The judge who stood up to Pakistan's military

- Published

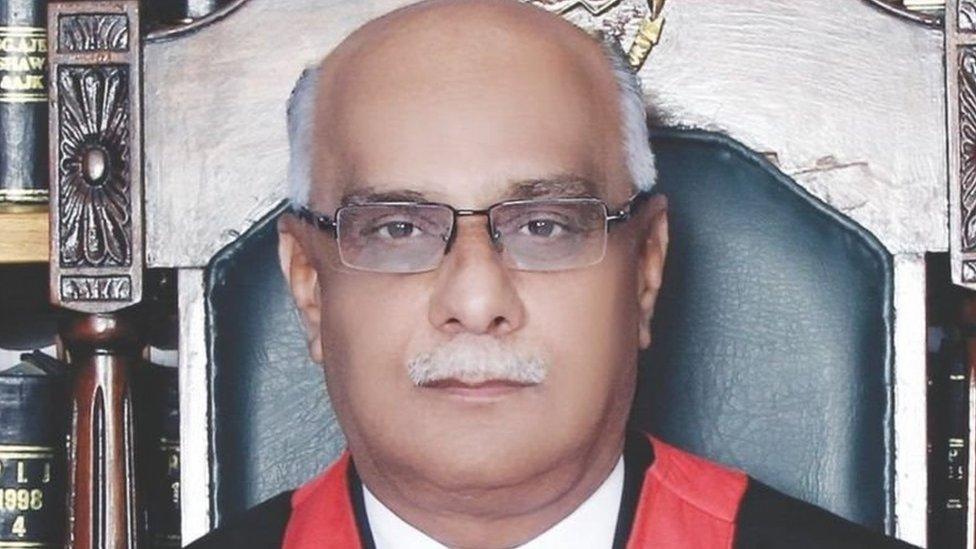

Justice Seth, seen here in hospital days before he died

Justice Waqar Ahmad Seth, who has died after contracting coronavirus, was an outspoken judge of a kind rarely seen in Pakistan and an unlikely source of opposition to the powerful military.

Tributes described him as bold, fearless and independent. He was 59.

As chief justice of Peshawar High Court (PHC), he passed judgments that angered both the military and the government - including a death sentence on exiled former ruler General Pervez Musharraf that made headlines around the world.

He also challenged the establishment on human rights abuses, striking down a law under which the military ran secret internment centres, and acquitting dozens of people convicted under anti-terrorism laws for lack of evidence.

Justice Seth's death is being seen as a major setback in a country where the military has been expanding its influence again in recent years.

Lawyers around the country have been in mourning since his death in an Islamabad hospital on 13 November.

Waqar Seth became chief justice in Peshawar 2018 but was not promoted to the Supreme Court

The secretary-general of the independent Human Rights Commission of Pakistan (HRCP), Harris Khalique, called his death a "great blow to a judiciary struggling to be independent in Pakistan's quasi democracy".

Mr Khalique told the BBC that Justice Seth represented the tradition of "conscientious and fearless judges… who unfortunately always remained in a minority".

Former senator Afrasiab Khatak said in a tweet that Justice Seth's stature was raised not just by the list of his remarkable judgments, "but also the oppressive conditions that required courage for writing such judgments".

Supreme Court Bar Association president Abdul Latif Afridi described him as "a courageous and uncompromising" person who didn't shy away from a fight with the military.

"And he paid a personal price," Mr Afridi told Dawn newspaper, recalling that the Peshawar chief justice had been denied elevation to the Supreme Court three times despite his seniority.

Rulings that rocked the military

Justice Seth made history when the three-member special court he headed sentenced Gen Musharraf to death last year in absentia. The general had been found guilty of treason for suspending the constitution and imposing emergency rule in 2007.

News of the Musharraf sentence in December 2019 sparked protests

It was the first time the treason clause in the constitution been applied to anyone, far less to a top military official by a civil court in a country where the military has controlled political decision-making for most of the time since its independence from British rule in 1947.

The penalty was unlikely to be carried out. Gen Musharraf, who has always denied any wrongdoing, had been allowed to leave Pakistan in 2016 on medical grounds.

The ruling allowed for this, saying if he died before he could be executed his corpse should be dragged outside parliament in Islamabad and "hanged for three days".

