Yoshihide Suga: The unexpected rise of Japan’s new prime minister

- Published

Yoshihide Suga (third from left) celebrates after winning the party leadership

Shinzo Abe was Japan's prime minister for so long that people around the world came to recognise his face and perhaps even knew how to pronounce his name. So, should we all now be learning how to say Yoshihide Suga? That is a difficult question to answer.

A month ago, there were very few who would have predicted what we are now witnessing. Firstly no one expected Mr Abe to go, certainly not before his beloved Tokyo Olympics. Even fewer would have guessed Mr Suga as his replacement.

The 71-year-old is known in Japan as Mr Abe's fixer, the backroom guy who gets stuff done.

When asked recently whether he thought of himself as a nice guy, Mr Suga responded: "I am very nice to those who do their job properly."

His public face is that of the unsmiling and seemingly charmless government spokesman. His nickname among Japanese journalists is the "Iron Wall", a reference to his refusal to respond to questions he doesn't like.

So how is it that Mr Suga is now suddenly Japan's new prime minister?

According to economist and long-time Tokyo resident Jesper Koll, Mr Suga was chosen by Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) bosses, the faction leaders who wield power behind the scenes, because they saw no obvious alternative.

"This is obviously an election in smoky rooms right inside the LDP," he says. "The public had no voice in this choice of the prime minister of Japan.

"In the end, you're only any good to your party if you can win victories in public elections. So, he is under pressure. He is going to have to prove himself to the party and to the Japanese people that he deserves to be prime minister," says Mr Koll.

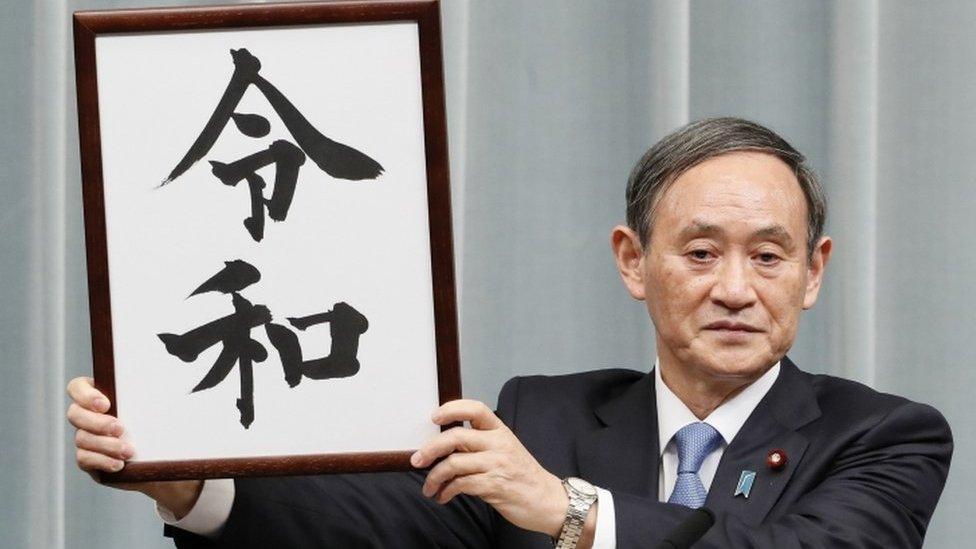

Mr Suga was nicknamed "Uncle Reiwa" after unveiling Japan's new era name

Mr Suga is clearly not without political skills. He has served as Japan's chief cabinet secretary for longer than any of his predecessors. He has a reputation for toughness and discipline and for understanding the machinery of Japan's byzantine bureaucracy. But are those the sorts of skills that win elections?

Professor Koichi Nakano from Tokyo's Sophia University thinks not.

"He rose to power because he has the political skills of intimidating opponents, including the press and dominating the scene through backdoor dealings and controlling the bureaucrats quite well," he says.

"But when it comes to the public face of the party, when the lower house election needs to be called within a year, he's really unsuited because he's not very eloquent."

That lack of eloquence was on display as Mr Suga made his victory speech on Monday. In ponderous tones with long pregnant pauses he promised the following.

"I want to break down bureaucratic sectionalism, vested interests, and the blind adherence to precedent."

But Mr Koll is someone who knows Mr Suga personally and he says we shouldn't be so quick to dismiss him.

"Here is a man who gets up at 5am in the morning, does 100 sit ups and then reads all the newspapers," he says.

"By 6:30am, he's starting meetings with business people, with advisers, with outside economists. He absorbs like a sponge and wants to get things done for the country. He's not interested in any of the glitz or bling that comes with the government."

Observers say Mr Suga eschews the "glitz or bling" of government

The new premier's eschewal of "glitz and bling" is put down to his humble origins.

Mr Suga was born in a small village in the snowy north of Japan, the son of a strawberry farmer. According to a 2016 biography, he couldn't wait to escape the rural backwater.

At 18 he left for Tokyo. There he worked in a cardboard factory saving to pay his own way through university. That sets Mr Suga apart from most of his predecessors, like Mr Abe, whose father was Japan's foreign minister, and grandfather prime minister.

Mr Suga's "origins" story is a good one, but according to Professor Nakano it makes him extremely vulnerable in the sometimes vicious factional struggles inside Japan's ruling party.

"Because Mr Suga comes from a humble background, he really doesn't have his own power base," he says.

"He doesn't belong to any faction. He rose to power because he was Mr Abe's preferred choice. And the party bosses rally behind him in an emergency situation. But once the emergency situation is gone and once the party bosses start to realise that they are not getting all they wanted, I'm sure there is going to be a power struggle."

There are many well connected "young pretenders" waiting in the wings, waiting for Mr Suga to make a mistake. And there are many things that could go wrong. Before he announced his departure, Prime Minister Abe's approval rating had fallen to 30%, largely over discontent at the way he's handled the Covid-19 crisis.

Former premier Shinzo Abe bids farewell to staff members

Mr Abe's greatest achievement was to give Japan a long period of political stability. Before his election in 2012, Japan had seen 19 prime ministers in the previous 30 years. It was called "the revolving door", and some worry Japan is now poised to return to factional infighting and short-lived governments.

"It does seem to be the case that after a long-serving prime minister, we get short-lived ones," says Kristi Govella, a Japan watcher at the University of Hawaii.

"I think it's likely we will now enter a period of more short-lived prime ministers. It's not clear if they'll be every 10 months or rather every two years. It would certainly be beneficial for Japan if it were not a different person every year."

For Prime Minister Suga, those are not reassuring words. He has a lot to prove, and probably not very long to do so.

- Published14 September 2020

- Published28 August 2020

- Published28 August 2020