Kaavan, the world's loneliest elephant, is finally going free

- Published

Kaavan with a caretaker in his enclosure at Marghazar Zoo in June 2016

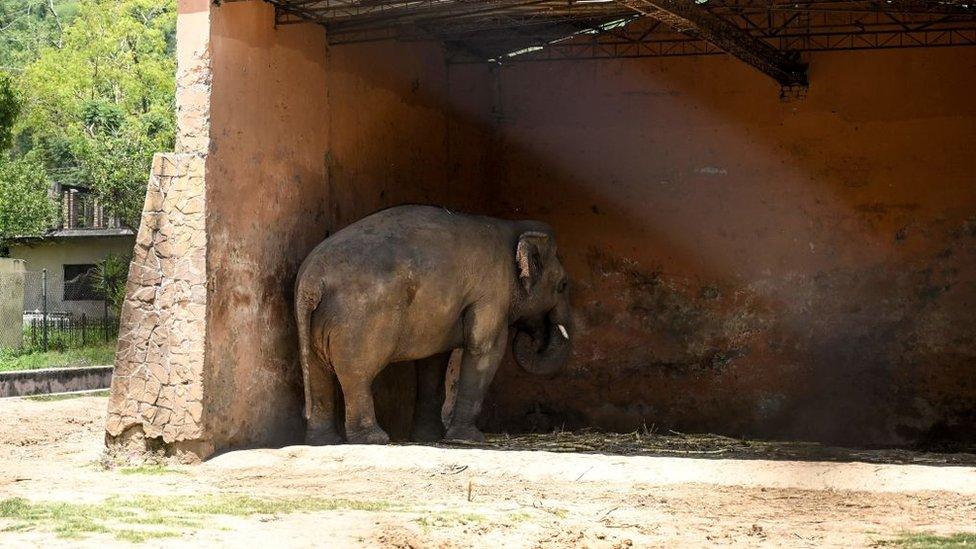

For decades, the world's loneliest elephant has entertained crowds from his small, barren patch of land in a Pakistani zoo.

The visitors would call for more as he saluted them, prompted by handlers who poked him with nailed bull hooks to make him perform for the money which lined their pockets.

Around him, animals disappeared from their enclosures, rumoured to be bound for the plates of the wealthy, while his only companion died, allegedly of sepsis brought on by those bull-hook nails digging deep into her skin.

And for years, it seemed that no one cared about the elephant's lonely fate. His wounds became infected and the chains around his legs slowly left permanent scars. He drifted slowly into psychosis and obesity.

Kaavan standing under the cover of a shed in his enclosure

But on Sunday, the world's loneliest elephant will finally leave behind his desolate enclosure for a new life on the other side of the continent, thanks to the determination of a coalition of determined volunteers and, somewhat unexpectedly, the American pop icon Cher.

This is the story of Kaavan. It begins with a prayer and ends in a song.

The prayer

Kaavan may never have ended up in Pakistan had it not been for a Bollywood film, some delicate international diplomacy, and the whims of one little girl.

Zain Zia, the daughter of Pakistan's then-military ruler Gen Ziaul Haq, fell in love with elephants after watching Haathi Mere Saathi (Elephants my Friends).

And so, she uttered a prayer.

Young Zain Zia with her father, General Haq

"I looked up at the sky and prayed, Allah Mian, give me a haathi mera saathi (dear God, give me an elephant to be my friend)," Zain told the BBC recently.

Her prayer was heard - by her father. One morning not long afterwards, as Zain was getting ready for school, Gen Haq asked her to stop, blindfolded her, and led her out into the back lawn.

"He said there was a surprise for me," she recalled. "He made me touch it. Then he removed my blindfolds, and there the little elephant stood. He was so lovely. I insisted we'll keep him at home, but my father said he belonged to the government and must go to the zoo. He said we won't be able to take good care of him, especially when he grew up. So then I said OK."

Zain Zia at her home in Pakistan

The little elephant was Kaavan, who had - until that day - been kept at Sri Lanka's Pinnawala Elephant Orphanage (PEO), according to Ravi Corea, a US-based Sri Lankan elephant rehabilitation expert. It is thought the year-old calf had been gifted to Gen Haq's government as thanks for backing the Sri Lankan army during an insurgency.

The exact reasons remain murky - as does the question of whether Kaavan was really an orphan - but we know that at some point in 1985, the young elephant ended up at a zoo in Islamabad.

A goldmine

Marghuzar Zoo had been built just seven years earlier, but already a power vacuum had emerged at the top, into which a number of "business mafias" had stepped.

Put simply, the authorities did not seem to care what happened at the zoo, or to its animals.

And so, a number of influential zoo employees began offering contracts to family members, allowing them to run food stalls and children's play areas within the attraction's grounds, as well as on the surrounding green belts.

A boy swinging on elephant statue in the avenue outside Islamabad zoo

They had other ways of making money too.

There is evidence to suggest that animals, mainly black bucks, had been surreptitiously supplied to drinks-and-barbecue parties hosted by influential people in the region at various times.

