Pakistan pollution: Teens fight to save Lahore from toxic air

- Published

Nariman Qureshi's daughter Anya is one of the victims of Lahore's pollution problem

When Nariman Qureshi returned to her home in Lahore after a week-long work trip in early November, she discovered her five-year-old daughter Anya had spent two nights in intensive care.

The reason was her asthma, which had flared up severely. For Qureshi, it was the cost she had to pay for living in a city whose air quality is among the worst in the world, and which has spent last week either on top, or among the top five worst cities in the world to breathe in.

"I can't say for sure that we found out about Anya's asthmatic condition due to the worsening air pollution, or that the smog itself caused it, but what I do know is that since the 2017 smog season, she's been on asthma medication. I wonder if we were elsewhere, maybe that wouldn't have been the case," Qureshi says.

Delhi may have been hitting the headlines this week, but by the evening of 6 November, Lahore had taken the title of the world's most unbreathable city - with an Air Quality Index (AQI) of 551, forcing the provincial government to announce closure of all schools in the province on Thursday.

In fact, it was the third time in seven days it had topped the table with numbers which, according to America's Environment Protection Agency classification, fall into the "hazardous" category, and defined as "emergency conditions" likely to affect everyone in the area.

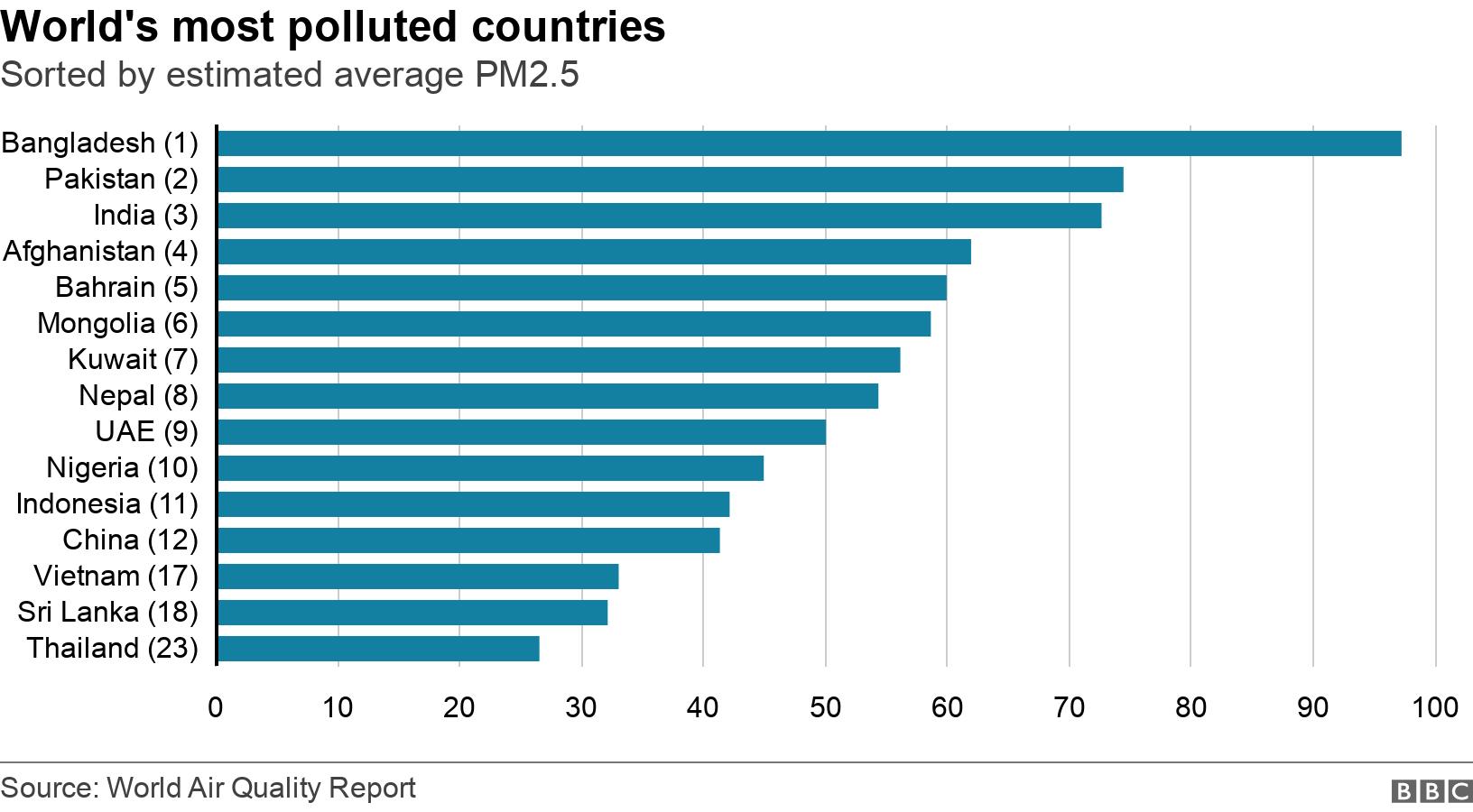

However despite Pakistan being ranked second worst for air quality in the world back in 2018, attempts by campaigners to force the government's hand and take some much-needed action have not met with much success.

But things could take a turn for the better for Qureshi, her daughter and rest of the nearly 12 million people living in Pakistan's second largest city if three teenagers achieve what they have set out to do.

In January, the early morning fog mixed with pollution to create a toxic smog over Lahore

On 4 November, Laiba Siddiqi, Leila Alam and Misahel Hayat filed a petition in Lahore High Court (LHC), requesting the court to declare government's smog policy and action plan "null and void" for being "illegal and unreasonable" and come up with a new plan.

The Chief Justice of the LHC heard the case himself and ordered provincial authorities to appear before the court next Tuesday for a response.

Ms Hayat, 17, a professional swimmer who represented Pakistan in the 2016 South Asian Games, told the BBC that as an athlete who trains outdoors the smog affects her particularly badly and she often finds it difficult to breathe properly.

Misahel Hayat is one of three teens taking on the politicians through the courts

"For swimmers, your lung capacity and ability to hold your breath is even more important than most other athletes, so knowing that 50% of those exposed to smog of these levels experience reduced lung capacity or that it is equivalent to smoking a pack of cigarettes a day is not encouraging," she says.

"Every day I and a group of other swimmers, most of them children, exercise outdoors and not all of them wear masks. I fear that if this situation continues in future years, the long-term effects will be much worse than even what we see today."

