Japan mass stabbing: Accused admits murders but denies guilt

- Published

Mr Uematsu in court - he now has long black hair tied in a ponytail

A Japanese man has admitted killing 19 disabled people at a care home near Tokyo in 2016 but pleaded not guilty because he claims he is mentally ill.

Satoshi Uematsu, a former employee at the care centre, is charged with numerous crimes, including murder.

In interviews, the 29-year-old has said severely disabled people are harmful to society and should be killed.

The case is one of Japan's worst mass killings and has shocked people in a country where violent crime is rare.

The case has also raised questions about Japan's treatment of disabled people. Almost all of the victims will not be named at the trial - apparently because their relatives fear the stigma associated with having a disabled family member.

What happened in court?

At the opening of the trial, the former employee of the Sagamihara care home did not dispute he had stabbed his victims.

Satoshi Uematsu when he was detained in 2016

After the prosecution read out the details of charges, Mr Uematsu was asked whether "anything in the charges differs from the facts" and he replied "No, there isn't".

Despite his admission, the defence team pleaded not guilty, citing their client's mental state. They said he had been under the influence of drugs at the time.

"He abused marijuana and suffered from mental illness," his lawyer said. "He was in a condition in which either he had no capacity to take responsibility or such a capacity was significantly weakened."

There were traces of marijuana found in the defendant's blood after the attack.

Prosecutors insist he was mentally competent.

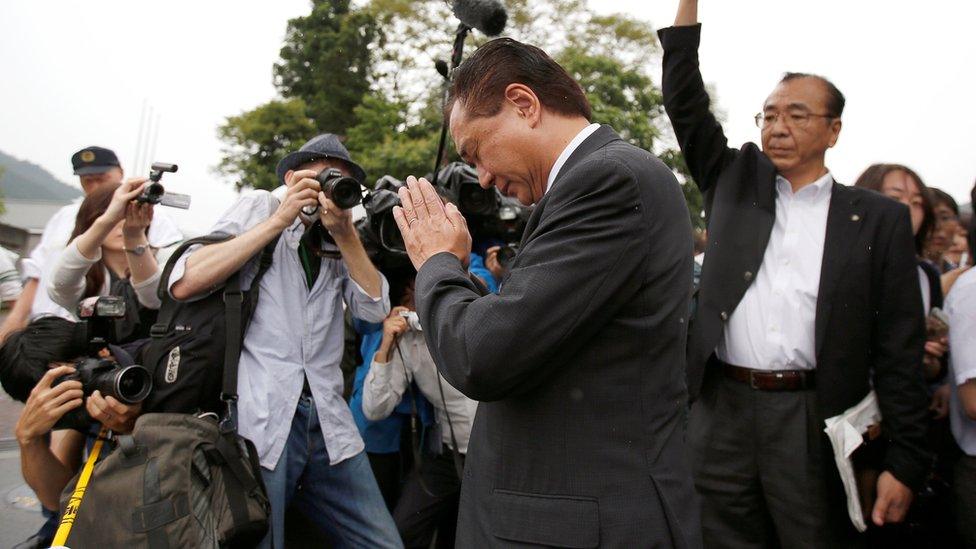

Members of the public formed long queues in the rain to attend the trial

Wednesday's proceedings were interrupted shortly after they began when the accused appeared to try to put something in his mouth and had to be restrained by security.

Mr Uematsu faces the death penalty if convicted. The court's verdict is expected in March.

How did the attack unfold?

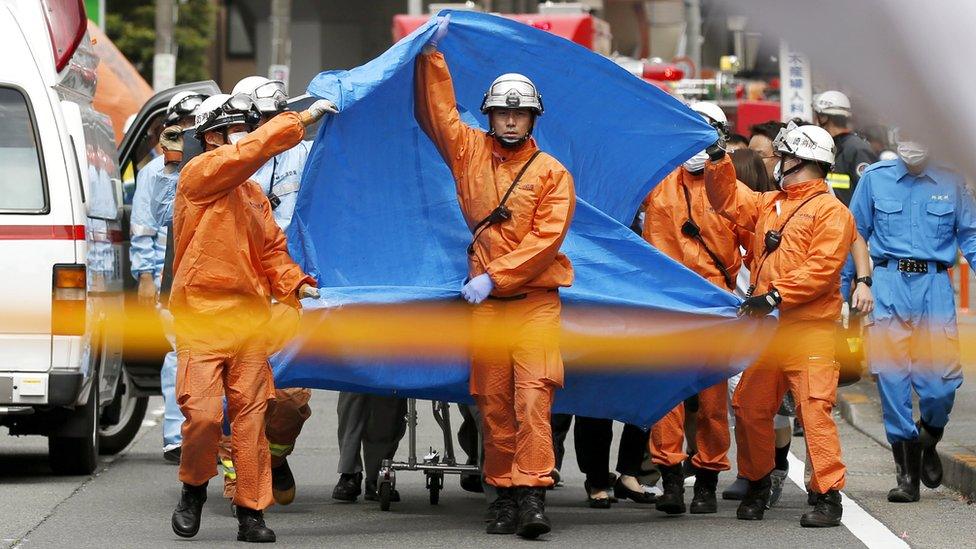

In the early hours of 26 July 2016, Mr Uematsu drove to the Tsukui Yamayuri-en care facility, located about 50km (31 miles) from Tokyo, armed with several knives, the court heard.

He entered one of the buildings by breaking a window and began attacking sleeping residents one by one in their rooms, prosecutors say.

His 19 victims were aged between 19 and 70, according to Japanese news agency Kyodo. Another 25 people were wounded, 20 of them seriously.

Soon after the attack, Mr Uematsu handed himself in at a police station.

"When Uematsu turned himself in, he was found carrying kitchen knives and other types of knives stained with blood," a Kanagawa prefecture official told reporters at the time.

Japan knife attack: Aerial shots show emergency crews at scene

The facility, set in extensive grounds, had about 150 residents at the time of the attack, according to local officials. Nine staff members were on duty at the time.

It later emerged that a few months before the attack Mr Uematsu had taken a letter to Japan's parliament saying he would kill 470 severely disabled people if authorised: "I want Japan to be a country where the disabled can be euthanised."

He was subsequently taken to hospital but released after two weeks. Since his arrest, he has shown no remorse.

In an interview with Japan's Mainichi Shimbun newspaper, he said there was "no point in living" for people with mental disabilities and that he "had to do it for the sake of society". He told Kyodo last month disabled people "bring misfortune" and are "harmful".

How has Japan responded?

The country was stunned by the Sagamihara care-home stabbings. Japan is considered to be one of the safest countries in the world, in part because of strict gun control laws.

The attack has also raised the issue of how disabled people are treated in Japan. To this day the identities of most of those killed have not been revealed by their families, apparently because they do not want to reveal they have a disabled relative.

Before the start of the court hearing, however, one mother whose daughter was killed in the attack revealed that her first name was Miho.

"I was proud of her as she had a lovely smile and was so adorable," the woman said in a letter to the press.

She said Miho, who was 19 when she died, had been autistic , externalbut good at getting along with others, Kyodo reports.

"Miho was living her life to the fullest, and I would like to leave proof for that. I want the name Miho to be remembered," she wrote.

- Published26 December 2019

- Published29 May 2019

- Published26 July 2016

- Published26 July 2016