Sri Lanka election: Unity hard to achieve in divided country

- Published

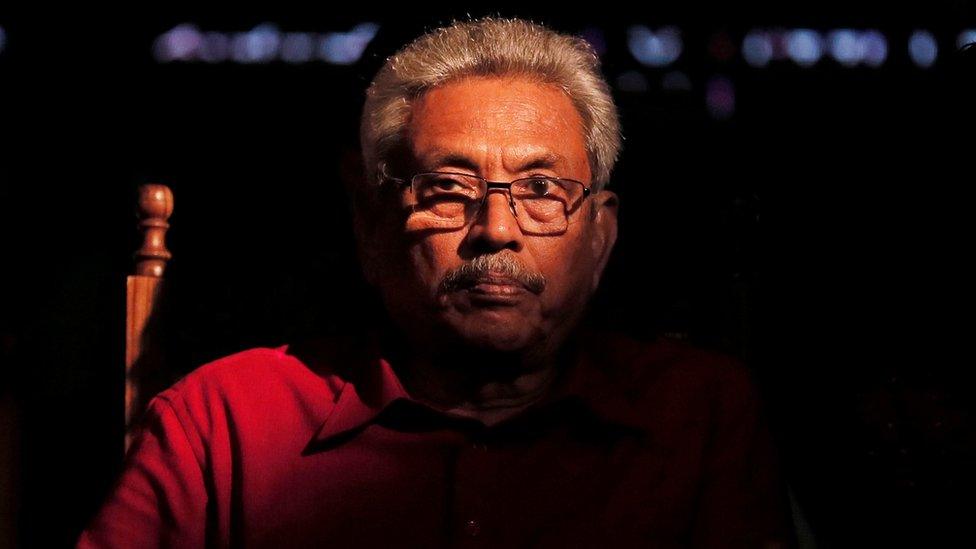

Gotabaya Rajapaksa was the country's defence secretary when Sri Lanka's decades-long civil war came to an end

As news broke of Gotabaya Rajapaksa's win, supporters and party workers gathered at headquarters. The mood was cautious but many here are relieved to see the Rajapaksa family back in office.

It's a family affair. Mahinda, Gotabaya's brother and the former President here for 10 years, is widely expected to be the next Prime Minister. The two brothers appear side by side on election posters and banners.

"It's a victorious day for us," Sagala Abhayawickreme, part of a group of lawyers who campaigned for the Rajapaksas, told me. "I worked for more than four years for this."

She clearly sees Gotabaya as a man who gets things done. "We saw him as defence secretary when he finished the 30-year war," she said, referring to the defeat of the Tamil Tigers 10 years ago, a decisive - if controversial - end for which Team Rajapaksa takes credit.

The Easter attacks simply wouldn't have happened on his watch, she added.

"I think it's a turning point in the history of Sri Lanka," said another Rajapaksa supporter, lawyer Janaka Arunashantha. "With economy and national security, I think the country will improve in every way in the next five years. We're very hopeful with him."

Mr Rajapaksa's supporters said it was a "victorious" result for them

Sri Lanka is still in shock, seven months after the bomb attacks by a cell of Islamist militants which devastated the island's economy, blew apart the island's fragile communal relations and was the final blow to public confidence in a government already tarnished by in-fighting.

But the news will be greeted with quiet dismay by many in the minority communities who voted overwhelmingly not for Mr Rajapaksa but his rival, Sajith Premadasa. They see him as a more liberal, inclusive choice. In many Tamil majority areas, such as the north, the vote was overwhelmingly for Mr Premadasa. Unifying the different communities - and pursuing post-war reconciliation - will be a daunting task.

In the last seven months, many Muslims say an underlying hate campaign against them in recent years, fuelled by hardline Buddhist groups, has become overt. They say their businesses have been boycotted, that they're openly insulted on the street, that their children are called names at school.

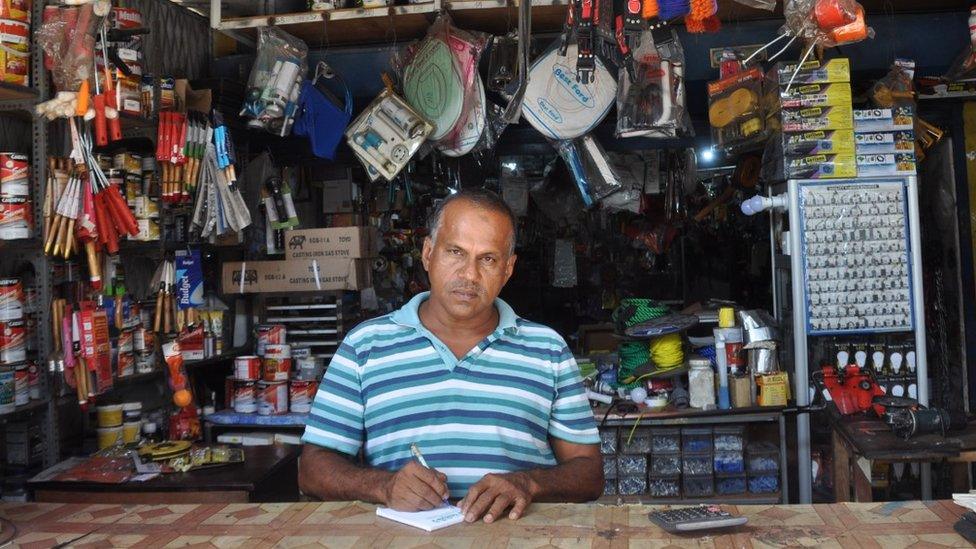

Many Sri Lankan Muslims said they "dreaded" a Rajapaksa victory

Many were anxious about speaking openly, but said in confidence that they dreaded a Rajapaksa victory. Mr Rajapaksa, widely seen as promoting the interests of the majority Buddhist community, is also accused by his critics of protecting anti-Muslim extremists.

One Muslim woman expressed the sense of anxiety I heard repeatedly from Muslims in the days leading up to the poll.

"If Gotabaya Rajapaksa wins, I see a lot of violence and racism ahead," she told me. "Most of these racist groups are aligned with this party."

Forgiving the Sri Lanka bombers and fighting to recover

On Sunday, the streets of Colombo were deserted and eerily quiet as the election news broke. Officials imposed a ban on public protests and gatherings. Political leaders too asked for calm.

Already, Mr Rajapaksa has promised unity. It's a response to the fears of many in the minority communities here that decisive leadership and tough action on security might be at the expense of their civil liberties.

Even if the political intention is genuine, the election results have shown how polarised this country is. Unity will be hard to achieve.

- Published17 November 2019

- Published25 November 2019

- Published3 October 2019

- Published13 August 2019

- Published11 October 2012