Far from home, Rohingya refugees face a new peril on a remote island

- Published

Tens of thousands of Rohingya refugees have fled Myanmar for Bangladesh

After fleeing a brutal crackdown which left thousands dead in their homeland of Myanmar, the Rohingya are once again under threat.

In Cox's Bazar, the massive refugee camp in Bangladesh to which many of the Rohingya refugees fled, violence and drug and human trafficking are on the rise. The Bangladeshi government has begun relocating hundreds of the refugees, against their will, to the small remote silt island of Bhasan Char.

On the first visit to the island by journalists, the BBC went to investigate what the future holds for the tens of thousands of Rohingya still living in limbo.

Children on their way home in Cox's Bazar camps

It's been six months since 55-year-old Rashida Khatun has heard from her children. Khatun and her family live in Cox's Bazar, but in February, before the coronavirus had fully taken hold in Bangladesh, two of Rashida's children set off on a perilous journey.

Driven by their belief in a better future, her 17-year-old daughter and 22-year-old son boarded a small fishing vessel with two dozen other Rohingya refugees and began the 10-day journey from Cox's Bazar to Malaysia.

Rashida Khatun

Sitting in her makeshift house of bamboo and plastic, with a white head scarf draped over her head and shoulders, Khatun described how her family fled from their homeland of Myanmar in 2017 after the military attacked her village in Maungdaw and burnt down her house.

Three years ago, a military operation in Myanmar destroyed entire Rohingya Muslim villages. UN investigators say as many as 10,000 people were killed and more than 730,000 Rohingya fled the massacre for Bangladesh. The UN called it a "textbook ethnic cleansing".

In February, Bangladeshi authorities began erecting barbed-wire fences around the camps

After years of living in temporary shelters, and with no hope of returning to their ancestral homeland, Khatun's son and daughter had become desperate to escape the escalating violence and lack of opportunities in the camps. So they decided to flee to the Muslim majority country of Malaysia.

"One of my relatives in Malaysia phoned me last year. He said that many Malaysian men want to marry Rohingya women," Khatun said.

"He assured me my daughter would be able to get married there and that my son would be able to get a good job."

A boat carrying Rohingya refugees is detained by authorities off the coast of Malaysia

Travelling by boat from Bangladesh to Malaysia has become the most common route out of the camps for young Rohingya, but it's a treacherous journey. In the same week Khatun's children departed, a fishing boat carrying dozens of refugees capsized just off the coast of Bangladesh. Fourteen people died.

After 10 days at sea, Khatun's children - who we have not named to protect their safety - made it within sight of the Malaysian coast. But they were being tracked by the Malaysian Navy.

Refused permission to dock by the Malaysian authorities, their tiny fishing vessel was left stranded for a month floating in the Andaman Sea. Eventually, Bangladesh's coast guard, bowing under the pressure from local media and human rights groups, intervened.

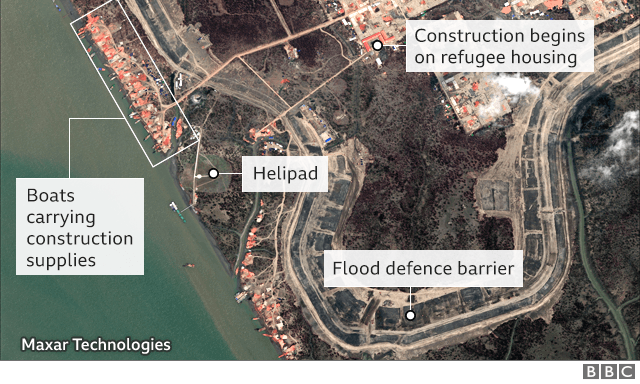

In 2018, the authorities began building on the new emerged island of Bhasan Char

Along with hundreds of other refugees who had also been refused entry to Malaysia, Khatun's children were not allowed to return home to the camps of Cox's Bazar, but were instead taken to the small island of Bhasan Char, in the Bay of Bengal.

Back in Cox's Bazar, Khatun received a call from an unknown number. "My daughter sounded very anxious. She was crying when she told me that she was being taken to an island named Bhasan Char."

It was the last time she spoke to her daughter.