When a group of volunteers called the Friends of Islamabad Zoo (FIZ) started to hold periodic surveys at the zoo in 2019, they found the animal numbers had fluctuated. When they pointed out these anomalies, new animals suddenly appeared in enclosures.

That was not the only thing the group discovered.

"There is no veterinary facility, and no medicine supplies in the zoo," Mohammad bin Naveed, a FIZ volunteer, says. "There's no animal health facility here; there is no room where a surgery can be performed, and no space where a sick animal can be kept in isolation."

In the midst of all this was Kaavan, the zoo's star.

Zoochosis

Kaavan's job was to stand at the fence to entertain the crowds during opening hours, raise his trunk as a begging bowl when his mahout, or handler, prodded him with a bull hook, passing him the money the crowd gave him.

Visitors to Marghazar Zoo gather around Kaavan on the Eid holidays in July 2016

Kaavan's nights were spent idling around his small half-acre enclosure, about the same size as half a football pitch and containing a hut with concrete floor. When volunteers from Four Paws International (FPI) animal rights group compiled a report later, they found "a dry moat with narrow concrete walls; compacted soil; no other natural loose substrate, no trees, logs, bushes, rocks, tires or any other structures".

But at least Kaavan was not lonely. For years, his constant companion was Saheli, an Urdu word for a 'female friend' - an elephant brought in from Bangladesh in early 1990s.

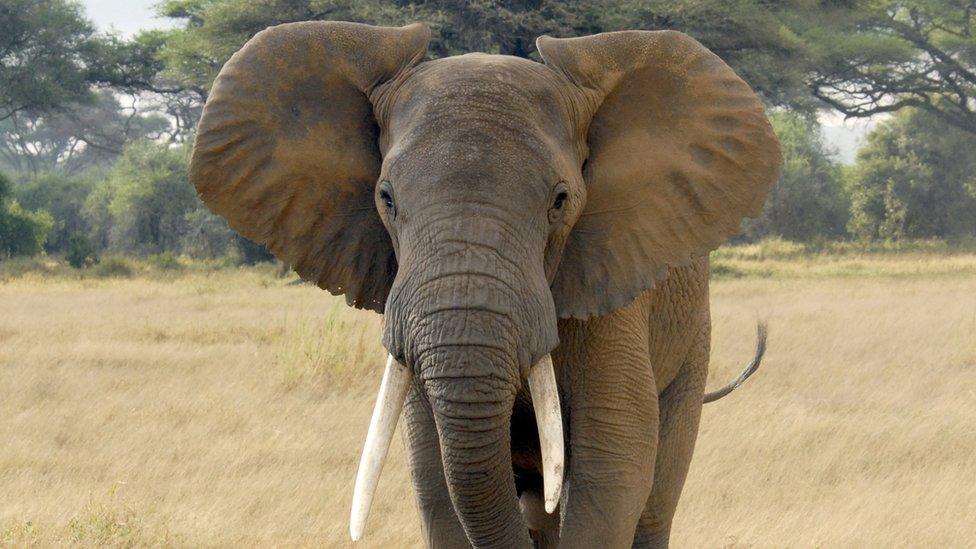

The need for such companionship should not be underestimated. Wildlife experts say elephants are cognitively sophisticated and sentient, almost like humans. They have nearly the same life span - between 60 to 70 years in the wild - and have similar emotions, forming strong family bonds.

They also mourn their dead.

Saheli died in 2012. The official version of events is that she died of a heart attack due to the hot weather, but Mohammad bin Naveed, the a FIZ volunteer, alleges it was actually sepsis.

"At some point the unsterilised nails of the mahout's bull hook went too far into her skin. She got gangrene and died of a septic shock. Everyone knows this, but won't admit it," he says.

Kavaan shows his trunk in his enclosure at the zoo

Kaavan - already bereft of the natural environment he needed - had been acting increasingly aggressively in the years leading up to her death. He spent prolonged periods in chains from 2000.

After she died, he got worse. His mahout warned that he was dangerous and allowed no one, including himself, to get close to the lonely elephant.

By the time the team from FPI arrived in 2016, they found an "aggressive" animal suffering from "zoochosis". He had "low locomotive activity, no explorative or comfort behaviour, advanced stage of stereotypical behaviour (constant bobbing of head)" and complete indifference to humans, "except some begging".

His physical condition was also deteriorating, FPI said, finding "mild conjunctivitis in left eye, some less pigmented areas on lower legs indicating old chain lesions, several cracked nails and overgrown cuticles".

Kaavan was sick, that much was clear. He was also worryingly overweight, a result of the high sugar diet his keepers fed him.

But no one wanted to lose the zoo's star attraction. What Kaavan needed, it turned out, was an even bigger star to come to his aid.

The song

Cher first learned of Kaavan's plight in 2016. The Oscar-winning actress and singer, who cofounded Free the Wild, a wildlife protection charity, hired a legal team to press for the elephant's freedom.