There was outrage, with the government seeking to disbar Justice Seth for being unfit for office, and legal experts calling the instructions unconstitutional.

Unsurprisingly, the ruling also touched a raw nerve with the military, which issued a rare statement saying the verdict was "received with a lot of pain and anguish by the rank and file" of the armed forces, and that Gen Musharraf "can surely never be a traitor".

The power and influence of the Pakistani army

Commenting on the ruling, the HRCP's Harris Khalique said that while some might have disagreed with Justice Seth's choice of words, "his very act of convicting a martial ruler for treason in accordance with the spirit of the constitution was a historic feat".

The judgement is still being challenged through the courts.

The Musharraf sentence was not the only time Justice Seth issued a ruling that displeased the military. Soon after taking charge as chief justice in Peshawar in June 2018, he acquitted more than 200 civilians convicted in secret trials by military courts that had been constituted following the December 2014 massacre by the Pakistan Taliban at Peshawar's Army Public School.

He cited a lack of evidence and "malice in facts and law" as grounds for those acquittals.

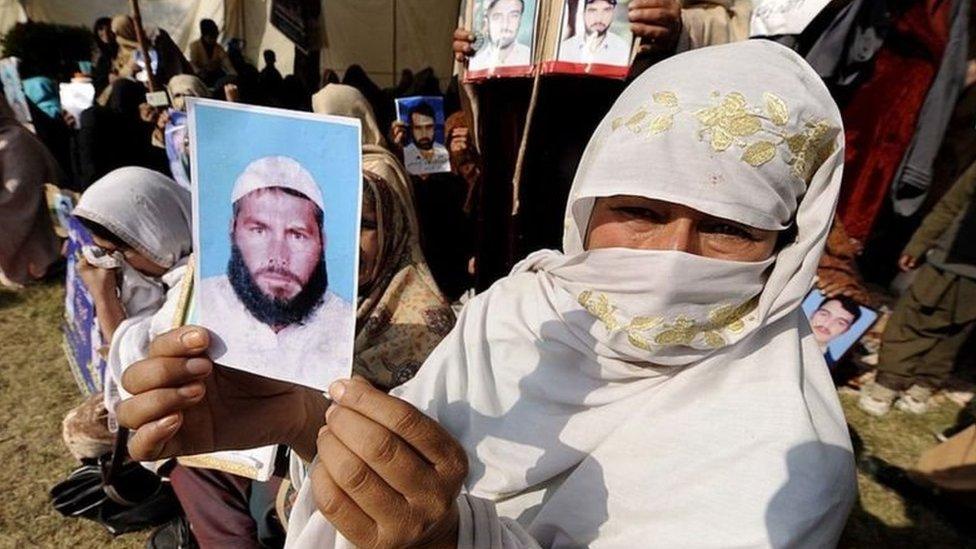

In October last year, he struck down a discreetly promulgated law in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP) province which had empowered the military to run secret internment centres to detain civilians indefinitely without judicial or administrative oversight.

"The acquittal of military court convicts last year had riled some quarters in the garrison, but when he struck down the law on internment centres, it became clear to most that Justice Seth was fearless and curried no favours with the power centres," said Wasim Ahmad Shah, a senior legal affairs correspondent for Dawn newspaper in Peshawar.

"Later, when he was appointed to head the three-member special court to try General Musharraf in what was seen by many as an open-and-shut case, most people knew what to expect."

Legal 'nit-picker'