The Island

The island of Bhasan Char, located 60km (37 miles) off the coast of Bangladesh, emerged less than 20 years ago from the sea. Situated less than 2m (6ft) above sea level, the island is made entirely of silt, Himalayan sediment washed down river and into the sea.

For the past three years, the authorities have been building a new town, at a cost of $350m (£270m). Their aim is to relocate more than 100,000 refugees in order to ease tensions within the camps.

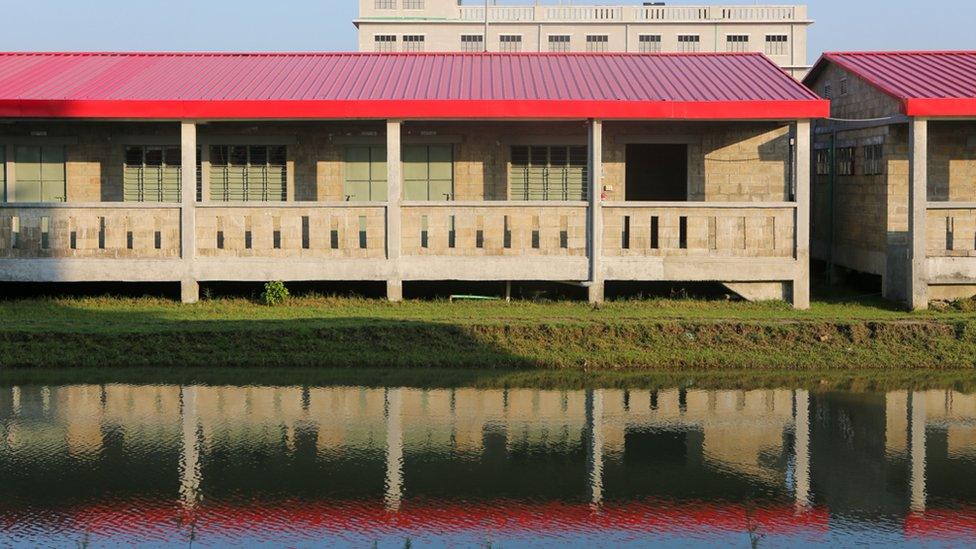

The construction of 1440 four-person houses and a huge tidal surge barrier began in 2018

Bangladesh's Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina has frequently defended her government's plans, urging the international community to understand that, with over a million refugees living in Cox's Bazar, the escalation in violence as well as both drug and human trafficking shows the camps are no longer safe nor sustainable.

"The crisis is now becoming a regional threat. Besides increasing congestion and environmental degradation, it's also challenging health and security in the area," she said at the UN General Assembly last year.

A bird's eye view of the red roofed houses on Bhasan Char

But for many Rohingya, Bhasan Char is closer to a prison than a refuge. All of the 306 refugees living on the island, including Khatun's two children, were relocated to the island against their will and none are allowed to leave.

Under pressure from the UN Human Rights Council to stop sending Rohingya to the island against their will, the Bangladeshi authorities are now engaging in an all out marketing campaign to promote the island as a spacious and modern alternative to the conditions faced by those living in the camps.

Their efforts include taking a small pool of journalists, including the BBC, on an exclusive media tour of the facilities, all coordinated by and under the watchful eye of the Navy and intelligence service.

After three hours' travel aboard a Navy vessel, the small band of journalists were met by Commodore Abdullah al Mamum Chowdhury before being escorted around the newly finished site.

Commodore Chowdhury briefs journalists about the possibility of storms close to the island

The newly built town forms a giant grid, with hundreds of rows of red roofed houses. All that we saw stood vacant, waiting for an influx of refugees. Overhead, installed on every house and every corner, security cameras kept watch.

Navy officials were keen to point out two schools, a mosque, two 40-bed hospitals and two community clinics, all currently under construction.

"The infrastructure is eco-friendly," said Chowdhury. "There is plenty of open space. Here they will have electricity which they don't have in Cox's Bazar camp. The most important thing is education. We have constructed schools for Rohingya children where they will get better education."

The newly built town forms a giant grid on Bhasan Char

Earlier this year, Amnesty International released a damning report, external on the conditions faced by the 306 Rohingya already living on the island. The report contained allegations of cramped and unhygienic living conditions, limited food and healthcare facilities, a lack of phones in order for refugees to be able to contact their families, as well as cases of sexual harassment by both the Navy and local labourers engaging in extortion.