For 18-year old Ms Siddiqi, another petitioner, the experience of breathing in Lahori air is just beginning. Speaking to the BBC, she expressed her concern that she might not have seen the worst of it.

"I only moved to Lahore in September to pursue my studies and I am afraid that I haven't really fully experienced the worst of the smog yet. But I do see the alarm that permeates Lahori society when it comes to the smog season and the widespread investment in air purifiers and face masks."

Laiba Siddiqi hopes the petition will spark a conversation and build on the momentum of the city's climate march

The petition challenges the AQI measurement system adopted by the provincial body and accuses it of "underreporting the severity of air pollution".

This misreporting, says 13-year-old Leila Alam, the third petitioner, means she doesn't know "when to wear a mask and when it is all right to go out without it".

Watch how children in India's capital Delhi are affected by air pollution

Air pollution in Punjab, and Lahore in particular, has long been a menace to citizens and the government has don little in response.

When the Punjab's Chief Minister Usman Buzdar announced this week's school closures, Amnesty International's Omar Waraich took him to task, external, reminding the minister that his government has had more than a year to deal with the crisis.

But some at the top seem unwilling to take any responsibility - including Climate Change Minister Zartaj Gul Wazir.

She and Federal Minister for Science and Technology Fawad Chaudhry both blamed India on Twitter for Lahore's pollution.

Ms Gul Wazir went further - she questioned the AQI data, external and insisted Lahore's air was "nowhere as bad as being asserted by vested elements".

Sara Hayat, a lawyer with expertise in climate change law and policy and no relation of petitioner Mishael Hayat, says such buck-passing is pointless.

"There should be no contention on whether the smog situation is or isn't a public emergency. The government needn't waste any time disputing this," she says.

She says air pollution is a political issue and the authorities must act.

"The government should stop shifting the blame for smog on India and accept that Pakistan's transportation, poor fuel quality, industrial emissions and agriculture have placed us in a state of smog emergency," she adds.

Leila Alam - at just 13 - is the youngest petitioner

Ms Siddiqi, who helped organise a march against climate change in the city earlier this year, feels the High Court petition has made the right amount of noise.

"It has definitely helped to start a conversation. I feel our objective of maintaining momentum after the climate march is being achieved," she says.

Ms Hayat, the swimmer, hopes that the petition will force the government to do something.

"Unless we speak up about issues that affect us there can be no change, and this can only be sustained if the public is involved - especially young people," she says.

- Published6 November 2019

- Published4 November 2019

- Published4 November 2019

- Published4 November 2019

- Published1 November 2019