Philippines Troll Patrol: The woman taking on trolls on their own turf

- Published

Gina was alarmed at the online abuse she saw in the Philippines

The Philippines is playing a key role in the wave of disinformation sweeping the world. So-called troll farms are being used to create multiple fake social media accounts that post political propaganda and attack critics. But a group of people calling themselves the Troll Patrol are trying to use their own tactics against them, as the BBC's Howard Johnson reports.

In 2016, Gina - not her real name - and others, watched with alarm as a group of Catholic schoolgirls in the Philippines came under attack from online trolls.

The girls had been filmed and photographed standing on a street in the capital Manila in their uniforms, chanting: "Marcos is no hero! Marcos is no hero!"

They were angry that former Philippine dictator Ferdinand Marcos had just been buried in a nearby hero's cemetery with military honours.

In the 21 years he ruled, billions of dollars of public money went missing while thousands were arrested and tortured for opposing his regime.

But his family have remained both politically influential and popular and are closely aligned to the current President Rodrigo Duterte.

Within hours of the photos being posted on the school's Facebook page, and then widely reshared, comments began to appear defending the Marcos legacy and attacking the girls' actions. Some of them were from genuine accounts, but many were from pro-government trolls using fake accounts.

The pictures and videos were widely shared

"If Marcos is no hero, I would say most of you are no virgins and that's the trend of young girls nowadays," said one. There were also rape threats.

"We're talking about kids here. Nobody was doing anything about it," says Gina. "We realised that we should beat them at their own game."

Gina and a group of equally-concerned individuals, who would go on to be known as the "Troll Patrol", took action.

Much like the trolls, the group began creating fake Facebook accounts - Facebook doesn't require photo ID proof of identity - so they could defend the girls without risking personal attacks themselves.

They created scores of accounts whose posts were designed to counter the narrative of the online pro-government bullies through logic and reasoning.

Night-after-night the group would log into Facebook scanning for threatening posts or abusive behaviour and begin posting their counter-comments.

"We realised that if [opponents] feel that you are part of the group that actually opposes the views of government, people would never listen to you," says Gina.

"You have to make them feel that you are actually part of their circle who just happened to have a change of opinion. You can educate the people and at the same time you can say whatever you wanted to be able to protect the people who were being cyber-bullied."

Within a week the controversy over the protest began to die down, but the problem of trolling has far from gone away in the Philippines. And it's not just used to support President Duterte and those aligned with him, it's also used to silence critics.

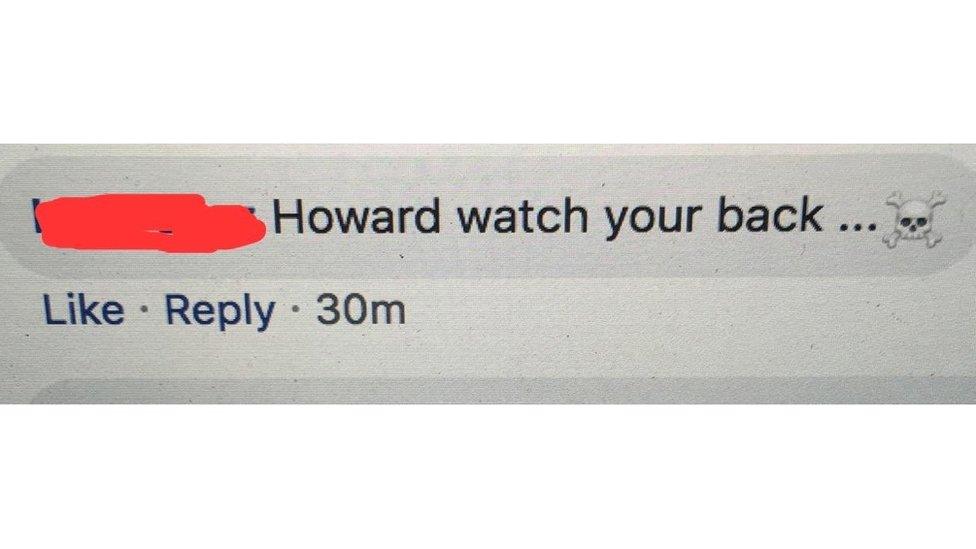

Journalists, human rights defenders and politicians have all reported receiving systematic abuse and death threats. I too have received threats online for my reporting, saying I would be "hunted down" and "beaten". One comment read "watch your back", accompanied by a skull and crossbones emoji.

