Taliban peace talks: What to expect from the new round?

- Published

The United States and the Taliban mark the signing of their agreement in Doha.

US and Taliban officials involved in the signing of a historic agreement in February in Qatar studiously avoided referring to it as a "peace deal".

Over the weeks that followed it was clear why. While attacks by the insurgents on international troops stopped, fighting with Afghan security forces continued.

The agreement set out a provisional timetable for the withdrawal of foreign forces from Afghanistan, providing the Taliban prevented international jihadist groups such as al-Qaeda from using their territory to attack the US or its allies.

It also committed the Taliban to beginning direct negotiations for the first time with the Afghan government and other Afghan leaders to try to reach a political settlement.

Those talks are now set to begin in Qatar this week, aiming to put an end to two decades of war and the loss of thousands of lives. They were meant to begin in March, but instead were held up for months by wrangling over a prisoner exchange plan.

The US-Taliban agreement promised "up to 5,000" Taliban prisoners would be set free by the Afghan government ahead of the negotiations, in return for 1,000 members of the security forces held by the militants.

In a sign of how uncompromising the Taliban have been throughout the process, the group insisted that exactly 5,000 prisoners should be freed, and that only detainees named on a list by the group would be counted.

The government, which hadn't been part of the US-Taliban talks, resisted. Afghan officials hoped they could extract some concessions out of the Taliban in return for the prisoners. But instead the Taliban raised the levels of violence.

Tens of thousands of Afghan soldiers have been killed and injured. This is their story

Annexes to the US-Taliban agreement, never made public, were intended to set some limits to the fighting. According to a well-placed source, the Taliban were allowed to continue operations in rural areas, but not in major cities.

Meanwhile, the US would only be allowed to conduct air strikes within a specific distance of active battlefield operations, not on Taliban fighters resting in camps or villages. This left the Taliban free to increase attacks on Afghan forces manning more remote checkpoints.

In any case, the group, at times, did carry out large-scale attacks in some cities, perhaps waiting to see how the Americans would respond, while upping the pressure on the Afghan government. There has also been a spate of targeted assassination attempts on pro-government figures, many of which have gone suspiciously unclaimed.

Eventually President Ashraf Ghani relented, freeing all but 400 of the inmates, who he alleged were responsible for particularly serious crimes.

Even after the decision was made to release them, further delays followed. In part because the Afghan government demanded a number of soldiers held by the Taliban should also be freed, in part because France and Australia objected to the release of a handful of prisoners who had been involved in killing their nationals.

The US, however, grew increasingly frustrated, and the remaining prisoners were freed last week, while plans have been drawn up to send the seven who are linked to attacks on foreign forces to Qatar, where they will be kept under surveillance.

What is at stake in the peace talks?

The next stage of the process, talks between the Taliban and Afghan government, or "intra-Afghan negotiations", will revolve around an actual "peace deal".

US troops in Logar province this July

Officials, and indeed ordinary Afghans, hope a ceasefire can be agreed although, until now, the Taliban have seemed determined to continue fighting until their demands are met.

They see violence as their best form of leverage, and are cautious of allowing their fighters to lay down their weapons, in case it becomes difficult to redeploy them or they drift towards rival militants in the Islamic State group.

Negotiators will also try to establish some kind of agreement on a political future for the country.

The task seems daunting. How to reconcile the competing visions for the country? On the one hand the "Islamic Emirate" that the Taliban adhere to, on the other, the more modern, more democratic Afghanistan built over the past two decades.

