logo on it, one that calls for an anti-discrimination law. He believes this law will one day enable the LGBTQ community to come out into the open safely.

It may also save young lives.

A survey of under-18's in the LGBTQ community discovered that almost half - around 45% - have tried to commit suicide. More than half (53%) have attempted to self-harm. These figures have prompted the LGBT rights organisation Chingusai - Between Friends - to run a helpline.

"They usually talk about feeling alienated, isolated, feeling like they are a burden to someone," says Dr Park Jae-wan, who works in a hospital by day and volunteers to run the Connecting Hearts service at night.

"They feel distant as their teachers, friends, or family do not understand or are ignorant about what it means to be LGBTQ."

He believes a more permanent solution must be found to tackle the danger these young people face - and that involves fighting for a new law.

"We need to seriously think about how to embrace sexual minorities and think about what they need," he said.

Homosexuality may not be illegal in South Korea - since 2003 it is no longer classified as "harmful and obscene" - but discrimination remains widespread. Just under half of South Koreans don't want a gay friend, neighbour or colleague, according to one nationwide survey by The Korea Social Integration Survey.

Why holidays can be tough for S Korea's LGBT community

The proportion of gay and lesbian teenagers who have been exposed to violence is also high. A poll by the National Human Rights Commission of Korea found that 92% of LGBTQ people were worried about becoming the target of hate crimes.

Kim Wook-suk knows this all too well. His mother, he says, kept trying to "save him", but her actions meant he feared his own family at times.

"Using her church people, she tried to kidnap me multiple times to go through conversion therapy. I was forced to go through some of these therapies, however there were times I manage to avoid them and escaped."

Kim was always looking over his shoulder. He was alone in a park late at night when he was approached by a man who told him homosexuality was an unforgiveable sin and he should return home to his parents, before beating him with a bamboo stick.

He believes his own mother may have ordered the assault as a form of "shock therapy".

"Establishing an anti-discrimination law will send a message to society that people should not be treated differently based on their sexual orientations," says Cho Hyein, an LGBTQ lawyer at Hope and Law, when I tell her Kim's story.

"When a society sets principles, for instance, schools will be able to set responsive measures when kids are bullied. Right now in South Korea we don't have institutionalised measures to respond to discriminatory situations."

'We should stop them going to hell'

The LGBTQ community has been pushing for change since 2007, and their voices are becoming bolder.

But the same can be said for the opposite side. The Protestant Christian Community is so concerned that homosexuality will be accepted in South Korea that it has decided to hold its first "real love" event in Busan - just a month after the Queer Festival organisers were forced to cancel their own event in the city.

In a statement to the BBC, they said LGBTQ people were "unethical and abnormal" so their discrimination was "the right kind of discrimination".

Menorah said she felt a responsibility to stop LGBTQ people "from going to hell"

In September, this influential church group turned up at the Queer Festival in Incheon, South Korea's second biggest city, in their thousands.

They waved paper fans which said NO to homosexuality and YES to "real love". A huge screen was placed near the Queer Festival square blasting a warning video claiming that encouraging homosexuality would spread Aids and cost tax payers millions.

Getting to the Queer Festival square involved squeezing through lines of protestors offering a barrage of verbal abuse.

"Homosexuality is a country-ruining disease," one man told me. "If you commit a homosexual act, the country will perish."

Among the protestant Christians was Menorah. All day, until dark, she yelled through her megaphone from different positions around Incheon.

I asked her why she was shouting at these festival-goers.

"Because we are Christians. We are not here to blame other people, because we really love our neighbours. Just watching them going to hell is not true love. If we truly loved them, we should say the good news and stop them from going to hell."

I put it to her that perhaps she should listen to them rather than shout at them. But she was adamant.

"If we just proclaim our love of Jesus Christ softly, that is not going to work.

"True love is to stop them from going to hell. We should shout, because we don't have time. It is an emergency problem."

But as the protesters yelled, two foreigners opted to show their solidarity by kissing in public outside the Festival square.

Two foreigners opted to show their solidarity in Incheon by kissing in front of protesters

Last year, however, the event took a more violent turn. A number of protestors attacked the parade and prevented the festival goers from marching through the streets.

This year, the police recruited around 3,000 officers to protect just a few hundred people from the LGBTQ community who felt brave enough to join in the event. The presence of embassy staff from the world meant that the police had to ensure the safety of the event.

'The hate is overboard'

South Korea appears to be far less tolerance of the LGBTQ community than its East Asian neighbours.

Taiwan legalised same-sex marriage last year - the first country in Asia to do so. Meanwhile, Japan has elected its first openly gay lawmaker, and despite the current political opposition, a survey found that 78% of people aged 20 to 60 favoured legalizing same-sex marriage.

In July, Ibaraki Prefecture became the first of Japan's 47 prefectures to issue partnership certificates for LGBT individuals, raising hope that other prefectures would follow.

The difference in South Korea is the large number of influential protestant groups - although they are not all fighting against expanding rights for the country's LGBTQ community.

Pastor Lim Borah says conservative churches are using anti-LGBT sentiment to rally their supporters

Pastor Lim Borah, of the Sumdol Hyangrin congregation in Seoul, is from one of the few South Korean protestant sects which accept LGBTQ rights. She believes the vocal opposition to an anti-discrimination law is a way of rallying congregations just as the number of church-goers starts to decline.

"The church has used this to unite the congregation. In history, you can see how if you put forth a strong enemy, people will rally and unite behind it. So I think this is why the hate towards homosexuality is overboard."

She has been branded a heretic for her views.

"Regardless of religion, I think an anti-discrimination law should be a basic law for basic human rights. I just hope it becomes a reality soon."

Gay South Korean soldier: "I'm constantly afraid"

It may be Kim Wook-suk's best hope at a normal life. In his 20s now, Kim has a partner, and together they dream that one day South Korean society will accept them as a couple.

He is back on speaking terms with his mother, but they have to limit their conversations.

"She still can't accept me for who I am," he says. "She still thinks a man loving another man is wrong. But I no longer try to argue about this with my mom."