The nun who walks death row inmates to the gallows

- Published

Sister Gerard Fernandez: spiritual advisor, counsellor and friend to those on death row

In 1981 a Catholic nun from Singapore began writing letters to a female inmate on death row. It became an exchange that would last seven years.

The nun was Sister Gerard Fernandez and the prisoner Tan Mui Choo, a former student of hers who had been sentenced to death over one of the most brutal murders the country had ever seen.

She knew her as Catherine, a "sweet, simple girl" who came from a devout family and attended convent school.

Tan, along with her husband Adrian Lim and his mistress Hoe Kah Hong, were convicted of the ritualistic killing of two young children.

"She made a grave mistake," says the softly-spoken nun, now 81. "I was saddened when I first heard the news but I knew I had to see her."

For years Sister Gerard would visit Tan in prison, often spending long nights with her in prayer. The process, she said, allowed them to reconnect and build a deeper understanding.

"I was there to support Catherine and she knew she could talk to me," she says. "I think that freed her from her mental prison."

The nun was there until the end on 25 November 1988 - the morning of Tan's execution.

"Every person is worth more than the worst they have done," the nun says. "No matter one's sins, everyone deserves a death with dignity."

On her last morning, Tan wore a blue dress with a sash and matching shoes. "She was very calm," Sister Gerard recalls. The two women held hands on that final walk to the gallows.

She sang out Tan's favourite hymn 'How Great Thou Art' as she entered the hanging chamber.

"I heard her walk up the spiral staircase and felt the lever when it was pulled. The trap door opened and that was when I knew Catherine was gone."

Prisoners are seen inside Changi Prison

Located in Singapore's north-east is a sprawling high-security prison complex, a short drive away from its world-famous airport.

It houses the country's most serious criminal offenders and serves as a detention site for prisoners on death row.

Tan Mui Choo was one of 18 inmates who Sister Gerard Fernandez walked with to the gallows.

"A death sentence isn't something one readily accepts," she said.

"It takes time for a person to accept their fate and there will naturally be a lot of pain."

Sister Gerard continued her work with prisoners for the next 40 years. She believes it was part of her calling.

"Death row inmates need a lot of mental, emotional and spiritual support," she said.

"I wanted to help them understand that with forgiveness and healing, they would then be able to go to a better place."

'When I see God I will tell him all about you'

Years later another convict approached Sister Gerard after seeing her from his cell. "He said my presence brought him comfort," she recalled.

He asked to see her the day before he was to be hanged.

Sister Gerard considers it "the greatest privilege" to walk with inmates on death row.

"For someone to share their deepest sorrows and allow me into their hearts during their final moments is love and trust at the highest level," she said.

She remembers his last words: "I am going to see God in the morning and when I do, I will tell him all about you."

Sister Gerard Fernandez, 81, at her convent in Singapore's central Toa Payoh district

The Singapore Prison Service, which runs 14 prisons and drug rehabilitation centres, said support was "integral to the rehabilitation and reintegration of inmates".

"Sister Gerard Fernandez served as a volunteer [with us] for 40 years," a spokesperson told the BBC. "Her dedication, passion and sacrifice continue to inspire all of us, as well as many others who give their time and effort to support inmates and their families."

To many, it would have been a very different picture without Sister Gerard.

Speaking on condition of anonymity, the mother of a drug trafficker said the nun was a positive influence in her late son's life.

"Sister Gerard never judged him or gave up," she said, adding that she saw a huge change in his attitude. "His anger and resentment transformed into acceptance and remorse."

The elderly cleaner added: "She was very kind and was also there for me when I did not know what to do or how to feel."

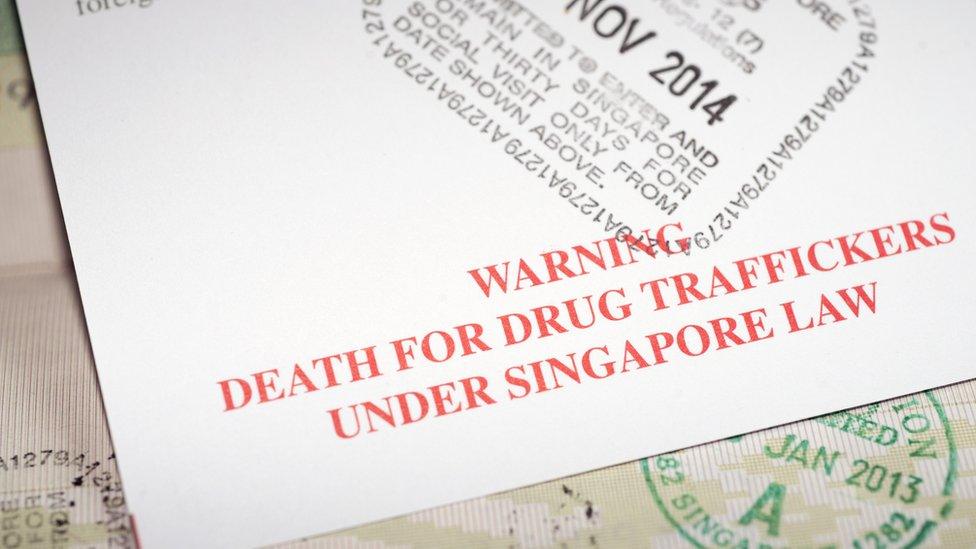

The death penalty remains a controversial and divisive topic in Singapore. The wealthy South East Asian city-state prides itself on its safe reputation and low crime rate.

While Singapore's government passed changes to capital punishment laws in 2012, official prison statistics show that 13 people, external were executed in 2018 - the highest figure in recent years.

Public polls also show strong support for harsh laws.

"There is generally high public support for the death penalty," said Singaporean Kirsten Han who co-founded the group We Believe in Second Chances, which actively campaigns for prisoners on death row.

"The death penalty is portrayed as a deterrent to crime," Ms Han said. "There is plenty of conditioning that leads Singaporeans to support such hard laws but very little open debate and information that reaches the wider public."

You may also be interested in...

The women who write to death row inmates

Human Rights Watch condemns the death penalty unreservedly.

"It is inherently cruel and blatantly violates international human rights norms," its Asia Deputy Director Phil Robertson said.

"The ruling People's Action Party in Singapore is not above using capital punishment [even as] more and more nations abolish the death penalty every year.

"There is just no acceptable rationale for a government putting someone to death."

Perhaps unsurprisingly, Sister Gerard Fernandez herself opposes the death penalty because "it takes away life".

"All life is precious," she says. "I respect our laws but I hope to see the death penalty abolished some day."

100 Women

What is 100 Women?

BBC 100 Women names 100 influential and inspirational women around the world every year and shares their stories. In 2019, the BBC recognised Sister Gerard Fernandez's work with death row inmates by nominating her for the list.

It's been a year of huge change around the globe, so in 2019 BBC 100 Women is asking: what could the future look like in 2030?.

Find us on Facebook, external, Instagram, external and Twitter, external and use #100Women

- Published10 April 2019

- Published14 November 2013

- Published19 July 2010

- Published10 July 2012