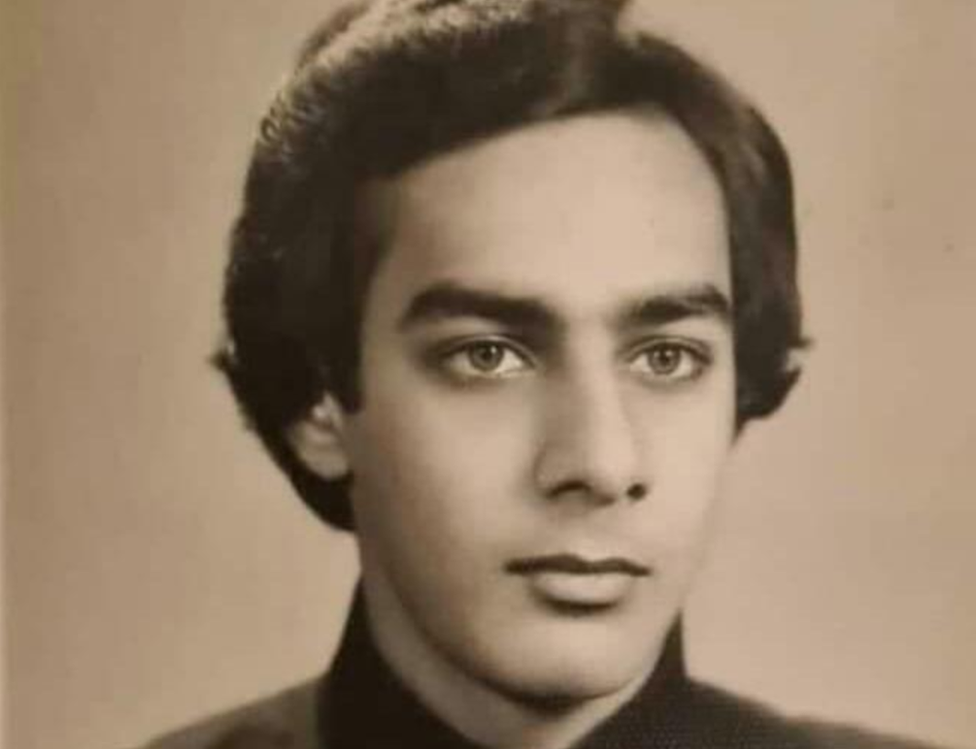

Waqar Ahmad Seth was born on 16 March 1961 into a middle class family in the city of Dera Ismail Khan in the south of what was then North West Frontier Province (later KP). He received most of his education in Peshawar, graduating in law and political science in 1985. The same year he enrolled as a practising attorney.

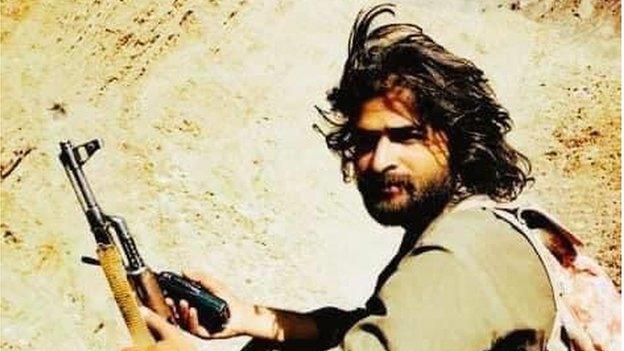

Waqar Seth pictured in the early 1980s when he was a student in Peshawar

Lawyers who knew him said he was a socialist at heart. He was active in the student wing of the left-leaning Pakistan People's Party (PPP) and later hung portraits of Karl Marx, Vladimir Lenin and Leon Trotsky in his private law office.

"But he kept a low profile and was never active in politics of the PHC bar, which many use as a platform to extend personal influence," says Shahnawaz Khan, a Peshawar-based lawyer who was close to him.

"Instead, he focused on details of the court cases he took up for pleading, often refusing cases he considered inconsequential, unlike most other lawyers who would take up any case irrespective of its merits, as long as the litigant could pay his or her fees."

