Brothers' Home: South Korea's 1980s 'concentration camp'

- Published

Han Jong-sun still clearly remembers the moment he was abducted with his sister.

It was a beautiful autumn day in 1984, and Han, then eight years old, was enjoying a long-hoped-for trip to the city with his busy father.

But Han's father still had a few errands to run, and he decided the quickest - and safest - thing to do would be to leave the children with an officer at a police substation for a few minutes.

That police officer would tear the family apart.

"A bus stopped in front of the police substation and we were forced into the bus," Han recalls more than 30 years later. "A police officer exchanged unknown signs with the people who got off the bus.

"We had no idea where we were taken to. 'Daddy told us to wait here! Daddy is coming!' We cried and bawled.

"They started beating us, saying that we were too loud."

The bus was taking them to Hyungje Bokjiwon, a private facility that was officially a welfare centre.

But in reality, allege those who survived, it was a brutal detention centre which held thousands of people against their will - some for years on end.

Warning: Some readers may find some of these details upsetting

According to testimonies and evidence gathered from the site, detainees say they were used as slave labour at construction sites, farms, and factories during the 1970s and 80s. They were also allegedly tortured and raped, with hundreds dying under the inhumane conditions.

The facility at Hyungje Bokjiwon has been compared to a concentration camp, but its story is not widely known, and nobody - to this day - has been held accountable for the atrocities that reportedly happened within its walls.

For Han and his sister, their arrival was the start of a nightmare which would last three and a half years, and forever change the course of their lives.

'Social Purification Projects'

In the 1980s, South Korea was booming economically. It had achieved incredible growth, overcoming the scars of the Korean War in the 1950s, after which the Korean peninsula was split into North and South.

The whole country was in a fever ahead of the 1986 Asian Games and the 1988 Seoul Olympics, and the government began spurring on the nation's rebranding efforts.

But behind the so-called "Miracle of Han River" was a brutal and dark reality.

In April 1981, a letter arrived at the office of then-Prime Minister Nam Duck-woo. The letter, handwritten by President Chun Doo-Hwan, a former general who had seized power through a military coup a year earlier, ordered the authorities to "crack down on begging and take protective measures for vagrants".

Under the ordinance which allowed arbitrary detention of vagrants, social welfare centres were set up and buses with signs that read "Vagrants' Transport Vehicle" began to appear in large cities like Busan.

These welfare centres, mostly private facilities, were given subsidies from the government based on the number of people they took care of. Meanwhile, police are said to have been rewarded for "purifying" the streets by sending people to these centres.

Rough sleepers, disabled people, some orphan children, and even ordinary citizens who just failed to show their identification when asked, were allegedly taken to the centres as part of the "Social Purification Projects".

Hyungje Bokjiwon was one of the biggest of these welfare centres, not that far from a residential area in the south-eastern port city of Busan. The owner, Park In-guen, often insisted that they were there to feed, clothe and educate the vagrants.

On paper, each of the people who arrived at these centres should have only been kept inside for a year, given training and then released back into society.

The reality is that, for many, the next time they would see their friends and family again was in 1987, when the centres were forced to close after more than 30 escaped inmates blew the whistle on what was really happening behind their walls.

'Prison life'

Choi Seung-woo, another Hyungje Bokjiwon survivor, was 13 when he was taken off the streets on his way home from school.

"A police officer asked me to stop and started searching my bag," he told the BBC. "There was half a loaf of bread, a leftover of my lunch which was given from school.

"He asked where I stole the bread from. He tortured me, burning my genitals with a lighter. He kept beating me, saying he wasn't going to let me go unless I confessed to the 'crime'.

"Just wanting to go home, I lied. 'I stole it, I stole it. Please let me go…'"

About 10 minutes after he says he was forced to confess to a crime he did not commit, a freezer dump truck arrived, and he was forced inside. Choi says that was the start of his "prison life".

He spent almost five years in Hyungje Bokjiwon, in which time he says he saw - and experienced - brutal sexual and physical violence.

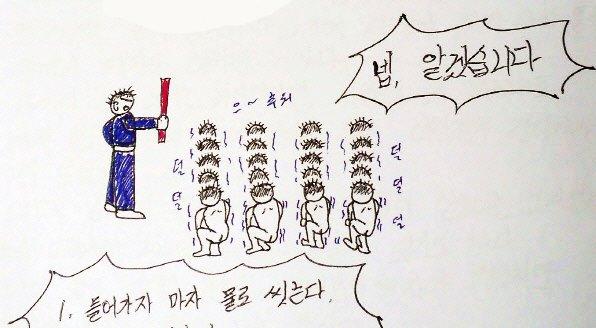

To keep control of the inmates, he says, the centre was arranged like an army. Choi was placed in a platoon, under the command of another inmate who had risen to become a platoon leader, given authority to "educate others" and tacitly allowed to use physical force.

"The platoon leader and some other guys took all of my clothes off and poured a bucket of cold water on my body.