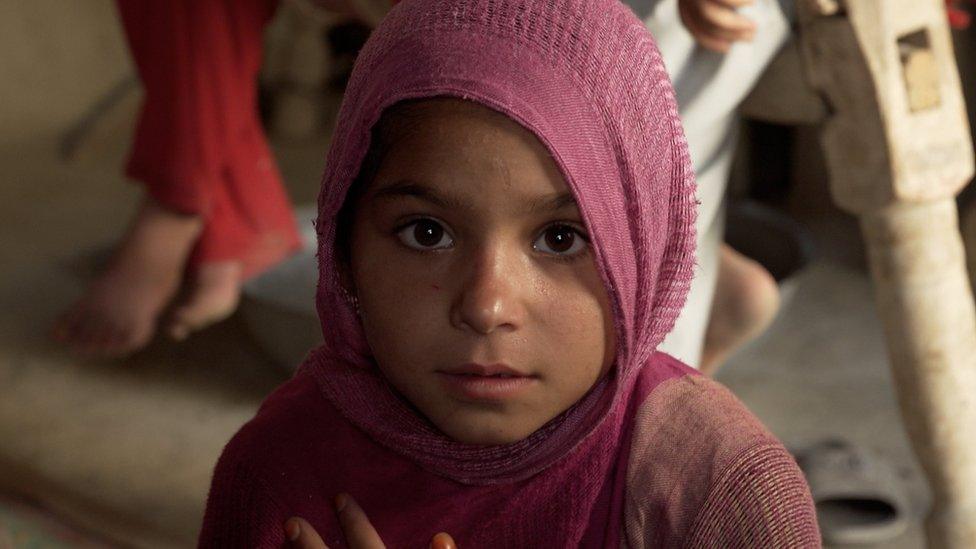

When the Taliban controlled most of the country, from the mid-1990s until the US-led invasion in 2001, they ruled following an austere and often brutal interpretation of Sharia law. Among other restrictions, women were prevented from working or going to school.

The Taliban insist they don't oppose women's education, but also often refuse to accept they ever did. Statements committing to women's rights are qualified by caveats around adhering to "Islamic values". Many Afghans are sceptical about how much they have changed.

Zan TV presenter Ogai Wardak: "If the Taliban come, I will fight them"

Leading journalist Farahnaz Forotan founded an online campaign "My Red Line", highlighting the fragile personal freedoms many women believe must not be comprised. "The Taliban have to accept the reality of today's Afghanistan, if they don't, these peace talks won't have a real result," she told the BBC.

One diplomat who has been closely following the peace process said the Taliban had been deliberately vague in setting out their political vision. In an interview last year, I asked the group's chief negotiator at the time, Abbas Stanikzai, if they would accept the democratic process.

"I cannot say…" he replied, "there are many types of government that were tested in Afghanistan. Some people want the emirate system, some people want a presidential form of government."

He then added that whatever system "the majority" involved in the negotiations were in favour of, the Taliban would agree to.

Bringing US troops home

Meanwhile, American troop numbers are already being reduced. According to the US-Taliban agreement, all US forces will leave by May 2021, if the Taliban fulfil their commitments on al-Qaeda, and begin talks with the government. The withdrawal, in other words, is not contingent on a settlement being reached between the Afghan government and the Taliban.

Ahead of elections later this year, US President Donald Trump has repeatedly signalled his interest in bringing home American forces as soon as possible. He has already promised to reduce the number to 5,000 by November, the lowest levels since the invasion began in 2001.

Warnings from UN and even US officials that links between the Taliban and al-Qaeda have yet to be broken don't seem to be disrupting that goal.

Meet Fatima and Fiza, some of the women removing landmines in Afghanistan

One observer told the BBC it was clear the primary goal of President Trump's administration was to obtain assurances from the Taliban on counter terrorism co-operation, whilst women's rights or human rights were not considered a priority.

A number of European countries, however, are understood to have concerns about the speed of the withdrawal and its implications.

Some analysts have noted that were the Democratic candidate for president, Joe Biden, to be elected in November, he may be more open to slowing down the withdrawal process. There has been suggestion that Afghan President Ashraf Ghani may have deliberately been stalling on the prisoner release plan, waiting to see if there is a change in US leadership.

Who will govern Afghanistan?

With American troops on their way out many supporters of the Taliban believe they will be able to determine what kind of society should now be created. These talks will provide the first tangible insight into the group's vision. So far, their leadership has talked both about the need to create an "Islamic government" but also an "inclusive" one.

While discussions are ongoing, the Taliban are likely to suggest the formation of an "interim" government which they will form part of, though how that would work, and where it leaves the current political leadership, remains unclear.

The view from Lashkar Gah province on whether peace with the Taliban is possible

Despite their hard-line stance in the past, Taliban officials have stressed they value international legitimacy. In the 1990s only a handful of countries recognised their regime, and they were unable to capture the entire country. Even now, despite contesting significant amounts of territory, the Taliban have not been able to retain control of any urban centre.

The European Union in particular has stressed that if any future regime doesn't adhere to international standards on human rights, investment and aid could be withheld.

Given the pace of progress so far, the talks are likely to be protracted, and their result is uncertain. However, after years of conflict have produced little more than stalemate on the battlefield, they represent at least an opportunity for peace for Afghans.

- Published14 August 2020

- Published27 February 2020

- Published16 September 2019

- Published30 July 2019

- Published11 March 2019

- Published14 September 2018

- Published6 July 2019