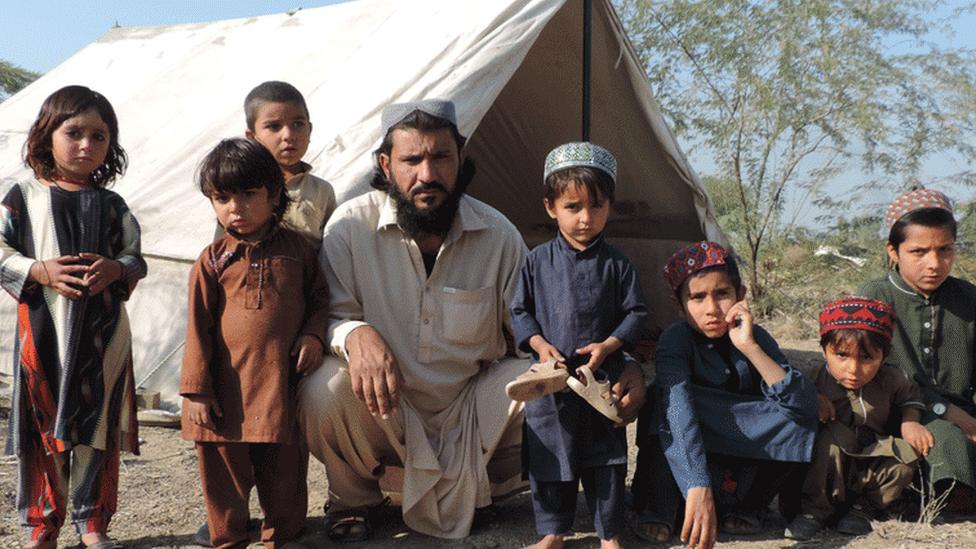

Relatives of people detained by the military had reason to thank Justice Seth

Justice Seth is remembered as a lawyer who waived his fees if he felt a case was deserving.

In his verdicts he had a tendency for legal "nit-picking".

The International Court of Justice (ICJ) in its briefing paper on Pakistan's military courts, released in January 2019, admitted this much when it mentioned that while petitions of people convicted by military courts had been rejected by the Pakistani Supreme Court in 2016 for lack of jurisdiction, the outcome was different when the same petitioners approached Justice Seth's high court in 2018.

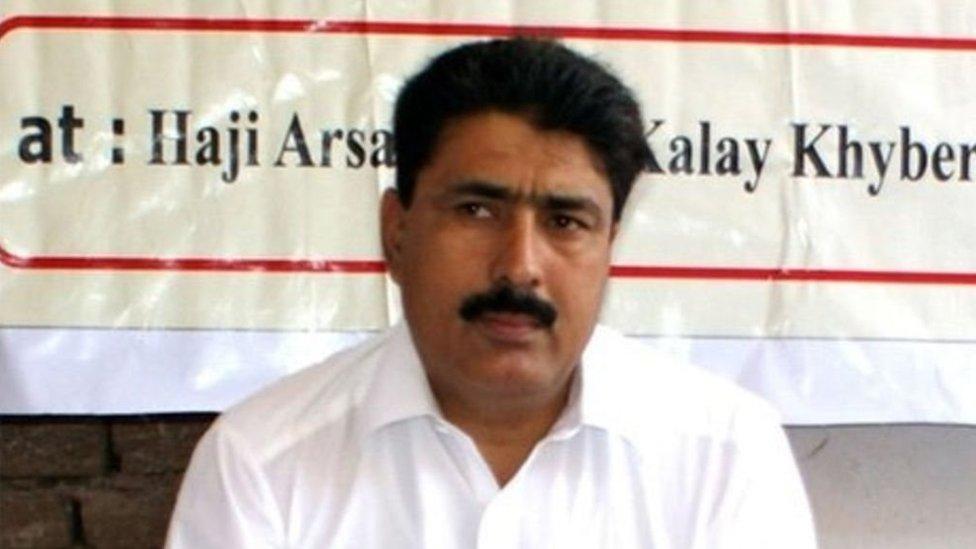

Many thought he might further rock the establishment by acquitting on appeal the so-called "Bin Laden doctor", Shakil Afridi, who helped the US find the world's most-wanted man, who had been hiding on Pakistani soil.

Pakistan was greatly embarrassed by the US air raid that killed Bin Laden deep inside its territory, and many believe Dr Afridi, who was accused of treason, became a scapegoat.

Observers say Shakil Afridi might have been acquitted by Justice Seth

Dr Afridi was never formally charged for his role in the 2011 operation to kill the al-Qaeda leader, and instead was convicted on other charges. He argues he was denied a fair trial.

But, "with Justice Seth gone, he has little hope of freedom left unless another judge with an addiction for his job rather than personal interest hits the scene", said journalist Wasim Ahmad Shah.

'Like a common man'

Many thought Justice Seth's rulings might put him at risk - few could have foreseen that it would be the coronavirus that would end his life.

His ruling in the Musharraf treason case sparked a hate campaign against him by elements that seemed to have the support of the authorities.

Given his habit of shunning "the grand security protocols other senior officials crave, we often feared he was putting his life in danger", said lawyer Shahnawaz Khan.

"He always used his personal car to drive to work and back, and could often be seen in the market doing shopping with his family, or sipping tea at a cafe with an old friend, just like a common man."

- Published24 July 2020

- Published31 July 2020

- Published13 January 2020

- Published17 December 2019

- Published2 June 2019

- Published13 January 2020