Many of the most ardent trolls are supporters of the president - they call themselves DDS (Diehard Duterte Supporters), a play on the lettering of the Davao Death Squad, an execution squad, which according to the United Nations, killed more than 1,000 people in the city in the southern Philippines while Duterte was its mayor.

Mr Duterte has even admitted paying people to promote him or defend him on social media, though he insisted he only did so during his successful 2016 election campaign.

According to Presidential Communications Operations Office (PCOO) undersecretary Jose Joel Sy Egco, the government has never used paid-for "keyboard warriors" to attack critics while Mr Duterte has been in office.

Mr Egco told the BBC that online troll threats come from a "myriad of sources", which could include "somebody's neighbours" to "any local official you had a brush with recently".

There have been reports in the Philippine media about "troll farms" - centres where people are allegedly paid to write abusive comments on peoples' social media accounts. I asked Mr Egco what the government had done to investigate these claims:

"If you're asking us, if you're asking me as a government official here, I am definitely against any such practice, if there's any at all."

Mr Egco denied any government involvment

I hadn't asked Mr Egco if the government was behind the troll farms, but he went on to elaborate:

"In government, we are very diligent in spending our budget and we don't have budgets for those kind of things. Maybe some people did that in the past and maybe some people are still doing it right now, but definitely I tell you, in all honesty, and I swear to God, I myself do not believe in such."

Mr Egco said that his team had received "a lot of complaints" by media workers about cyber-harassment and cyber-bullying and that the department had investigated the cases but had run into a brick-wall when social media companies refused to disclose information on the people posting the comments.

Facebook wouldn't confirm whether it had any plans to make it harder for people to set up fake accounts, but a spokesperson said the company was "committed to removing content that violates our policies, disrupting coordinated inauthentic networks, and limiting the spread of misinformation".

This week the company took down two networks based in the Philippines and China for violating their policy on "foreign or government interference." The networks, which included more than 200 accounts, targeted Filipino Facebook users with, among other things, content supportive of President Rodrigo Duterte.

Despite the online abuse, I have never been threatened in real life in the Philippines. But online troll behaviour can precede deadly outcomes. Recently two human rights defenders, who had been repeatedly trolled and threatened online were killed within a week of each other.

On 10 August, unidentified assailants killed peasant leader Randall Echanis, 72, inside his home in Quezon City, in Metro Manila. Then on August 17 unidentified gunmen fatally shot Zara Alvarez, a legal worker for the human rights group Karapatan. The group says 13 of their activists have been killed in the past four years.

Within minutes of Ms Alvarez's killing, another member of Karapatan, Clarizza Singson, received a message on Facebook warning that she "would be next."

The group say they are the repeated targets of "red-tagging," in which the authorities and online trolls label them as Communists, linking them to the country's decades-old Communist insurgency.

And rights groups fear a newly passed Anti-Terrorism Act could weaponise the troll's posts.

Protests were held against the new terror law in Manila earlier this year

The law allows for the detention of 'terrorist' suspects for up to 24 days without charge. An Anti-Terror Council, made up of Duterte appointees, has the power to designate people as suspected terrorists, subject to surveillance for 60 days and arrest, based on mere accusations.

Supporters of the law say it is needed to bolster efforts against ongoing armed insurgencies mainly in the south of the Philippines.

But rights group Amnesty International says even the mildest government critics can be labelled terrorists, based on accusations thrown online by anonymous pro-government trolls.

"In the prevailing climate of impunity, a law so vague on the definition of 'terrorism' can only worsen attacks against human rights defenders," said Nicholas Bequelin, AI's Asia-Pacific Regional Director.

Gina says she and the Troll Patrol make no apologies for adopting similar tactics to get their message across.

"We justify [our] actions because they are all part of free speech, which we really hold in high regard," says Gina. "It would have been easy to report the pro-government accounts. But honestly, let them say whatever they want to say. Bad speech can only be fought by better speech. I don't really believe in censure."

And with more Filipinos expressing free speech, Gina believes the need for the Troll Patrol is diminishing.

"Nowadays, we no longer hide under these personas," says Gina. "We still speak out against abuses whether by the administration or the opposition. But this time, we speak as ourselves."

- Published17 October 2018

- Published4 August 2020