When the court order freeing him was announced in May, the singer called it one of the "greatest moments" of her life. In the months since, she has chronicled his progress on her Twitter account, where she has 3.8 million followers.

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

But the fight for Kaavan and the other animals in the zoo was not over. The problem was tossed from one department to another, before finally ending up in Islamabad's High Court.

In June, the order came to close the zoo for good. But Kaavan's fate remained uncertain.

There were those, Mohammad bin Naveed says, that took the "egotistical route" saying they would refuse to let Kaavan go abroad, "that they would take care of him".

But as the World Wildlife Fund's Dr Uzma Khan pointed out in a recent television interview, Kazaan's zoo was the not the only one with problems. Pakistan doesn't have uniform standards when it comes to keeping animals. None of its zoos is a member of the World Association of Zoos and Aquariums (WAZA).

Dr Amir Khalil, head of the FPI team, assists in bathing Kaavan in his enclosure

So Four Paws International was invited to the country a second time and a new plan was hatched - to fly Kaavan across Asia to Cambodia, where he could live out the rest of his years in a "protected contact" sanctuary.

There was only one problem. Kaavan was an angry 30-something elephant with a weight problem. Neither the anger nor the weight leant itself to an easy journey to Cambodia.

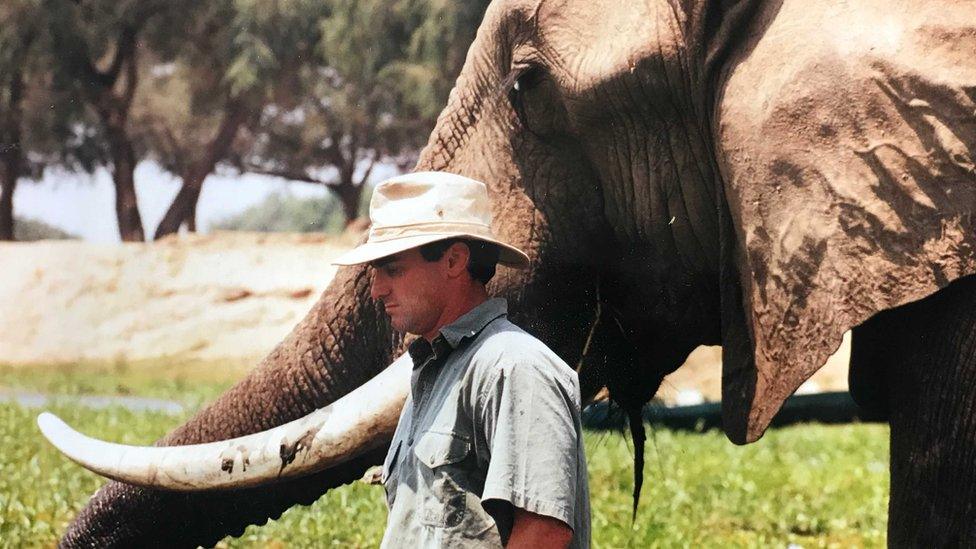

In the end, Dr Amir Khalil, the Egypt-born head of the FPI team, stumbled his way into a solution.

The team needed to make security arrangements so they could safely assess Kaavan's physical health, which meant Dr Khalil and a colleague had to keep the elephant in another part of the pen, requiring them to stand around for hours waiting.

It was, he says, a boring job.

"So I started to sing. And after sometime, I noticed that the elephant started to get an interest in my voice, which no-one loved anyway, so I was embarrassed. But then I was happy to have found a big fan, and I started to sing to him."

Soon Kaavan could be seen eating out of Dr Khalil's hands, hugging him with his trunk as he took a bath at the pond while his new friend sang along one of his favourite songs from the traditional pop era being played on a portable sound system.

Dr Khalil feeds Kaavan in a transport crate to prepare him for the journey to Cambodia

Not long after, this once-aggressive elephant happily followed Dr Khalil and his colleagues into the crate which had been specially designed to carry his five-and-a-half tonne weight on an eight-hour flight to Cambodia.

And on Sunday, after 35 years suffering at the hands of what Dr Khalil describes as a combination of "wrong management, lack of experienced staff, humanity mixing with business and money, and less attention to the welfare of animals", Kaavan will be taking flight.

Cher has hinted on Twitter since Kaavan's freedom was ordered in May that she might travel to Cambodia, and on Friday she landed in Pakistan on her way. Her exact schedule has been kept secret for security reasons, but she reportedly met with the prime minister, Imran Khan, on Friday.

She is expected to travel on from Pakistan to Kaavan's new home in Cambodia, the one-million acre Kulen-Promtep Wildlife Sanctuary, where volunteers and staff work to protect the natural habitant and house a wide range of endangered species.

Kaavan may still have problems overcoming his psychological issues and adjusting to a natural environment, his friend Dr Khalil says, but he "finally has a chance to be an elephant, and to live in a place he can call home".

Kaavan enters his crate, ahead of the long journey to Cambodia

- Published7 September 2020

- Published1 July 2020

- Published18 October 2020