"While I was trying to sleep, shivering naked, the platoon leader came again and raped me. He did that to me for three consecutive nights until I was transferred to a different platoon."

It took Choi just a week to realise that "people are being killed here".

"I saw a guy wearing a white robe dragging an inmate across the floor," he says. "He seemed dead. He was bleeding all over his body. His eyes were rolling back. The white robe guy didn't care at all and just kept dragging the man to somewhere.

"A few days later, a guy showed some sort of resistance by asking the platoon leader some forbidden questions like 'Why are we trapped in here? Why should we be beaten?'

"Four people came and rolled him in a blanket. They kicked him all over his body until he fainted, foaming at the mouth. People took him out wrapped. He never returned to the centre. I knew that he died."

More stories from South Korea

Aged just eight when he arrived, Han says he was the youngest in his platoon and was usually given manual work, like folding envelopes or making toothpicks.

He described the facility as "hell".

"The only thing I was provided from the centre was a set of blue training suits, rubber shoes, and a piece of nylon underwear.

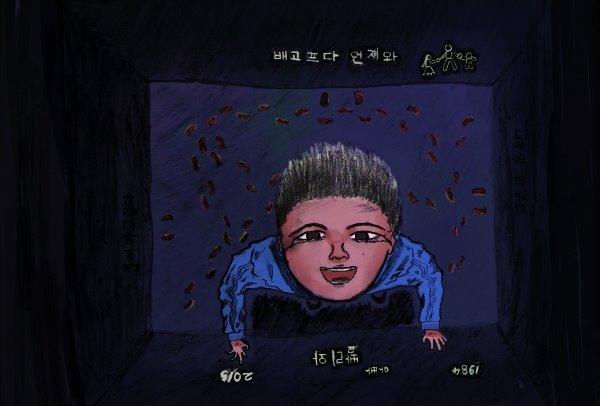

"I rarely had a chance to take a shower. Lice were all over my body. We had rotten fish and stinking barley rice every day, literally every day. Almost all of the inmates were malnourished.

"Four people slept in zigzags on a small bed. Rape occurred every night in the corner of the dormitory."

Some people dreamt of an escape, he says, adding that some even tried running away, but it was almost impossible to get past the guards and jump over a 7m (23ft)fence.

If you tried, failure was not an option.

"I knew that if I failed to escape, I would be beaten to death," Han said.

The mutual monitoring system made escape more difficult. Han says that sometimes mass escape was planned secretly, but there were always whistleblowers.

Prof Park Sook-kyung, of Kyung Hee University, who took part in a recent investigation into what happened at Hyungje Bokjiwon, pointed out the rule under which managers selected platoon leaders and gave them privileges helped maintain the whole detention system.

"The platoon leader I met said he had mixed feelings about what happened in the past. He said he saw himself as a bastard, but he did that to survive.

"If someone escaped, the platoon leader had to be punished instead."

Some parents tried to get their children back. Choi's family searched everywhere for their beloved son.

Choi says his family tried filing missing persons reports for him and his brother, who had also been taken to the centre, but police simply ignored them.

By the mid-1980s, rumours started spreading in Busan about people being beaten to death inside the so-called welfare centre.

Confident that his children were kidnapped and trapped in the facility, Choi's father knocked on the door of Hyungje Bokjiwon. His protest led the centre managers to release the brothers in 1986.

A year later, Park In-guen, who ran Hyungje Bokjiwon, was arrested. The centre was forced to close.

Life after release was not easy though.

Choi says his life was like that of a "beast". His brother took his own life in 2009.

"I was still a vagrant in the eyes of the society. I could only live a life of a vagrant, a beast. No-one held out their hands for us. We were branded by the state and the people followed. Whenever I said I was in Hyungje Bokjiwon, people were afraid of me."

Han, meanwhile, had lost contact with his sister and his father, who had also ended up in the centre.

Eventually, in 2007, he found them being treated in hospital for the mental trauma inflicted during their years at the centre.

Waiting for justice

A report into the centre by the then-opposition party published in 1987 found more than 500 detainees died under the inhumane treatment during the 12 years in which Hyungje Bokjiwon was in operation.

But nobody has ever been held to account for their deaths, nor the alleged human rights abuses which took place.

Park was eventually sentenced to two and a half years in prison only for embezzlement of state subsidies. He died of natural causes in 2016.

Two years later, the prosecutor who led the initial investigation into Hyungje Bokjiwon confessed that "there was external pressure by the military government to stop the investigation... and demand a short sentence for Park".

That same year, the then-prosecutor general Moon Moo-il formally apologised for the initial failures and requested that the Supreme Court review the ruling against Park, admitting that "no proper investigation was carried out".