Chowdry denied the allegations. "We are taking care of them as our guests," he said. "They are given proper food and access to all facilities."

When Chowdry was asked about the whereabouts of the 306 Rohingya already on the island, he said none was available to meet the gathered journalists.

Cattle rancher Tajul Haq

As the tour continued beyond the vacant buildings and out into the fields, some signs of life emerged from the swathes of green grass.

Hundreds of buffalo and sheep stood grazing, and watching over them was 50-year-old cattle rancher Tajul Haq, who said he had been working on the island for the past five years, caring for the buffalo.

"I look after around 100 buffalo on behalf of the owner. The island is full of grass so suitable for buffalo. The land is also very fertile. You can grow anything," said Haq.

The Bangladeshi government has long-promised the UN access to the island in order to carry out an official assessment of the long term safety and sustainability of Bhasan Char. But the Bangladeshi authorities are still holding the UN at bay, leaving the question of whether the land can provide enough food, facilities and livelihood opportunities to support 100,000 people unanswered.

The UN High Commissioner for Refugees told the BBC that, with the arrival of 306 refugees, an onsite visit by the UN was now even more crucial to assess the conditions for those already living on the island. They said they had submitted their request to the government, but were yet to hear back.

Members of the Navy showed journalists around the island's edible garden

Many Rohingya are also concerned that the island, at just 6ft above sea-level, is extremely vulnerable to cyclones, monsoon rains and tidal surges.

Commodore Chowdury said during a power-point presentation to journalists that not only had a 14km long seawall been constructed to protect the island, but that "experts" had established the risk of the island being hit by a cyclone as "very low".

"No severe cyclone-eye has hit this area in the last 172 years," Chowdury said. He showed off what he said was 120 cyclone shelters capable of withstanding 260kph winds.

But contrary to Chowdury's claim, there is evidence, external to suggest two cyclones did in fact track right across or very close to Bhasan Char in 1991 and 1997. And it is well documented the damage caused by cyclones frequently occurs many miles from the eye of a storm.

Bangladesh experiences an average of more than one cyclonic storm every year, and the BBC's own internal weather experts said the likelihood of Bhasan Char being affected in the future was high, and that the topography and low-lying ground meant such storms could cause major flooding both from excessive rainfall and coastal storm surges.

The island is believed to have been formed from Himalayan silt

A house is not always a home

The isolation of Bhasan Char is also something the Rohingya fear. Back aboard the Navy vessel after the commodore's tour, it was another three-hour rough ride back to the mainland.

"The houses are good in Bhasan Char, but it looks like a prison," said Nur Hossain, a Rohingya camp resident who had seen pictures of the island, and spoken to Rohingya elders who visited.

"In Cox Bazar we are living as a community," he said. "But on the island, our freedom would be restricted. We would have to live under Navy surveillance."

Children flying kites in a camp in Cox's Bazar, where most of those who fled Myanmar now live

For others in the camps, living so close to the border between Bangladesh and their homeland of Myanmar offers some solace. And the option of moving to a remote island feels like a shift even further away from their dreams of returning home.

One community elder who was among 40 or so taken on a tour of the island in September, but who asked not to be identified for fear of retribution, explained the importance of the camps being close to the border with Myanmar.

"The Bangladesh government wants us [the elders] to speak publicly in the camps in favour of the island. However, the general population brand us traitors if we speak for relocation," he said.

"They are dead against the plans to relocation to the island. It doesn't matter how beautiful the infrastructure is, Rohingya feel connected to their roots in Myanmar while staying in Cox's Bazar."

Bathed in evening sun, construction workers walk past the island's lighthouse

Even for Khatun, the idea of leaving the camps to be reunited with her children is too much of a risk. Because for her, the camps were always temporary, and three years on her aim is still for all of her family to return to Myanmar.

"I want my son and daughter back here," she said. "Why should I go there? Here, Myanmar is close. If we get justice, we shall go back to Myanmar as soon as possible. I'll not go to Bhasan Char."

Photographs: Salman Saeed and Akbar Hossain. Producer: Claire Press

Related topics

- Published23 January 2020

- Published29 May 2020

- Published16 April 2020