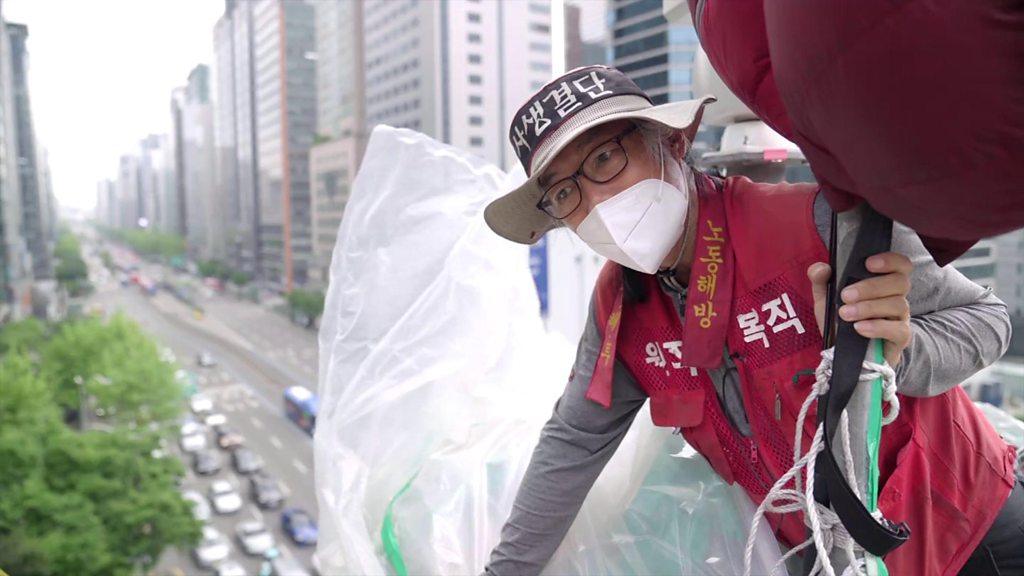

Han has never given up hope of a proper investigation: he has been protesting in front of the South Korean national assembly since 2012, demanding a state inquiry into Hyungje Bokjiwon. Choi joined him in 2013. Earlier this month, Choi staged a rooftop protest and was later taken to a hospital. He's still attending psychotherapy sessions regularly.

There is some hope, though: a new report by the Busan city government, seen by BBC Korean, clearly shows that Hyungje Bokjiwon was not the welfare centre it claimed to be.

Every one of the 149 former inmates - including a "platoon leader" - who took part in a survey said they were held by force. A third of them have a disability, and more than half failed to receive a proper education.

The team behind the report, Prof Park says, also believes "there was a torture room hidden inside Park In-guen's office".

The report also shows Park's centre benefited from the systematic segregation policy supported by the Chun administration during the 1980s.

There are now signs those locked up in Hyungje Bokjiwon may finally get the justice they have waited so long for: on 20 May, the South Korean National Assembly passed a bill, ordering the allegations be looked at again.

The next day, President Moon Jae-in, who took part in the investigation in 1987 as a member of Busan District Bar Association, said that he was "always sorry for failing to properly reveal the truth at that time", ordering a fresh investigation.

It has given Han a sliver of hope. He has even stopped his protest in front of the national assembly.

"I've always questioned myself. 'Did I really do something wrong to be taken to the hell-like facility?' If so, was it that grave that my whole life should be destroyed?

"I don't think I could forgive the government and the people related for letting it happen. However, if they succeed in revealing what really happened in the facility and make an official apology for the victims, I would try to forgive. I will try.

"My only wish is for my family to be reunited like in the past when I was an eight-year-old boy who just loved to play with daddy and sister."

Han and Choi, seen here at a recent protest, have never given up hope of a full investigation

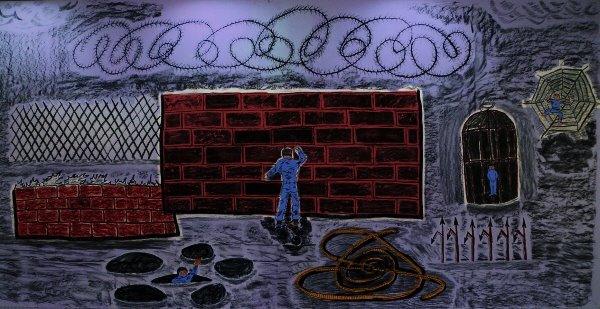

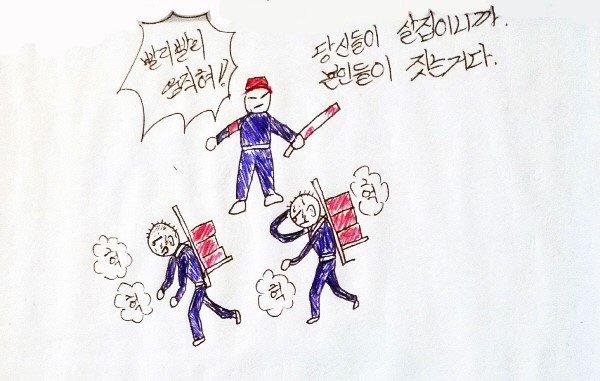

Illustrations based on drawings by one of the survivors of the facilities, Han Jong-sun, and edited by Davies Surya

- Published2 May 2020

- Published10 February 2020

- Published25 May 2020